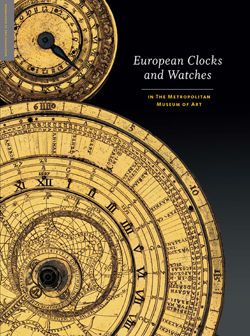

Mirror clock

Movement attributed to Master CR

Stem and foot probably cast from designs by Matthias Zündt German

Band of case from design by Cornelis Bos Netherlandish

Timekeeping has been associated with astronomical events from the earliest civilizations. Horologists and historians of science have long debated the question of whether the mechanical clock is a direct descendant of the late-medieval instruments that were invented to demonstrate the apparent motions of the heavens, or whether the invention of the mechanical escapement for use in a clock subsequently permitted the construction of a mechanically driven astronomical device.[1] It has not been satisfactorily resolved even as yet.

The large circular dial of the Metropolitan Museum’s clock exemplifies the close connection between timekeeping and astronomy during late-Renaissance Germany. Incorporated into Renaissance clocks, as it appears in the center of the dial of this clock, the astrolabe represents the stellar sky. The device employs one or more tympans (or circular plates) that are engraved with flat projections of terrestrial latitudes and longitudes, which form the grid for a map of the stars from the horizon to the zenith as seen from a given latitude on earth. The revolving rete is mounted on top of the tympan, and its components consist of the circle of the zodiac and an openwork design that incorporates flame-like pointers, which represent the relative positions of the brightest stars.

This variety of astrolabe exists as two types. One type is the ordinary, manually adjustable instrument that is used for locating the positions of the brightest stars at any moment in time: past, present, and future. The second type is driven by clockwork and, when incorporated into a clock and properly adjusted, demonstrates the positions and the apparent motion of stars to be seen at a specific time from the latitude for which the clock was intended to be used. Unlike the manually adjusted instruments, the mechanically driven astrolabes were usually furnished with two concentric hands: one for the sun, which tells the time of day, and the other for the moon; together, they show the place of the sun and the moon in the zodiac circle. The hand for the moon is missing on the Museum’s clock, but the hand for the sun still exists, and the images of the moon’s phases are visible and would have been seen through an aperture in the moon’s hand. Visible, too, is the ring marked 1–29+ along the edge of the hand for the sun, which served to indicate the age of the moon in its monthly cycle. The tympan for the Museum’s clock is reversible and can be used for 40 degrees latitude on one side and 50 degrees latitude on the other, and there are twenty-three stars that appear on the rete with their names and pointers.

The second most visible feature of the dial is the revolving calendar ring that indicates the months, each day of the month, the Dominical Letters, and the Saints’ Days with six months to a side and beginning with Aries marked on the eleventh of March. The calendar ring and the astrolabe are held in place by a ring with bayonet fittings that are spring held on the reverse, which serves as the chapter ring for the hours (I–XII, twice), as well as rings that are marked with the numerals of the twenty-eight-year solar cycle, including the Dominical Letters for the years beginning in 1570 and ending in 1610.[2] These concentric rings are framed by a thin band at the outer rim of the ring that now registers minutes and quarter hours. Most likely, the ring originally registered only five-minute intervals and quarters, for which it is marked 5–60 and I–IIII. The numerals on the hour chapter are augmented by touch pins for using the clock in darkness.

Here, the Museum’s clock functions as a drum clock, but it is turned on its side and supported by an elaborately decorated stem and an openwork foot. The foot originally contained a bell upon which a hammer in the clock would have struck the hours. A second drum-shaped unit is attached to the top of the clock, and it contains an alarm mechanism with a second bell (now missing), which also served as the bell for the quarter striking of the clock. The movement consists of two circular iron plates that are held apart by four cylindrical iron pillars. The movement contains a going train and two striking trains of iron wheels, originally laid out for twelve- and twenty-four-hour striking. The trains are driven by open springs, and parts of the original stackfreed regulation remain.

This type of clock was once called a monstrance clock because its form resembled that of the container for displaying the Consecrated Host. It is certain from the references in the Augsburg guild specifications for masterpiece clocks, however, that as early as the first clocks of this description were being made in Germany, they were called mirror clocks (Spiegeluhren), presumably as a result of their likeness to a lady’s mirror. Soon after, a “clocke made lookinge glassewise,” presumably referring to a similar type of clock, was listed in the will of the clockmaker Nicholas Vallin from London (active ca. 1565–1603),[3] whose exquisite watch in the form of a Lesser George made for a member of the Order of the Garter (the highest order of the English knighthood) appears elsewhere in this survey [see 17.190.1475].

It is not the form of the Museum’s clock but the ornament that places its maker in late-Renaissance Germany, and Nürnberg, in particular. The hollow stem of the case is covered with a distinctive variety of ornament called grotesque, because of its origins in antique Roman wall decorations discovered in Italy during the late fifteenth century and buried underground or in grottos: hence grotesque. Here, the elements of grotesque ornament (hybrid human and animal figures, satyrs, fruits, and masks) are piled one next to another in a sort of high relief (horror vacui). The same kind of overloading of ornament can be found in a group of designs for jewelry and weaponry published in Nürnberg in 1553 by the goldsmith and etcher Matthias Zündt (ca. 1498–1572).[4] Zündt is recognized as a journeyman in the workshop of his father-in-law Wenzel Jamnitzer (1508–1585), who was probably the most famous goldsmith in sixteenth-century Nürnberg. By 1560 Zündt had also become a master goldsmith in Nürnberg,[5] and records show he was a stone carver at the same time. According to John Hayward, there are four carved models for casting the sides of cases for table clocks that have been attributed to Zündt,[6] but these models are of pear wood and not stone. Hayward also found evidence that Zündt referred to himself as a wood-carver (Bildenschnitzer) in 1559, when he was working for the Habsburg Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria (1529–1595), perhaps a more likely occupation than stone carver for a future goldsmith.

The Zündt-derived clockcase found in the Museum’s collection has added supports for the heavy clock movement, which seem to have been directly borrowed from the gargoyles that inhabit a great deal of late-medieval architecture. The openwork base of the clock is made from a somewhat less florid design, but one is still less than eager to pick up the clock either by the stem or the base. The design of the base bears close comparison with those of earlier designs for drinking vessels attributed to Zündt and published in 1551 with the title Insigne ac Plane Novum Opus Cratero Graphicum.[7] Several of these vessels are embellished with freestanding figures of satyrs or partially human figures that are comparable to the ones found on the bottom of the stem and on the base of the Museum’s clock. The ornament that appears on the side (or band) of the clock, while adhering to the grotesque vocabulary, is somewhat less crowded and more restrained in the depth of its cast relief. This ornamentation is derived directly from an engraving believed to have appeared in 1550 by Cornelis Bos (ca. 1510–1556), the Dutch designer of grotesque ornament [8] and part of a series of prints combining such ornaments with three-dimensional strapwork.

From evidence provided by the regulations recorded in 1563, when clockmaking in Nürnberg ceased to be a free trade, candidates for admission to the newly created company of clockmakers were required not only to make the movement of the clock but also to design the case. These case-design patterns would then be carved in wood by a wood-carving specialist, thereby facilitating the models for eventual casting in metal. It is not certain that a master clockmaker was always expected to provide an original design for his clockcases. The regulations from 1563 show that the clockmaker and the wood-carver were separate individuals, and the former, not the latter, might expect to retain the wooden patterns as his property.

In addition, the Museum’s clock has been identified as one in a group of clocks made in Nürnberg during this time. Most of these clocks are signed by an as-yet-unidentified clockmaker with the initials “C.R.” [9] This group includes a so-called Metzger-type table clock now in the Museo Galileo/ Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Florence, [10] and a mirror clock now in the Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart.[11] The Museum’s clock is not signed, which is probably due to the fact that the cover for the back of the movement is a replacement of the original. Nürnberg clockmakers often signed their drum-shaped clocks on the bottom of the case in a location comparable to that of the missing cover for the back of the Museum’s clock, which may explain its lack of a punchmark or signature.

The clock has had an eventful, if not entirely happy, existence. A short pendulum with an anchor-shaped weight has been substituted for the original balance. Probably around the same time as this substitution, the clock was turned into a simple timepiece—all of the underdial motion work for the astrolabe and the calendar is now missing, as are the bells for both the hour- and quarter-striking mechanisms. The hand for the sun has been shortened, and the hand for the moon is missing, as is a pointer to mark the day on the revolving calendar and probably one for the solar cycle. The clock is likely to have had a later minute hand too. The disk for setting the alarm is a late replacement, and it has been immobilized with solder; the finial above the alarm is most likely even later in date. Finally, a large crack near the base of the stem has been repaired with little effort to disguise the work.

Nothing is known of the clock’s provenance before J. Pierpont Morgan acquired it. Yet it remains one of the earliest survivors of a type of clock that was in vogue in Germany for nearly a hundred years, and its case is a particularly exuberant example of a distinctive type of metalwork produced in Nürnberg in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] See Price 1955, pp. 810, 814; Landes 1983, pp. 53–58, 402–3, nn. 4–8. See also North 1975, pp. 383, 385; Turner 1985, pp. 1–10; J. Evans 1998, pp. 141–55.

[2] Leopold 1974, pp. 101–3. See also Vincent and Chandler 1969, pp. 381–82.

[3] Lloyd and Drover 1955, p. 111.

[4] See Warncke 1979, vol. 2, pp. 64–65, nos. 423–31.

[5] Martin Angerer in Wenzel Jamnitzer 1985, p. 372. See also J. C. Smith 1983, p. 270; O’Dell-Franke 1996.

[6] Hayward 1975, p. 67. The title of Hayward’s article is somewhat misleading as the models are without doubt intended for the sides of more than one clock. See also Leopold 2002, p. 524, n. 39.

[7] See Angerer in Wenzel Jamnitzer 1985, pp. 372 and 373, no. 372, with a discussion of the attribution to Zundt. See also Warncke 1979, vol. 2, p. 61, no. 388.

[8] Berliner and Egger 1981, vol. 1, p. 67, no. 636, and vol. 2, ill. no. 636.

[9] Leopold 2002, pp. 522, 524–25 and n. 38.

[10] Ibid., p. 522, and p. 521, fig. 21.

[11] Ibid., p. 525 and n. 41, and p. 523, fig. 23.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.