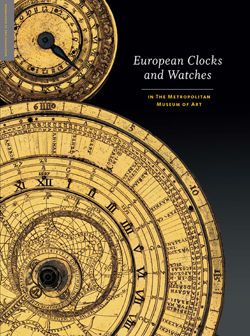

Watch with scenes from the story of Rebekah at the well

Watchmaker: Johannes van Ceulen Dutch

Painted enamel possibly by Henri Toutin French

Raised enamel possibly by I. Josias Belle French

Not on view

The second great seventeenth-century advance in timekeeping was the invention of the balance spring. When attached at one end to the balance staff of a spring-driven watch and attached at the other end to the back plate of the watch and set in motion, the oscillation of a spiral hair spring, like the swing of a pendulum, was discovered to be isochronous. Its employment increased the accuracy of a watch by an order of magnitude comparable to that achieved by the application of a pendulum to a clock. Both applications were the inventions of the Dutch mathematician, physicist, and astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695). Huygens’s immediate family included his father, Constantijn I Huygens (1596–1687), who was secretary to the Dutch head of state, Stadtholder William II (1626–1650); and his elder brother, Constantijn II Huygens (1628–1697), who was secretary to Prince William of Orange (later to become King William III of England and Scotland; 1650–1702). Consequently Christiaan Huygens had entrée to the highest circles in the courts of The Hague and London, as well as to the court of King Louis XIV (1638–1715) in France. His aristocratic connections, together with his scientific genius, insured him a ready welcome in 1663 as the first overseas fellow of the Royal Society in England and secured him a salaried position from 1665–81 in France’s Académie Royale des Sciences.[1]

Huygens’s early letters written in 1675 to Henry Oldenburg (ca. 1618–1677), the first secretary of the Royal Society, contain his first disclosure of the secret of the balance spring. The letters were quickly followed by a published description and diagram of the mechanism in the February 25, 1675, issue of the Académie Royale’s Le journal des scavans (later renamed Le journal des savants).[2]

The news unleashed a torrent of complaint in England about the priority of the invention from the Royal Society’s first Curator of Experiments, Robert Hooke (1635–1703), whose studies of the properties of springs were probably known to Huygens. In France, Huygens’s collaborator for the construction of models of the invention was Isaac II Thuret (1630–1706), who was probably the best of King Louis XIV’s clockmakers and also claimed to be the inventor of the mechanism.[3] In the end, Huygens never obtained a patent in England nor in France, thereby granting freedom to all to employ the invention.

As a result of the patent disputes, Johannes van Ceulen the Elder (active 1675–1715) became one of the first Dutch watchmakers to retain the right to make Huygens’s balance springs. While little is known of Van Ceulen before 1675, two years later, he had moved to an address on the Plein, the prestigious square in The Hague where the Huygens family also had a residence.[4] By that time Van Ceulen had already received a commission for one of the new balance-spring watches from Huygens’s brother Constantijn. The commission of the watch is mentioned in a letter from Constantijn to his wife (1676) while he was on military duty with Prince William on the French border, and receipt of the watch is recorded in his journal on July 18, 1676.[5] In 1688 Van Ceulen would become one of the founding members of the Clockmakers’ Guild in The Hague,[6] and he is known to have been the maker of a large number of spring-driven clocks regulated by Huygens’s short pendulums,[7] a type commonly known as a Hague clock (Haagse Klok).

The Metropolitan Museum’s watch is of the variety that Van Ceulen was making in 1676, which incorporated the new balance spring. In the felicitously designed layout of its back plate the hair spring is barely visible underneath the balance bridge. The bridge, with its tripartite openwork of delicately scrolling vegetation that radiates from a central rosette, is screwed to the back plate through two openwork feet, and it occupies the greater part of the plate with only a silver figure plate (marked 5–30 by fives) for adjusting the spring. The engraved signature of the watchmaker, “Johannes Van Ceulen Fecit Hagae,” completes the design. (Hidden between the mainspring barrel and the pillar plate of the watch is a wormand- wheel regulator for setting up the mainspring.)

The movement consists of two thin, circular plates of gilded brass, which are held apart by four Egyptian-style pillars with pierced ornaments at their top ends, and a train of three gilded-brass wheels that end in a verge escapement with a balance wheel of three arms regulated by the newly invented hair spring. The fusee has grooves for seven turns and a fine steel chain. The dial plate has four feet that are pinned to the top plate (or pillar plate) of the movement, and it supports a painted-enamel chapter ring for the hours (I–XII) with dotted ornaments marking the half hours. Around the hour chapter is a circle of matte gold with polished gold reserves that emphasize five-minute periods (numbered 5–60 by fives) in incised and blackened numerals. The inner edge of the circle displays the minutes in carefully calibrated lines. The center of the dial is painted enamel and depicts an antique architectural ruin with human figures in the foreground that has been adapted from an etching by Gabriel Pérelle (1604–1677), a prolific French artist whose landscapes were among those most often used as models by the seventeenth-century enamelers of Paris and Blois. The scene and the chapter ring for the hours closely resemble French enamel-cased watches of the mid-seventeenth century.

The rest of the watchcase is more problematic. The circular cover and basin-shaped case, as well as the dial and movement, are hinged together at the twelve o’clock position. The thickness and diameter of the case allow a confident attribution to a French enameler, but the question of the case was made is more difficult. Most seventeenth-century French enameled watchcases are shaped from a single sheet of gold so that the side (or band) of the case and the bottom of the case are one piece. The band and bottom of this case are two separate elements, which are joined together by a series of bent gold lugs that were disguised by cold enameling. The advantage of this construction is that it allows the joining of two separate kinds of enamel: painted enamel for the bottom, and raised enamel, or enamel in relief, on the band. These two types of enamels are often the products of separate craftsmen. The cover, too, consists of a painted-enamel plaque with an added gold frame, or bezel, of white enamel in relief, attached, like the band, by means of gold lugs that are bent to attach the bezel to the plaque. The origin of the landscape on the interior of the cover has not been identified, but the man with two impatient dogs who has stopped to chat with a friend may have been the invention of the enameler.

While seventeenth-century enameled watchcases have not survived in quantity and were probably never made in great numbers, watchcases constructed in the manner of the Museum’s Van Ceulen watch are remarkably rare. A watchcase cover in the collection of the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva [8] displays a scene of Elijah and Rebecca at the Well; this same scene is on the cover of the Metropolitan Museum’s watch, but the Geneva piece is painted in monochrome blue enamel. In addition, the cover has a bezel of raised enamel that is nearly identical to the Metropolitan’s Van Ceulen watchcover bezel, and it has been dated to about 1650 or 1655. Another watchcase constructed in the same way as the Van Ceulen watchcase is in the Metropolitan’s Robert Lehman Collection.[9] The interior side of the bottom of the case of the Lehman watch is enameled with the French Royal Arms; and the interior, or counter enamel, of the cover of the watch depicts King Louis XIV as a boy at the age of nine or ten on horseback, which lends support to a date of about 1645–48 for the watchcase. The movement, original to the case, is by Jacques Goullons (active 1626, died 1671), who is recorded working in Paris. Both objects tend to support a date of about 1650–55 for the Van Ceulen watchcase, but there is a further complication presented by the enamels.

The exterior of the cover of the Museum’s Van Ceulen watch has an exquisitely painted scene of Elijah and Rebecca at the Well, and on the back of the case there is another scene of Isaac and Rebecca; both scenes are illustrative of the Old Testament story in the Book of Genesis. The two scenes were apparently quite popular as they appear on a number of surviving watchcases.[10] Enamel expert Hans Boeckh has grouped the watchcase cover in the Patek Philippe Museum with eleven other watches with various subjects that he believes were either influenced by or directly copied from models by the French painter Sébastien Bourdon (1616– 1671).[11] No painting by Bourdon that could have served as a model for either scene of Rebecca has come to light, however, and there is some evidence that the model for Elijah and Rebecca at the Well might have been a painting not by Bourdon but by the Italian Filippo Lauri (1623–1694). Again, there is no trace of an original painting or even of a seventeenth-century print, the existence of which might be inferred from the number of enameled versions of the scene that survive. A reversed version of the scene does exist, however, in a print by engraver John Simon (ca. 1675–1751) (fig. 32),[12] a Huguenot from Normandy, who was employed for a time as a copyist by London printseller Edward Cooper (active 1682–1725), and succeeded him in the trade in 1723.[13] The print of Elijah and Rebecca has multiple identifications: “Abrahams Servant Presenteth Rebekah,” “Phil. Larvra pinx,” “I. Simon fec,” and “Sold by E. Cooper at ye 3 pigeons in Bedford street in Covent Garden.” At some point before 1723 Simon must have seen and copied either a painting or a print, and he may have misread the name of the artist.

None of the foregoing helps very much in dating the enamels on the Van Ceulen watch, although Boeckh has suggested that the scene on the Patek Philippe Museum’s fragment of Elijah and Rebecca is likely to have been enameled in Paris about 1650–55 by Henri Toutin (1614–1684). The convex band of raised enamel on the side of the case of the Van Ceulen watch is a mixture of strapwork and foliage that incorporates the type of occasional flower recorded in ornament prints by Daniel Marot (1661–1752).[14] These appeared in the early years of the eighteenth century, but reflected a style of ornament that was fashionable in his native France before Marot, a Protestant, left for the Netherlands in 1685 as the result of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes that same year. The band of the Van Ceulen watchcase, therefore, seems to belong to the 1680s rather than the 1650s, and its raised enamel is technically comparable to that found on the mounts for cameos made in the 1680s by the Parisian goldsmith Josias Belle (1624–1695). Belle’s jewelry for the French Royal Family has been identified by art historian Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, who also discovered a record of Belle as an embellisher of clocks with ornaments of various colored enamels.[15] One can only wonder whether enamel painting of the narrative variety that appears on the Museum’s Van Ceulen watchcase went on longer in France than is usually thought, or whether the watchcase was simply modified and brought up to date by a highly skilled Parisian enameler, possibly Belle, who was active about 1676– 80.

Taken together, the case is nearly as unusual as the movement, but some light may be shed on the problem of dating the watch by evidence that wealthy Dutch patrons were particularly enamored of watches with enameled gold cases and, with some notable exceptions, the enamelers of gold watchcases in the seventeenth century were either French or Swiss. The desired cases could be imported empty to be fitted with movements by Dutch watchmakers, as in the example of a watch by Pieter Klock (1665–1754) with a case by the Huauds of Geneva.[16] If it was especially treasured, a watchcase could be reused by a watchmaker who would supply a new and improved movement to fit the case, as was done with the Metropolitan Museum’s watch movement by the eighteenth-century Dutchman Lambertus Vrythoff (died 1769) in a case of about 1645 originally made for the French courtier Louis Hesselin (1602–1662).[17] The reuse of such watchcases can be explained as a result of a simple desire for a new movement incorporating the Huygens balance spring, an improvement in technology that made older pre–balance spring watches obsolete as timekeepers.

The condition of the movement of the Metropolitan’s Van Ceulen watch is excellent with the exception that the end of one pillar has been broken off. The center of the dial with the older markings for half hours may have been removed from an earlier watch, but the minute chapter ring was surely made to accommodate it, as well as to fit it to the case. The original hour hand and minute hand have been lost and replaced by a single hand by someone who could not have understood the significance of the chapter ring on the dial for minutes. The central loop of the hinge is missing. The enamels on the case show the expected signs of normal handling: areas of stress have lost much of their original enamel. The band of raised enamel has sustained numerous losses. The frame around the front of the cover, too, has many areas of enamel loss. These losses have been replaced by one of the Museum’s conservators. Many of the lugs that hold the frame to the cover of the case and the band (or side) of the case to the bottom have lost their enamel.

J. Pierpont Morgan acquired this watch from Carl H. Marfels of Frankfurt am Main and Berlin.[18] It was mentioned as being in Morgan’s collection as early as 1911.[19]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] For a fascinating account in English of Huygens, his family, and the society in which they flourished, see Jardine 2008;for his election to the Royal Society, see p. 309.

[2] Huygens (Christiaan) 1675. See Leopold 1993, pp. 41–42; Leopold 1996, pp. 107, 108, n. 63; Jardine 2008, pp. 266–68. See also Thompson 2008, p. 52, for a good description of the device. The text of Huygens’s publication of the invention in Le journal des sçavans is reproduced in Cardinal 1989, pp. 78–79, ill. no. 38, a–c. Robert Hooke’s unsuccessful attempts to apply balance springs to watches are discussed in 17.190.1512 in this volume.

[3] For an account in English of the dispute, see Cardinal 1989, p. 79.

[4] While most authors follow the biographical listing in Morpurgo 1970, pp. 25–26, more recent publications give Van Ceulen’s birth as “before 1657 . . . a descendant of a family of clockmakers probably originating from Maastrict” (Vehmeyer 2004, vol. 2, p. 997) or in 1656 (Peeters 2012, p. 305).

[5] Huygens (Constantijn) 1881, pp. 103, 114, quoting a manuscript in the Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen, Amsterdam. Both entries appear in translation in Jardine 2008, p. 263.

[6] For a reproduction of the charter of the guild in Jan. 1688, now in the Municipal Archives in The Hague, see Plomp 1979, p. 57.

[]7 For examples of Van Ceulen’s Hague clocks, see ibid., pp. 88–101.

[8] Inv. no. E 27. See Boeckh 2009, pp. 24–25 and figs. 17, 18.

[9] Acc. no. 1975.1.1244. See Vincent 2012, pp. 78–83, no. 21.

[10] They survive in various collections and include two more in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection (acc. nos. 17.190.1558 and 17.190.1565).

[11] Boeckh 2009, p. 25.

[12] The authors are indebted to Maxime Preaud, formerly of the Cabinet des Estampes, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris, for this discovery.

[13] On John Simon, see Clayton 1997, pp. 20–21.

[14] See, for example, Marot’s designs for ornament published in his Second livre d’orlogeries, reproduced in Ornamentwerk des Daniel Marot 1892, ill. no. 183, and in Oeuvre de Daniel Marot n.d., vol. 1, pl. 47. The date of the original publication of this

series is uncertain and opinions vary from about 1700 to about 1706. See Fuhring 2004, vol. 1, p. 375, no. 2224; see also Dee 1988, pp. 82–83.

[15] Bimbenet-Privat 2000, pp. 76–79; Bimbenet-Privat 2002, vol. 2, p. 501.

[16] See 17.190.1522 this volume.

[17] See Leopold and Vincent 1993.

[18] Williamson 1912, pp. 199–200, no. 222.

[19] Britten 1911, p. 760.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.