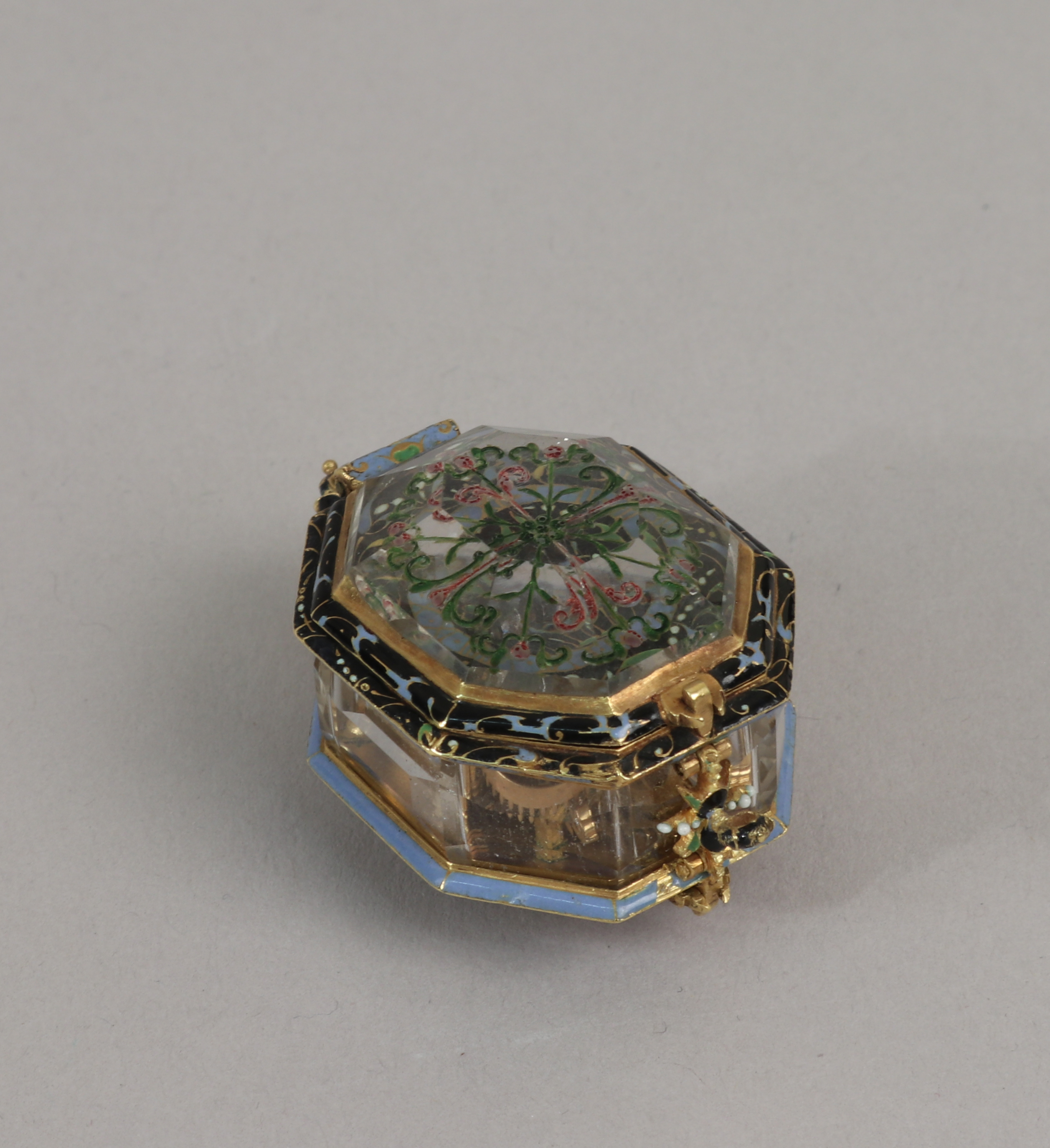

Watch

Watchmaker: Pierre Vernede

During the reign of King Louis XIII (1601–1643), a singular variety of ornament now known as cosses de pois (or peapod) became fashionable largely for the embellishment of jewelry but also for the enameled gold mounts of precious objects,[1] watchcases, and horse gear.[2] The origins of the style, as traced by art historians Peter Fuhring and Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, lie in the ornamental use of depictions of peapods split open to reveal rows of peas.[3] Found, for example, in a sixteenth-century German print by Hans Leinberger (active 1510–30), these rows were created in a somewhat analogous way to the bunches of grapes used by the better- known Albrecht Dürer as framing elements for some of his woodcuts.[4] Fuhring and Bimbenet-Privat also pointed out the similarities of certain leaf motifs found in the peapod style to those in the moresque ornament that was in vogue in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries throughout Western Europe.[5] By compiling numerous examples of ornament prints, for the most part by French and German artists, including some designs for black-and-white ornament, Fuhring and Bimbenet-Privat were able to document the increasing stylization of the pea and leaf motifs over the course of the first forty years of the seventeenth century.

It is among these prints that the sources of the three Metropolitan Museum watches with enameled gold and rock crystal cases can be established. All three watches have signed movements, but it is not certain who the casemakers were or where they might have been working. The dial plate for the Vernède watch displays the chains of graduated spheres, or “peas,” and the trifid-shaped leaf motifs that are characteristically found in the ornament prints, for example, in the two series of engravings published between 1618 and 1619 in Châteaudun, France, by Jean I Toutin (1578–1644). The medallion from the Toutin series supported by a lion above two human figures—one singing and the other inexplicably playing a gridiron with a pair of tongs as though it were a musical instrument— reveals a decorative vocabulary that is closest to that of the Vernède watch dial. An eight-sided watchcase depicted in Toutin’s Plate 4 compares closely in shape to the Museum’s watch (fig. 23).

The second watch in the Museum’s collection (fig. 24),[6] also in a rock crystal case, exhibits a far more abstract version of the peapod style. It has a movement signed “Noel Hubert à Gros Horloge a Rouen.” Noël Hubert (1612–1650), founder of a dynasty of watch- and clockmakers, was keeper of the fourteenth-century public clock in the city of Rouen, France. The dial of Hubert’s watch and the mounts of the case and cover display enameled gold designs that are abstract versions of peapod ornament leaves. They are comparable in type to the abstraction found in a number of anonymous prints dated to the 1620s,[7] but a few of these motifs can still be found in prints from designs by the Parisian goldsmith Gédéon Légaré (1611–1676), especially some of those published by François Langlois, dit Ciartes (1588–1647), probably about 1635–40, but certainly before 1647.[8] The design of the Hubert watch dial was not, in fact, recognized as a variety of peapod design by some scholars, but considered instead to be the product of a nineteenth-century goldsmith.[9]

Further abstraction of the style appears on the enameled gold dial of a third watch with a rock crystal case in the Museum’s collection, this one signed only with the initials of the watchmaker, “M I,” on the back plate of the movement.[10] The movement is so small that the mainspring has been left open instead of being encased in a protective barrel, and a fusee has been omitted altogether. As might be expected, all of these watches are more clearly understood as jewelry that incidentally tells time rather than as serious timekeepers.

Rock crystal, a clear, transparent quartz that was in abundant supply in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe from deposits in the Alps, was an ideal medium for the display of increasingly decorative movements of watches. The embellishment of the movement’s pillars, set-up regulator, fusee stopwork, and balance cock made by skilled watchmakers; the moving wheels of the train, many with finely cut teeth; and above all the back-and-forth movement of the verge and balance could be observed through a transparent rock crystal case. The cutting, polishing, and engraving of rock crystal need both human skill and special equipment. Lapidary craftsmen concentrated in centers such as Paris, Venice, Milan, Florence, and Prague turned this craft into high art. But there were other, lesser-known centers; for example, lapidaries working in Freiberg im Breisgau, Germany, specialized in making necklaces and bracelets of rock crystal beads as well as other small objects for use by jewelers.[11] Very little is known, however, about the craftsmen who may have specialized in making rock crystal watchcases or about where they worked. Some were undoubtedly from Geneva, but surely they were not exclusively based there.

A few contemporary references found to either the watches with rock crystal cases or to other cases provide some evidence that these cases were used by watchmakers in widely divergent locations. For example, the will of the London clockmaker Bartholomew Newsam, dated in early 1585, states that he owned a “cristall Jewell with a watch in it,”[12] but we cannot be sure that the movement was made by Newsam or where he might have acquired it. In 1623 the Augsburg connoisseur and art agent Philipp Hainhofer (1578–1647) wrote to his German patron Prince August dem Junger of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1579–1664) about a crystal watch in the possession of the English ambassador to Venice,[13] adding in another letter[14] that a similar one could be made in the town of Kempten in Bavaria, presumably by the master clockmaker Georg Hipp.[15] By 1648, the estate of the Dutch goldsmith Minne Sikkes (active 1618, died 1648), who worked in the Friesian city of Leeuwarden, is known to have contained one large crystal watchcase and four smaller ones. We do not know where he obtained them.

Agen, a small city on the Garonne River about halfway between Bordeaux and Toulouse, would have been an unlikely place for fashioning rock crystal into watchcases. Further, the exquisite case of the Museum’s Vernède watch suggests that it must have been made in a center of skilled jewelers, which seventeenth-century Agen is not known to have possessed. The case consists of an elongated, octagonal band of rock crystal. The exterior surface of each of the eight sides is cut with a rectangle bordered by four trapezoids. A second border frames the first with rectangles alternating with trapezoids. On the interior surface of each facet of the cover is an engraved design of scroll embellishment, which is colored red and green and radiates from a central rosette. The crystal elements are all mounted in enamel and gold, each with a design drawn from the peapod vocabulary on a ground of black.

The dial expands on the peapod theme with symmetrical designs of leaves in opaque light blue, translucent green, opaque green, mustard, and white champlevé and painted enamels on a black ground. The chapter ring is created from a light-blue champlevé enamel that encompasses the numerals I–XII in gold for the hours and gold dots for the half hours. A single blued-steel hand completes the functional portion of the design. The enameled gold pendant at the top of the watchcase band continues the theme with three-dimensional peapods and peas covered with en ronde-bosse enamel and flanking a central floral bud that serves as the support for a loop for hanging the watch. A finial at the bottom of the band repeats the pea- and bud-shaped loop motifs. The plated movement fits snugly into the case held by four lugs and two spring catches that are manipulated by tiny knobs at the three and nine o’clock positions on the dial plate.

The movement, as exquisite as the case, consists of two elongated octagonal plates of gilded brass, which are held apart by four baluster-shaped pillars. The movement contains a train of three wheels with a verge escapement, a steel balance, and a tall, French-style fusee with fine grooves to accommodate a thin gut line. The back plate carries elaborately pierced and engraved ornament of gilded brass for the ratchet and click set-up regulator of the mainspring. A similarly elaborate ornamented cock for securing the top pivot of the verge staff is pinned to a post attached to the plate, and through a hole in the plate below the foot of the cock projects the winding square (the end of the steel shaft for winding the mainspring), its tiny tip embellished by shaped grooves in a Greek cross design. Below the cock the signature of the watchmaker is engraved, “P / Vernede / Agen.” Almost nothing is known of this maker except that he was apparently the first in a family of resident clockmakers in Agen who are recorded throughout the remainder of the seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century.[16]

The Noël Hubert watch in the Museum’s collection is encased in a single piece of hollowed-out rock crystal with a central trapezoid faceted on the exterior and surrounded by alternating triangles and trapezoids, including a second frame of trapezoids that forms the transition to the eight square and trapezoidal facets on the side of the case (fig. 24). A similar pattern of facets shapes the convex cover for the dial of the watch. Like the Vernède watch dial, the gold dial of this watch is embellished with champlevé and painted enamel on a black-enamel ground, but with a gold chapter of hours, the numerals (I–XII) in black enamel and the half hours marked by dots. A single, sculptural gold hand completes the face of the watch.

The movement, like the cover for the dial, is hinged to the mounting of the case and consists of two oval plates of gilded brass, which are held apart by four baluster-shaped pillars. It has three wheels and a verge escapement with a steel balance, a decorative set-up regulator for the mainspring, and a pinned on, openwork cock for securing the staff of the verge. The signature on the back plate now reads “Noel Huber (t) / A gros Hor / (lo)ge ARouen,” the partial effacement indicating that the arbors for the second and third wheels of the movement have been disturbed, either for repair or more likely replacement, and the back plate has been regilded. The Vernède watch movement is in good condition, but the finial at the bottom of the case is bent and most of its enamel lost. The pendant, too, has lost much of its enamel, and there are small losses to the enamel on both cases, especially in the areas around the catches for closing the covers and on the Vernède for securing the movement within the case.

It is not known where J. Pierpont Morgan acquired the Varnède watch, but the third one, signed with the initials “M I,” belonged to Carl H. Marfels of Frankfurt am Main and Berlin.[17]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] See, for example, Alcouffe 2001, pp. 379–98, including mounts by Pierre Delabarre and Jean Vangrol.

[2] For the trappings for the horse ridden by the Danish king Christian IV (1577–1648) at the wedding of his son in 1634, see Hein 2009, vol. 3, pp. 242–50, nos. 1010–18.

[3] Fuhring and Bimbenet-Privat 2002, pp. 5–7.

[4] For example, see the Carthusian Madonna with St. John the Baptist and St. Bruno spandrel decoration or the Conrad Celtes Presenting the Quattuor Libri Amorum to Maximilian I, Nurnberg, Apr. 13, 1502; Knappe 1965, figs. 324 and 210,

respectively.

[5] Fuhring and Bimbenet-Privat 2002, pp. 9–10.

[6] Acc. no. 17.190.1594.

[7] Fuhring and Bimbenet-Privat 2002, pp. 51–63.

[8] Ibid., pp. 112–14.

[9] Recent analyses by Mark T. Wypyski, Research Scientist in the Metropolitan Museum’s Department of Scientific Research, have confirmed the composition of the enamel to be compatible with that of seventeenth-century enamel, rather than that in use during the second half of the nineteenth century.

[10] Acc. no. 17.190.1551. The watchmaker M. I. has not been identified, but he was probably German. He was not Matthew Ive, as proposed in Williamson 1912, pp. 128–29.

[11] Irmscher 1997, p. 34.

[12] The will of Bartholomew Newsam, Clock Maker of Saint Mary in the Strand, Middlesex, probated on Dec. 18, 1593, Neville Quire Numbers 48–96, Public Record Office, National Archives. See also entry 5 in this volume for more about Newsam.

[13] Gobiet 1984, p. 374.

[14] Ibid., p. 378.

[15] See Maurice 1976, vol. 1, p. 175. Hipp was listed among notable citizens of Kempten in Zorn 1820, p. 67.

[16 Tardy 1971–72, vol. 2, p. 639. See also Hayard 2004, p. 135. Williamson 1912, pp. 1 and 2, confused Jean Vernede, one of the eighteenth-century Vernedes, with Pierre Vernede.

[17] Williamson 1912, pp. 128–29, no. 130.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.