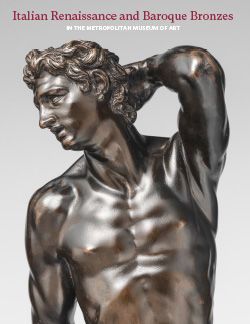

David with the head of Goliath

Not on view

The present writer unmasked this and an identically solid-cast and unchased statuette,[1] formerly in the Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, as brazen, inept imitations of the excellent David in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which is usually called Bellano but here given to Severo Calzetta da Ravenna in his formative years (see cat. 2). And this despite the claimed descent of our bronze from Sienese collections of some repute and its frequent endorsement as a work of Luca della Robbia, whose oeuvre contains nothing resembling it and little in the way of bronze, for that matter. Nevertheless, for John Pope-Hennessy, “the possibility cannot be ruled out that it was modelled by Luca della Robbia and cast in the shop of Maso or Giovanni di Bartolomeo.” It is pointless to consider these or other Renaissance names. Some traits absolutely rule out the quattrocento: a bleary expression, shapeless pageboy haircut, lifeless tunic (beneath which there are neither genitals nor breeches), and a sword handle the same width as the weapon. The smallness of Goliath’s head, hardly bigger than David’s, is another blunder. Alarmingly, the right wrists of both statuettes are broken in precisely the same place.

In view of the late facture, the provenance demands reexamination. Ostensibly, the first mention of our bronze occurred in 1810, when Galgano Saracini recorded the “bronze David sold me by Bastiano,” who has not been identified.[2] The situation around 1810, when early Renaissance bronzes were not yet avidly sought, probably rules out its being made near or before that time. Yet another bronze remains in the collection of Palazzo Chigi-Saracini, Siena, now belonging to the Monte dei Paschi di Siena.[3] Although well published, those holdings do not contain noteworthy pre-seventeenth-century sculptures, and the earlier works among them generally bear frightfully ambitious attributions. It must be asked whether some member of the Chigi-Saracini-Piccolomini della Triana tribe did not have an interest in inventing and promoting three poor, virtually identical bronze Davids as authentic relics of the quattrocento.

-JDD

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Sotheby’s, New York, May 21, 1985, lot 97 (as after a Renaissance model).

2. Gentilini and Sisi 1989, p. xxiv.

3. Ibid. Thanks to Barbara Valdambrini of the Fondazione Accademia Musicale Chigiana, Siena, for confirming the existence of this bronze (6417), now catalogued as nineteenth century.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.