Longcase clock with calendar

Clockmaker: Daniel Delander British

Not on view

Improvements to the technology of seconds-beating pendulum clocks by the English continued throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The anchor escapement, probably the invention of Joseph Knibb about 1668–69,[1] was followed in 1676 by the rack-and-snail mechanism by Edward Barlow (1638–1719), whereby the striking of a clock was directly tied to the position of the hour hand that could be manipulated directly. Although the new mechanism no longer needed the more laborious adjustments to the striking required by a count wheel, several problems remained to be solved, including the effect of temperature changes on the pendulum. A few years before 1726 George Graham (1673–1751), Thomas Tompion’s (1639–1713) former partner and successor to the firm, began experimenting with a pendulum ending in a cylinder of mercury that replaced the familiar brass-covered bob. Graham’s publication of the invention appeared in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (1726–27).[2] A few years later John Harrison (1693–1776), better known for his invention of the marine chronometer, introduced his bimetallic gridiron pendulum. Although he probably devised it as early as 1732, John Ellicott (1706–1792) did not publish his compensation pendulum until 1753.[3] Ellicott’s pendulum, however, was never as widely adopted by clockmakers as the first two.

Another problem in making the English longcase clock the remarkably accurate timekeeper it became was caused by the slight recoil of the early anchors of the escapement as they rocked back and forth, alternately giving impulse to and locking the escape wheel. Graham is usually credited with the invention of about 1730 of the recoilless, or dead-beat, escapement. There is evidence, however, that there had been attempts to overcome the problem as far back as Tompion’s escapements of 1675 for the year-going clocks he made for the Royal Observatory in Greenwich (see entry 28 in this volume). Tompion’s original escapements were apparently not successful, and they were soon replaced by Richard Towneley’s, but these were subsequently modified by Tompion.[4] Nevertheless, the improved escapement for long pendulum clocks was not settled until Graham’s time.

There is some evidence that other forms of recoilless escapements were being made.[5] One of them was the duplex, a device using two escape wheels that cut the amount of recoil in half. Escapements using the duplex principle, but in different configurations, were still being published as late as 1741, notably by Antoine Thiout l’aîné (1694–1767), whose technical treatise on horology (fig. 9) included, along with an example of the Graham dead-beat, a duplex escapement invented by the French clockmaker Jean-Baptiste Dutertre (1684–1734).[6] The duplex in the Metropolitan Museum’s clock is usually called the Delander duplex after its probable inventor, Daniel Delander (1678–1733).[7] Delander, the son of Nathaniel Delander, the maker of some of Tompion’s most beautiful watchcases, was baptized at Saint Sepulchre, Holborn, in 1678.[8] His apprenticeship to the clockmaker Charles Halstead is recorded in April 1692 in the Clockmakers’ Company Court Minute Books.[9] His admission to the company as a Freeman in July 1679 described him as still an apprentice of Halstead’s,[10] but by July 1695, he had been turned over from Halstead to Tompion, for whom he apparently continued to work until setting up his own shop at The Dial in Deveraux Court about 1706.[11]

The Metropolitan Museum’s longcase clock, numbered 13, belongs to a small group of clocks with numbers on their dials that apparently fall outside of Delander’s regular production. Not all of the group can now be found, but number 18 is the highest numbered example recorded. The group is difficult to date. Delander apparently remained in close touch with Tompion’s successor, Graham, however, and it seems likely that Delander’s duplex predated Graham’s deadbeat, which was capable of greater accuracy but required more precision in its construction. If Delander’s escapement is earlier than Graham’s, it is probably not by very much.

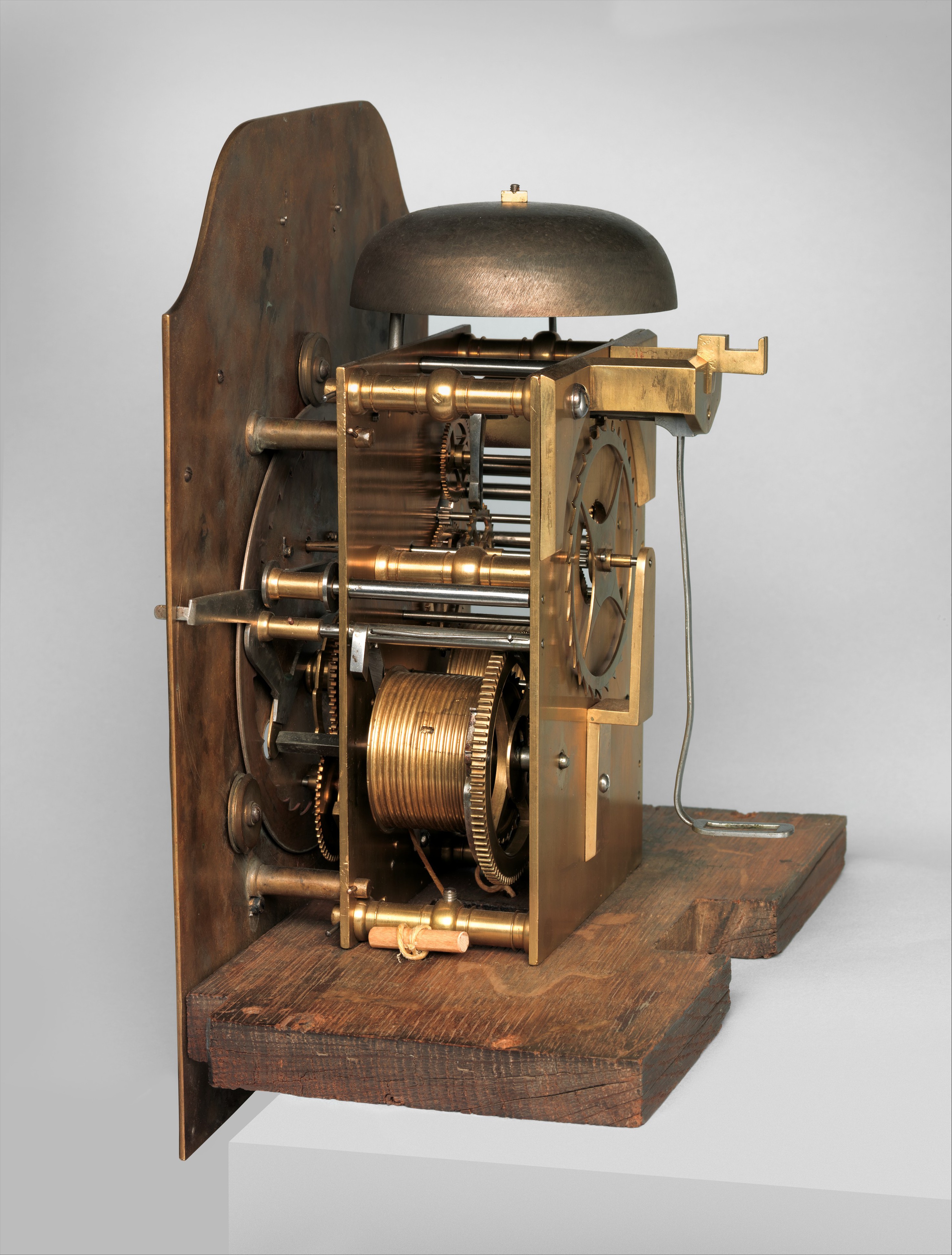

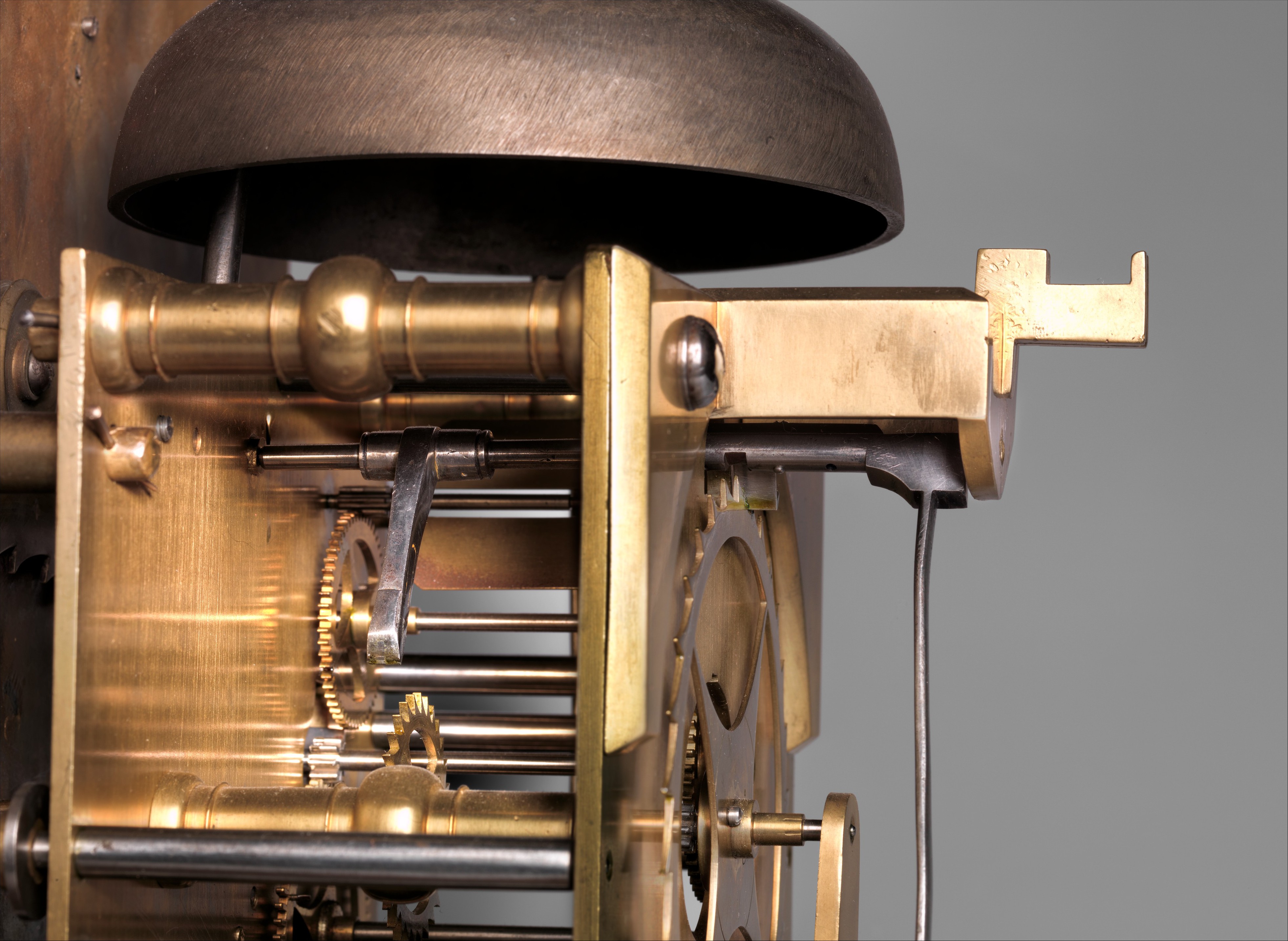

The eight-day, weight-driven movement of the Museum’s clock consists of two rectangular plates, which are made of unusually thick brass and held apart by five turned pillars. A going train of three wheels and two separate escape wheels (a small wheel inside the movement for transmitting the impulse and a large one outside the back plate for locking) are mounted on a single arbor. The escape wheels are controlled by two pallets that are separately attached to the arbor of the pendulum crutch. Thus, the impulse is provided by only one pallet per excursion of the pendulum instead of two, which cuts the number of periods of recoil in half.

The striking train consists of four wheels and a fly. It is controlled by a rack-and-snail device with the rack mounted inside the front plate and the snail on the exterior of the plate. It strikes the hours on a bell that is mounted on the front plate.

The flat arched dial is of gilded brass. It has a wide, silvered-brass chapter ring for the hours (I–XII); for the minutes (5–60, by fives); and for the half hours, marked by diamonds. At the twelve o’clock position there is a silvered-brass chapter ring for seconds that reflects the period of the pendulum’s excursion (6–60, by sixes) and at the six o’clock position an aperture for display of the day of the month. The center of the dial has a matte finish, and the spandrels are filled with human masks sporting bibs and surrounded by foliate ornament. The sculptured hour and minute hands are made of blued steel, and on the right side of the dial, located between the two and three o’clock positions, is a slot to accommodate the lever for connecting the clock’s maintaining power.

The case is made of burl walnut veneered on oak. Applied wooden moldings outline the skirt, the hexagon on the plinth, and the door of the trunk. The inlays of herringbone- patterned walnut repeat the pattern on the plinth and trunk. The plinth, trunk, and hood have chamfered corners, and the flat arched motif of the dial is repeated on the door to the trunk, the door to the dial, and the molding above the dial. This design is extremely rare in English clockcases of the first quarter of the eighteenth century.

The forward-sliding hood has a hinged, glazed door with a lock. Applied gilded-brass ornaments of flowers and fruit are suspended from ribbon bows that adorn the chamfered surfaces and flank the door to the dial. Pierced and gilded-brass ornaments fill the openings in the sides of the hood. These ornaments consist of central term figures, which are flanked by seated infants and foliate ornaments punctuated by vases and masks, and backed by fabric, permitting the sound of the bell to escape the hood. The crest has three tiers at present: a platform supporting two pedestals with gilded metal finials, an inverted bell top, and a pedestal and gilded-metal finial atop a domelike element.

The maker of the case is unknown, and its date is as uncertain as it is for the movement. Delander clock number 11 in the series with duplex escapements is housed in a case that is close in style to clocks with conventional escapements usually dated to the early eighteenth century.[12] Number 13 and number 17, as historian Percy Dawson has pointed out, have the distinct features found on the case of a clock by John Ellicott (1706– 1792) probably not made before 1730.[13] Ellicott continued to use this design for clockcases that incorporated his compensated pendulums. But Dawson’s conclusion that the Delander cases should be dated about 1730 seems too late if the correlation of Delander’s experimental escapement with Graham’s more successful dead-beat escapement of about 1720 is correct.

Inscriptions inside the movement of the Museum’s clock indicate that it was repaired in 1840 and 1885. At some point, the functioning of the escapement was misunderstood, and the pallets were positioned in such a way that the arc of the swinging pendulum was wider than the trunk of the case. Openings were made in the sides of the trunk to accommodate the arc, and these were fitted with earlike wooden attachments. These additions are visible in an illustration of the clock published in 1937, when it was on loan to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.[14] They were still evident in the 1948 sale catalogue for the collection of the clock’s owner.[15] At some point, the two additions were removed by someone who apparently did not understand why they had been added. It remained for the Museum’s conservator of clocks in the early 1970s to reposition the pallets of the escapement so that the pendulum could swing without hitting the trunk and stopping the clock.

The three finials and the extra dome atop the hood were in place in 1937, as the Virginia catalogue documents. It is not certain when they were added to the hood and not entirely certain what they replaced. Small losses to the wooden moldings and a missing gilded-metal ornament have been replaced by the Museum’s conservators.

Henry P. Strause of Washington, D.C., placed his collection of clocks on loan to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 1936.[16] The collection remained on view there until it was sold in 1948.[17] The clock was bought at the 1948 sale by Irwin Untermyer,[18] the donor to the Metropolitan Museum.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] See 1974.28.92 in this volume.

[2] Graham 1726–27, p. 40.

[3] Ellicott 1751–52. Like Graham, Ellicott was one of the very few clockmakers who were members of the Royal Society. For a summary of Ellicott’s paper, with commentary on the Graham and Harrison inventions, see Baillie 1978, pp. 233–35. See also Foulkes 1960; Robinson 1981, pp. 387–89.

[4] Howse 1970–71, pp. 22–24. See also J. L. Evans 2006, pp. 22–23.

[5] Robinson 1981, pp. 45–46.

[6] Thiout 1741, vol. 1, pp. 101–2, and pl. 41, figs. 15, 16.

[7] See, for example, Robinson 1981, pp. 161–62.

[8] The authors are indebted to Jeremy L. Evans, formerly of the British Museum, London, for the date and place of Delander’s baptism as well as evidence of his relationship to Nathaniel Delander.

[9] Clockmakers’ Company, London, Court Minute Books, Ms. 2710/2, 1680–99, p. 126v, Guildhall Library, London.

[10] Ibid., p. 230r.

[11] The authors are indebted to Jeremy L. Evans for sharing evidence of the change of apprenticeship.

[12] Phillips 1998, p. 64, no. 333, ill.

[13] Dawson 1987.

[14] Virginia Museum of Fine Arts 1937, p. 35, no. c-33, and pl. vii.

[15] Parke-Bernet Galleries 1948, p. 62, no. 241, ill. p. 63.

[16] Virginia Museum of Fine Arts 1937.

[17] Parke-Bernet Galleries 1948.

[18] Hackenbroch 1958, p. 7, and pl. 6, fig. 9.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.