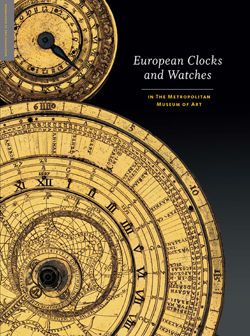

Astronomical table clock

Movement probably by Jeremias Metzger German

Signed by Caspar Behaim (Chasparus Bohemus) Austrian

To a large extent, collections in sixteenth-century Europe reflected the interests of those who were powerful or wealthy enough to form them. In German-speaking areas, in particular, many collectors were greatly influenced by the theoretical concept of the Kunstkammer as an assemblage of objects organized to display the owner’s cognizance of both the natural world and the products of human artifice. Many Kunstkammern, but by no means all, contained at least a few mathematical instruments, globes, and clocks. The clocks prized for inclusion in a Kunstkammer customarily displayed not only the time in several different systems for counting the hours, but also as much calendrical and astronomical information as the clockmaker could devise.[1]

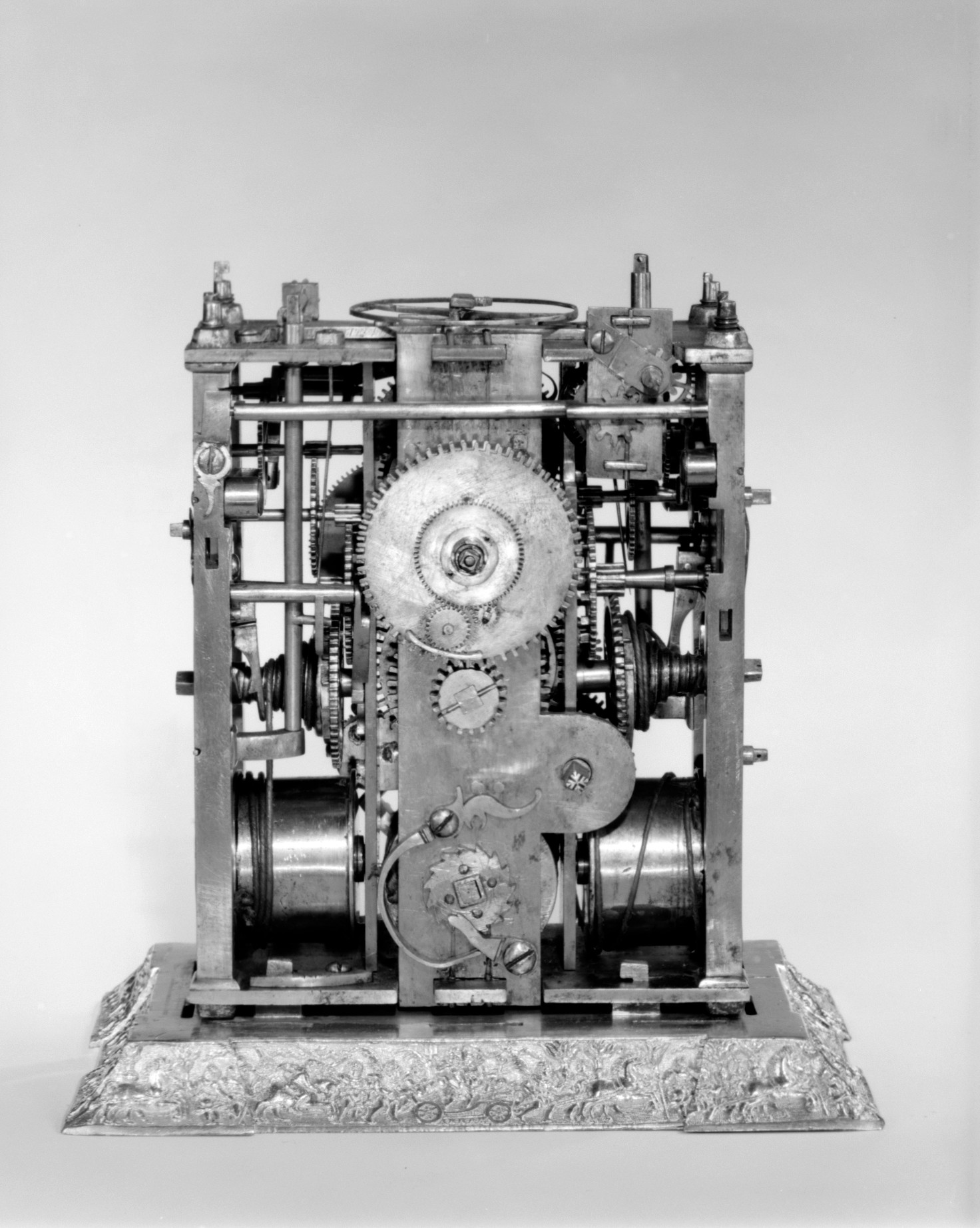

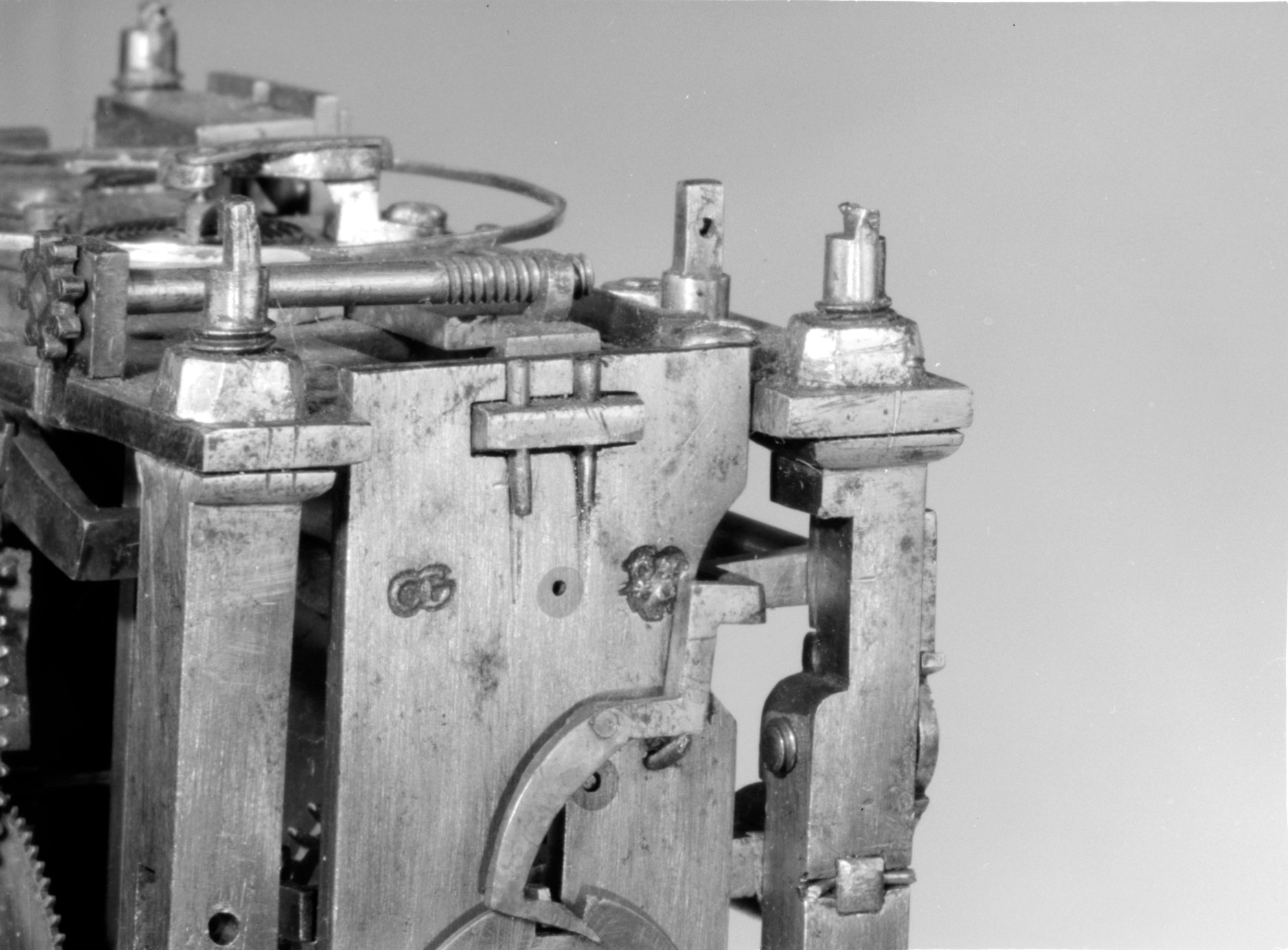

The Behaim clock, because of its astronomical and calendrical dials, would have been an ideal addition to any Kunstkammer. It belongs to a series of clocks made from a comparable construction known as Metzger-type clocks, because some of them are signed by the clockmaker Jeremias Metzger, or Metzker (ca. 1525–ca. 1597). Like other clocks in this series, the clock has a spring-driven movement, consisting of two rectangular plates that are held in place at the four corners by iron pillars, a structure that supports three trains of wheels. The train in the center drives the dial for time telling, or length of day, on one long side of the clock, as well as an astrolabe dial on the other long side. The principle arbor of this train is perpendicular to the dials on the exterior of the long sides of the clock and projects through the dials to carry the hands (now missing). The central train is flanked by two trains set at right angles. These trains primarily operate the hammers that strike two bells on stands that are attached to a plate at the top of the clock, one for hours and one for quarters. With a few exceptions, this construction is the essence of a Metzger-type clock. Although the product of more than one clockmaker, this group of clocks was first identified by historian Erwin Neumann, who chose as his prototype a clock in the collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, signed: “Jeremias 1564 Metzker Vrmacher, Vrmacher in Augspur.” The movement also bears his punchmark, consisting of his monogram, “I M,” within a shield, as well as the pinecone, or pyr, the town mark of Augsburg, Germany.[2]

Like the case of the clock in Vienna, the case of the Museum’s clock is rectangular, with applied colonettes at the corners, which are set upon a base ornamented with cast reliefs depicting triumphal processions and supporting an openwork dome with interlaced foliage inhabited by figures variously engaged in hunting bear and ducks. Partial figures of winged horses spring from the four corners where the dome joins the main body of the clock. The astrolabe dial was probably intended as the front of the clock, because the winding square for the mainspring of the time train projects through a hole in the case just below the astrolabe, therefore facilitating the insertion of the key. The revolving rete of the astrolabe on this clock shows the positions of fourteen stars, and it has two reversible tympans (or plates) for use in latitudes of 45, 48, 51, and 54 degrees. A subsidiary dial, which is driven by the astrolabe, revolves to show the days of the week with their planetary rulers. This dial is flanked by two female figures cast in relief: one figure is accompanied by a monkey that wields a pointer to mark the days, and the other figure is holding a nautilus shell. At the top of the same side are personifications of two of the Four Winds.

The other long side has two large circular dials, including a chapter ring that shows the time (I–XII, twice), an inner ring that now shows the time in Arabic numerals (1–12, twice), and an outer ring that shows the quarter hours (I–IIII) and is also marked for minutes (the latter markings probably not original to the clock). In the center, there is a disk for setting the clock’s alarm, and between this disk and the three chapter rings is a large open space that once contained movable shutters, one for the number of daylight hours and one for the night hours (Nürnberg hours). At the lower right is a subsidiary dial (hand now missing) showing the months with their associated zodiacal signs that functioned as an adjustment for the shutters according to the time of the year. The other large dial (lower left) is equipped with three revolving circular plates, which are engraved with the days of the year and indicate holidays and Saints’ Days. A draped female figure holds a staff that points to the day. Beside her is an eagle and above her a subsidiary dial with the Dominical Letters (hand manipulated). A somewhat larger subsidiary dial (a later addition), at the top right, regulates the spring balance. Two other female figures in relief complete the side, one seated with a dog, and the other playing a viol.

The short side to the left of the astrolabe registers the quarter-hour striking, and the short side to the right registers the hour striking. The dial below the latter allows for adjusting the mechanism to strike twelve or twenty-four times as desired. The twenty-four-hour striking (now inoperative) has a subsidiary count wheel (sometimes erroneously called Canonical striking), in addition to the usual count wheel that serves to make the twenty-four-hour striking more reliable.[3]

Close comparison of the Museum’s clock with the clock in Vienna makes it evident, as clock historian Klaus Maurice has proposed, that in spite of the inscription on the case and the punchmarks on the movement, the Museum’s clock must have been made by the same clockmaker and probably the same casemaker as the Vienna clock.[4] Other clocks belonging to this group and signed by Metzger are now known to be in the collection of the Nicolae Simache Clock Museum, Ploiesti, Romania (dated 1562), [5] and the James A. de Rothschild Collection at Waddesdon Manor near Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, England (dated 1563).[6] Still, other clocks with similarly constructed movements also exist. While there is no documentary evidence that the Museum’s clock was actually made by Jeremias Metzger, or in his workshop, the supposition can be supported by some of what is known about Metzger and about Behaim. Metzger, born in Augsburg about 1525, was a highly successful maker of small clocks and seemingly an influential member of the newly created Augsburg guild of clockmakers owing to the fact that he is recorded as an inspection master for the guild (Geschaumeister) in 1564. Nevertheless, he apparently ran afoul of the rules that governed the activities of journeymen in Augsburg, probably because the demand for his clocks outstripped the traditional supply of skilled labor.[7] Caspar Behaim (or Behaimb, or Beham, or Chasparus Bohemus; active 1568–84), whose latinized name appears conspicuously on the case of the Museum’s clock, is recorded as a clockmaker working in Vienna between 1573 and 1584 and paid for work on the Viennese city hall (Rathaus) clock in 1578.[8] The city hall clock would undoubtedly have been a large, wrought-iron framed turret clock requiring very different skills than those of a maker of small clocks who would have used different tools. It seems reasonable, therefore, to suppose that Behaim must have had an Austrian patron for whom he obtained the clock from a well-established maker of small clocks in Augsburg, the most important center of German clockmaking. The connection between the two clockmakers remains unknown.

Clockmakers in Nürnberg, Augsburg’s chief competitor in the second half of the sixteenth century, seem to have owned some of the models for the cases of their clocks.[9] Ownership of models is less certain in Augsburg, but at least some clockmakers are known to have produced their own cases. Historian Eva Groiss cites records in the Stadtarchiv Augsburg that show five goldsmiths were permitted to specialize in making clock cases by 1567. Metzger was, in fact, one of the clockmakers for whom the goldsmith and embosser Hans Helmbrecht (active 16th century) is known to have worked.[10] But the Metropolitan Museum’s clock case is made of brass, in large part cast brass, and thus fell at least partly under the jurisdiction of the brass founders, who were even more restricted than the goldsmiths of Augsburg. Surviving evidence, nevertheless, indicates that these shops were capable of serial production of the cast-brass components of clockcases. [11] For that reason, the case of the Museum’s clock was probably the work of several skilled craftsmen, one of whom may, indeed, have been Metzger.

The applied figures on the cases of the Metzger clocks in the Kunsthistorisches Museum and Waddesdon Manor, as well as the Behaim clock, are prime examples of serial casting from the same models. It has been suggested that the figures represent personifications of the Five Senses.[12] The source of the processions on the front and back of the base of the clock has long been known as a print by Hans Sebald Beham (1500–1550), dated 1549, which has had various titles but appears in a publication by a recognized authority on German prints and is titled The Triumphal Procession of the Noble Glorious Women.[13] Noted historian of decorative arts Geoffrey de Bellaigue identified the figures in the dome in three engravings by Virgil Solis (1514–1562) of Nürnberg,[14] the long sides from the right side of a bear hunt (Barenjagd)[15] and the short sides from the centers of two engraved duck hunts (Entenjagd).[16]

The plates that form the sides of the case are particularly felicitous examples of a variety of ornament usually identified as moresque, which Italian artists adapted from Islamic sources and spread throughout Europe through the medium of prints. No exact model for the ornament of the plates of the Behaim and Metzger clocks has been found, but somewhat comparable designs appear in prints signed with the initial “f,” an anonymous Italian who probably worked in Venice, and whose ornament was republished about 1550 by the printmaker Hieronymus Cock (1518–1570) in Antwerp.[17] This variety of ornament found its way into the prints of the Dutch-born Balthazar Sylvius (Balthasar van den Bos/Bosch, 1518–1580), also working in Antwerp, whose designs of the 1550s and 1560s combined pure moresques with patterns of interlaced strapwork [18] in a style that is beautifully employed on the sides of the case of the Behaim clock.

Unlike many late-Renaissance clocks, this one was not converted to a pendulum. Instead, the original circular balance was fitted with a balance spring, probably not long after the invention by the Dutch mathematician Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) was published in 1675. At the same time the chapter ring for Italian hours (1–24, starting at sundown) of the time-telling dial was replaced by a chapter ring (reading 1–12, twice), and the outermost ring was marked for minutes, now practical given the greater accuracy of the newly invented spring balance. Two new plates for the calendar were added, one given the names of saints favored by the Dutch, and the other now displaying the Dutch word for Christmas (Kerstmis), suggesting that the conversion was made in the Netherlands.

The clock is now missing most of its hands and the movable shutters adjusting the length of the days and nights. A new finial for the dome was supplied in Paris by Alfred André (1839–1919) at some time between 1886 and 1893.[19] In addition, an ebony base of uncertain age was supplied for the clock before it entered the collection of the Museum’s donor J. Pierpont Morgan. The clock had earlier belonged to Frédéric Spitzer in Paris (1893),[20] who may have added the André finial. Before Spitzer the clock belonged to Charles Stein, who sold it in Paris in 1886.[21]

At some point in the nineteenth century at least one copy of the case of the Museum’s clock was made probably as an electrotype.[22] The copy is not to be confused with the much larger edition of electrotype made by the Viennese firm of C. Haas and Company in 1864 or 1865 from the Metzger clockcase in the Kunsthistorisches Museum,[23] examples of which can still be found throughout the world.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] Leopold 1995. See also Daston and Park 1998.

[2] Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (inv. no. 852). See Neumann 1961, pp. 91–101, 110–11.

[3] See Leopold 1971, pp. 52–53, for an explanation of this mechanism.

[4] Maurice 1976, vol. 1, p. 105, and vol. 2, pp. 29–30, nos. 158, 159, and figs. 158a–d, 159a–e.

[5] The authors are grateful to Paulus Rainer of the Kunsthistorisches Museum and to the staff of the Nicolae Simache Clock Museum for this information.

[6] See de Bellaigue 1974, vol. 1, pp. 146–53, no. 29.

[7] See Clockwork Universe 1980, p. 189, no. 26.

[8] Uhlirz 1897, p. xcvii, no. 15809, fol. 110 (1573), and p. cxi, no. 15833, fol. 68 (1584).

[9] Leopold 2002, pp. 522, 524–25.

[10] Groiss 1980, pp. 70–71 and n. 82.

[11] Maurice 1976, vol. 1, pp. 99–107; Groiss 1980, pp. 70–71 and n. 82.

[12] De Bellaigue 1974, vol. 1, p. 152.

[13] Hollstein, German, 1954–2014, vol. 3 (1954), p. 145.

[14] De Bellaigue 1974, vol. 1, pp. 151–52.

[15] O’Dell-Franke 1977, p. 134, no. g 1, and pl. 71.

[16] Ibid., p. 139, nos. g 39 and g 40, and pl. 77.

[17] Byrne 1981, pp. 32–33, nos. 13, 14.

[18] Ibid., p. 36, no. 20.

[19] The authors are indebted to the late Rudolf Distelberger, formerly of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, for the evidence of the origin of the finial figure.

[20] Collection Spitzer 1891–93, vol. 5 (1892; plate vol.), “Horloges,” pl. iv; Palustre 1892, p. 37, no. 7.

[21] Galerie Georges Petit 1886, p. 56, no. 215.

[22] Hotel Drouot 1981, no. 47. 23 Neumann 1961, p. 121.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.