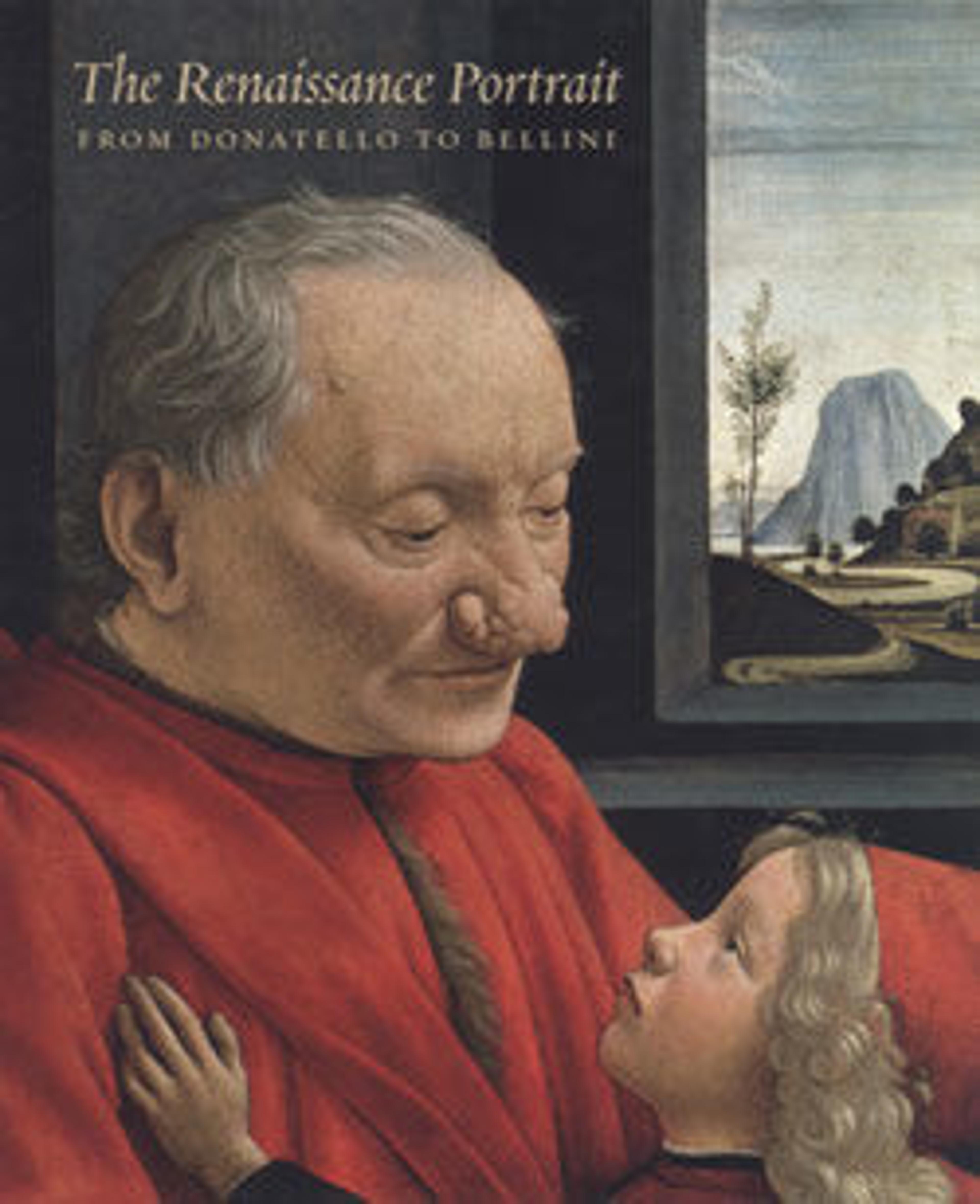

Portrait of a Man

While Rosselli made a habit of inserting the likenesses of his contemporaries into his religious paintings, this is a rare example of an independent portrait. The sitter’s clothing suggests he was a member of the Florentine nobility, possibly even one of the priori, members of government whose uniform was a crimson coat lined with ermine fur. The sitter places his hand on the edge of the frame; Rosselli likely adapted this motif from the Netherlandish portraits of Hans Memling, whose works were commissioned by Italian patrons and exported from Bruges thanks to a well-developed international art market.

Artwork Details

- Title: Portrait of a Man

- Artist: Cosimo Rosselli (Italian, Florence 1440–1507 Florence)

- Date: ca. 1481–82

- Medium: Tempera on wood

- Dimensions: 20 3/8 x 13 in. (51.8 x 33 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Bequest of Edward S. Harkness, 1940

- Object Number: 50.135.1

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please complete and submit this form. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.