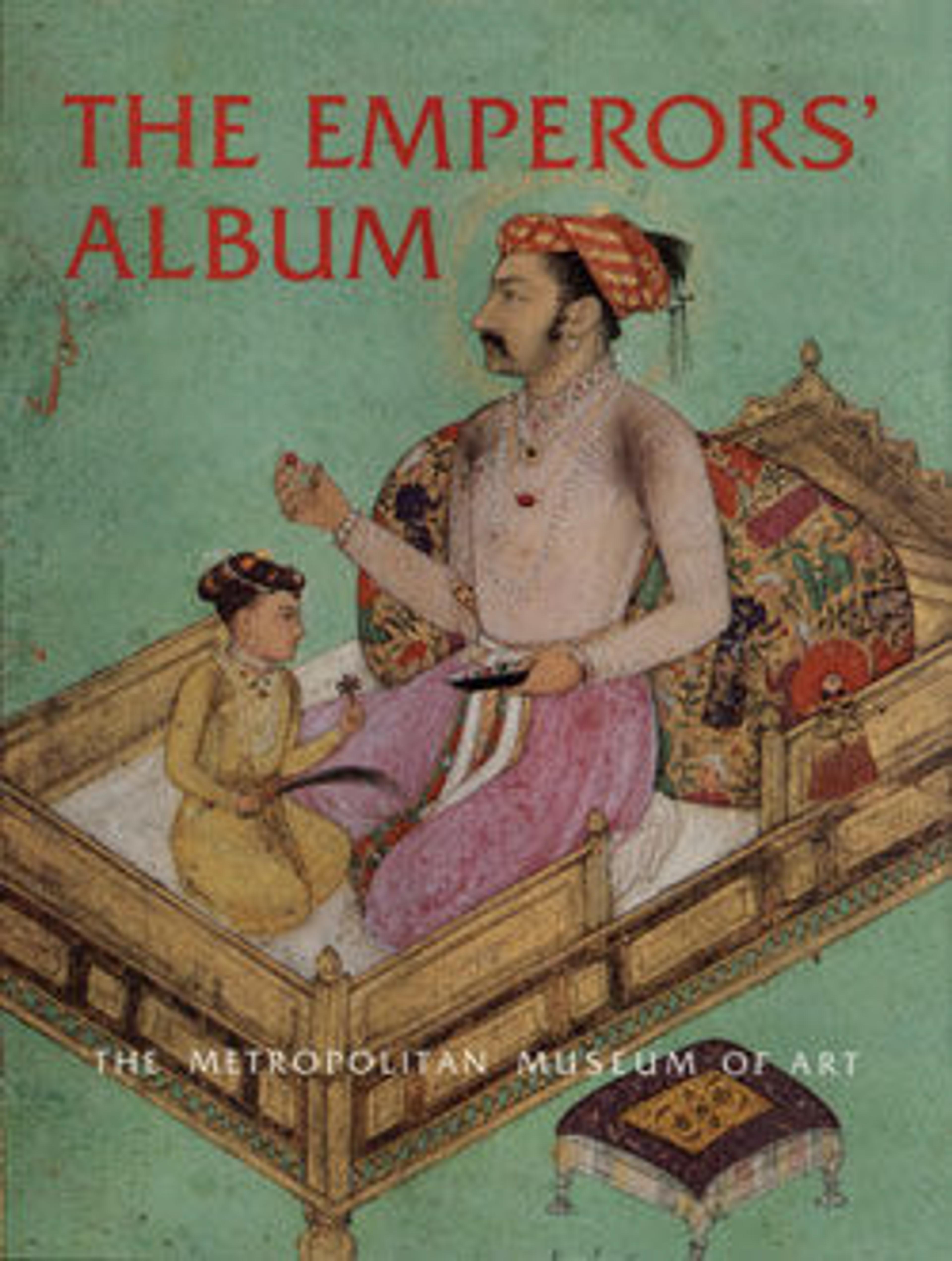

"Portrait of Zamana Beg, Mahabat Khan", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

This page comes from an album that combined Mughal paintings executed during the reigns of Shah Jahan and of his father and predecessor, Jahangir; classic examples of sixteenth century Persian calligraphy, highly prized by India's Muslim rulers; and nineteenth-century copies of seventeenth-century Indian paintings. Like many other seventeenth-century illuminated margins in the album, this one reveals a new Mughal taste for highly naturalistic flowering plants shown in profile. This flower style had its origins in flower paintings commissioned by Jahangir on a trip to Kashmir in the spring of 1620. Within ten years the style was adapted to architectural decoration and thereafter became popular in the decoration of all media.

Artwork Details

- Title: "Portrait of Zamana Beg, Mahabat Khan", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album

- Artist: Painting by Manohar (active ca. 1582–1624)

- Calligrapher: Mir 'Ali Haravi (died ca. 1550)

- Date: recto: ca. 1610; verso: ca. 1530–40

- Geography: Attributed to India

- Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

- Dimensions: H. 15 1/4 in. (38.7 cm)

W. 10 5/16 in. (26.2 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift, 1955

- Object Number: 55.121.10.3

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please complete and submit this form. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.