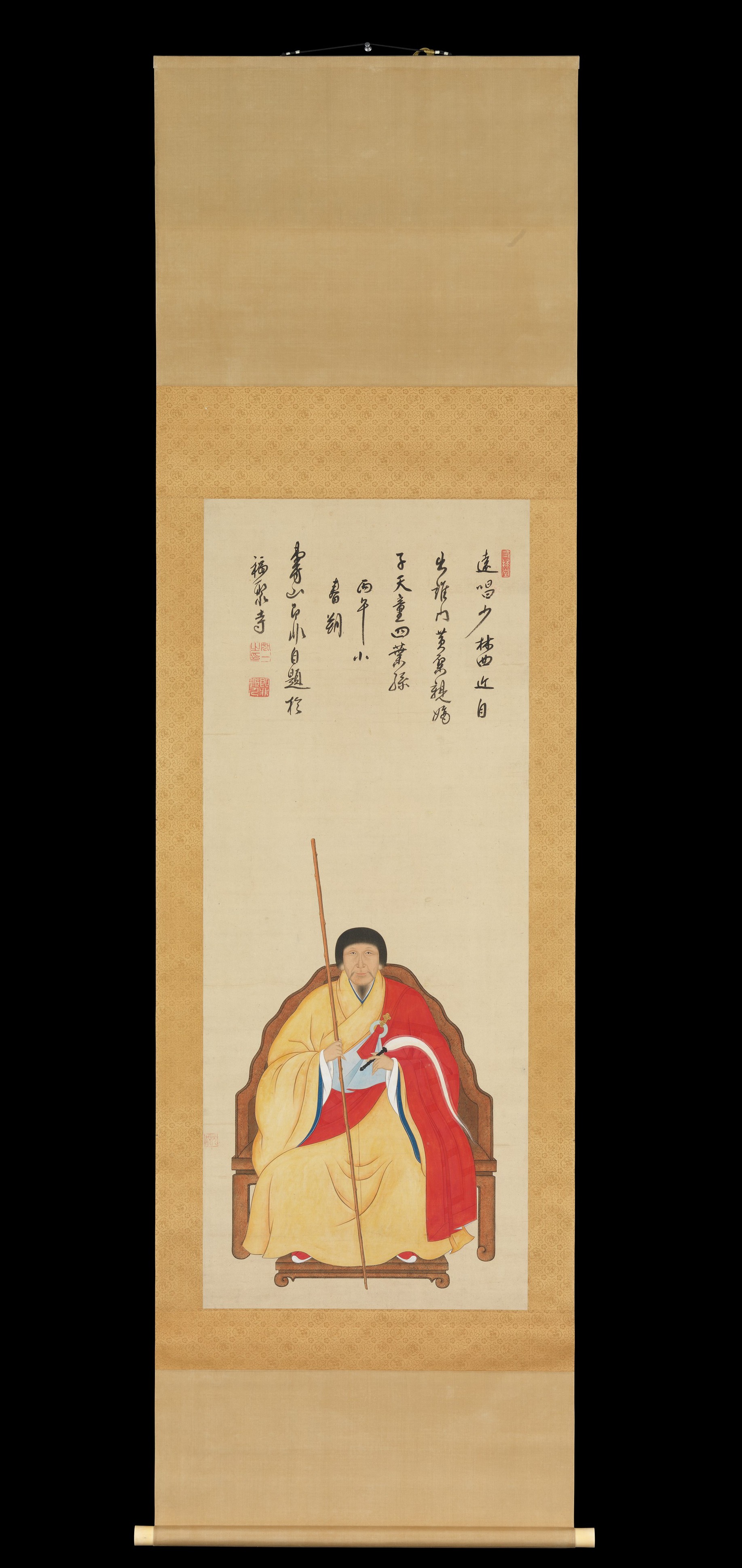

Portrait of the Ōbaku Zen Monk Jifei Ruyi (Sokuhi Nyoitsu)

Painting by Kita Genki Japanese

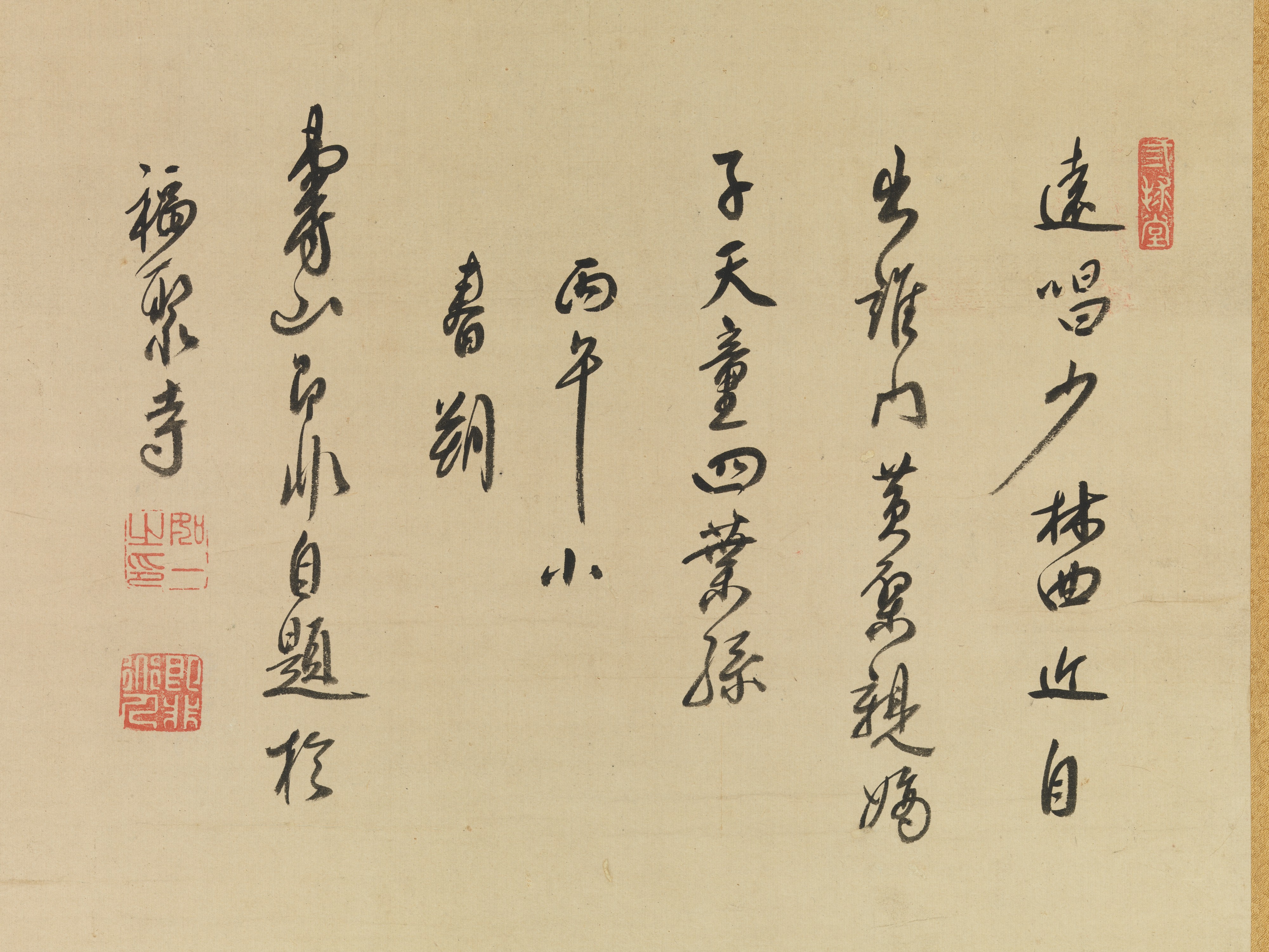

Inscription by Jifei Ruyi (Sokuhi Nyoitsu) Chinese

Not on view

Genki, a Nagasaki artist, painted this portrait of the Ōbaku master Jifei Ruyi (Japanese Sokuhi Nyoitsu), which was inscribed in Chinese by the subject himself while he was resident at Fukujuji, a temple patronized by the daimyo of Kokura (present-day Kita Kyushu Kitakyūshū). The port of Nagasaki was one of the few places under the tightly regulated Tokugawa government where contemporary Chinese culture and learning could be openly discussed and studied. In the mid-seventeenth century, new ideas on Confucianism and Zen (Chinese: Chan) Buddhism were brought to Japan by Chinese monks travelling through Nagasaki (including Jifei Ruyi) and by envoys from Korea. These monks formed what was known in Japan as the Ōbaku school, after the Japanese rendering of the name of the Tang dynasty monk Huangbo Xiyun (d. 850).

There are several versions of this portrait, each with a different inscription. In Zen, the teachings of the Buddha Shakyamuni are transmitted directly from teacher to pupil; in seventeenth-century practice, as in earlier ages, the Buddha's word lived in receiving instruction rather than in reading texts. A portrait of one's teacher, suitably inscribed, was a venerated symbol of accomplishment and a tangible reminder of the special relationship around which knowledge was structured. Since the Kamakura period (1185–1333), portraiture and inscriptions have merged religion, autobiography, and biography in images of great power, as in this hanging scroll.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.