The Female Pharaoh Hatshepsut

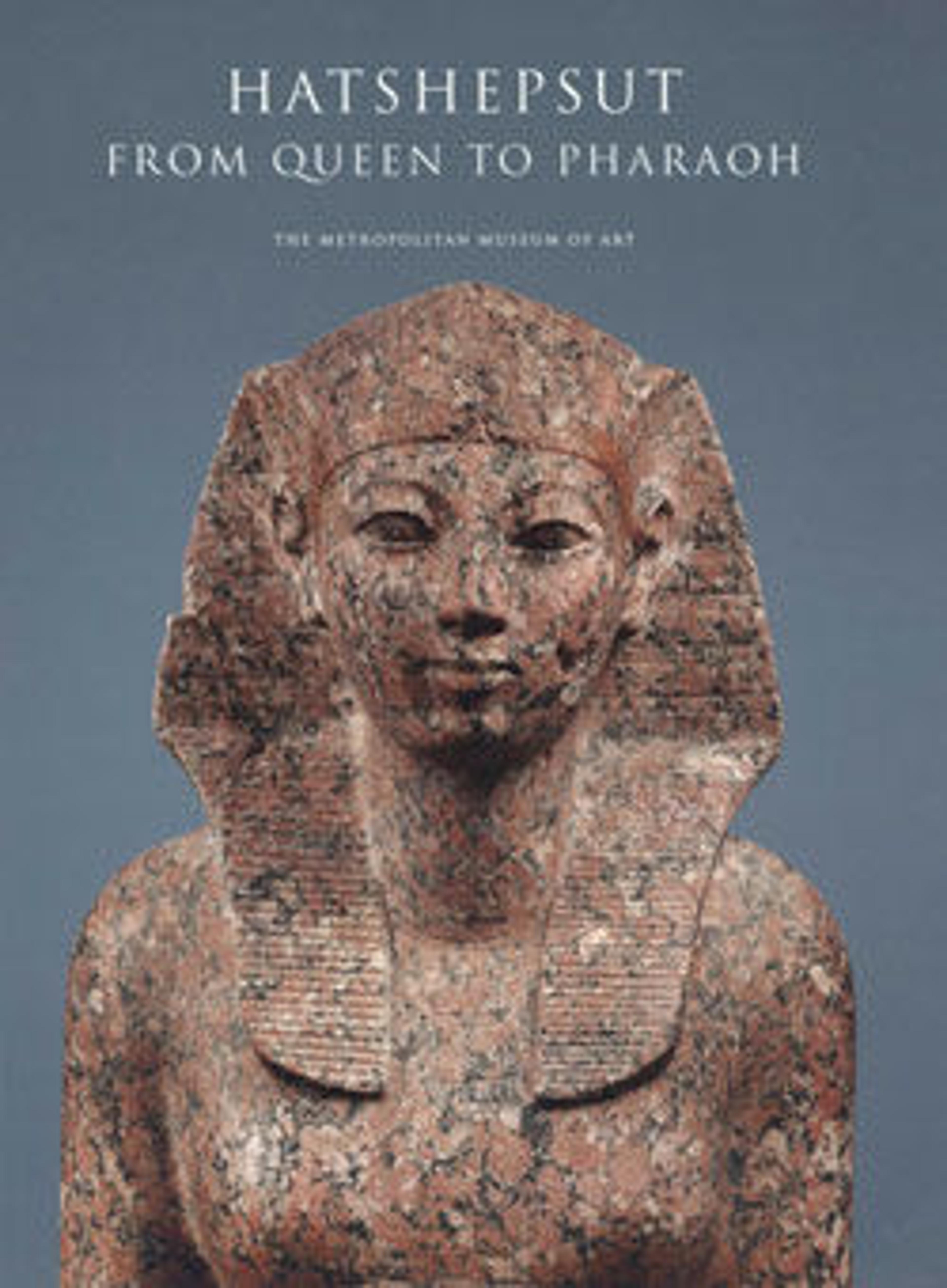

The pose of the statue, seated with hands flat on the knees, indicates that it was intended to receive offerings and it was probably placed in one of the Temple's chapels. In more public areas, such as the processional way into the temple, colossal sphinxes (31.3.166), kneeling (30.3.1) and standing statues (28.3.18) represent Hatshepsut as the ideal king, a young man in the prime of life. This does not mean that she was trying to fool anyone into thinking that she was a man. She was merely following traditions established more than 1500 years earlier. In fact, the inscriptions on the masculine statues include her personal name, Hatshepsut, which means "foremost of noble women," or a feminine grammatical form that indicates her gender. She had also been in the public eye since childhood, first as the daughter of king Thutmose I, then as principal wife of her half-brother Thutmose II, then as regent to her nephew/step-son Thutmose III, and finally as pharaoh. Only one other statue of Hatshepsut depicts here entirely as a woman (30.3.3).

In the early 1920s the Museum's Egyptian Expedition excavated numerous fragments of this statue near Hatshepsut's temple at Deir el-Bahri in western Thebes. The torso, however, had been found in 1869 and was in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden. In 1998, the Leiden torso and the MET's portions of the statue were reunited for the first time since the original was destroyed in about 1440 B.C.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Female Pharaoh Hatshepsut

- Period: New Kingdom

- Dynasty: Dynasty 18

- Reign: Joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III

- Date: ca. 1479–1458 B.C.

- Geography: From Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Senenmut Quarry, MMA excavations, 1926–29

- Medium: Granite

- Dimensions: H. 170 × W. 41 × D. 90 cm, 620.5 kg (66 15/16 × 16 1/8 × 35 7/16 in., 1368 lb.) (as reassembled)

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1929, Torso lent by Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden (L.1998.80)

- Object Number: 29.3.3

- Curatorial Department: Egyptian Art

Audio

807. The Female Pharaoh Hatshepsut

Look at the faces of the statues in this room. How many different people do you think they represent? Believe it or not, the answer is one. Well, all except the two small heads under glass. All of these sculptures show the pharaoh Hatshepsut, who lived about thirty five hundred years ago. In most of these statues, Hatshepsut appears as a muscular, powerful man. But on the platform, at one end of the gallery, there’s a smaller, reddish statue that shows the pharaoh as a woman.

In fact, Hatshepsut was one of only about three or four women ever to rule ancient Egypt—and she had a long and successful reign. She ascended the throne because her stepson, Thutmose the Third, became king when he was too young to rule. Later, he ruled with her, acting as a sort of junior partner—Hatshepsut held the real power. She ruled for more than twenty years. You may have noticed that these statues are made up of many pieces. We think that about twenty years after Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmose had her statues smashed. He also had her name erased everywhere it was written. His reason for doing this is still not completely clear. The Museum’s excavation team uncovered the pieces of these statues about seventy years ago. Most of the fragments were found near Hatshepsut’s funerary temple, which was originally with many, many images of her. Imagine trying to put together two dozen jigsaw puzzles when the pieces are all mixed together, and some are missing. And to make it even more difficult, some of the pieces are the size of your big toe, and others are so huge that they need a crane to move them into place.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.