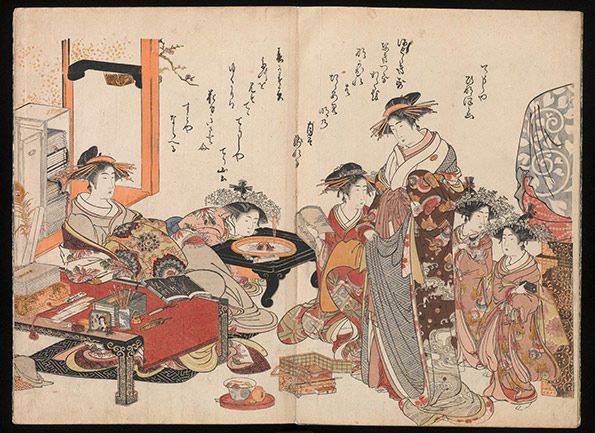

A New Record Comparing the Handwriting of the Courtesans of the Yoshiwara (Yoshiwara keisei shin bijin jihitsu kagami) 吉原傾城新美人自筆鏡

Kitao Masanobu (Santō Kyōden) 北尾政演 (山東京伝) Japanese

Not on view

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

Open Access

As part of the Met's Open Access policy, you can freely copy, modify and distribute this image, even for commercial purposes.

API

Public domain data for this object can also be accessed using the Met's Open Access API.

-

-

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/78670Link copied to clipboard

- Animal Crossing

-

- Download image

pages 7, 8

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.

Pages 1, 2. This preface is written by Yomo Sanjin (Ōta Nanpo; 1749–1823), a low-ranking samurai official who became a popular writer and poet of the day. The poems are inscribed in the courtesans’ own calligraphy, but most were originally composed by famous Japanese and Chinese poets of ancient times.

Pages 3, 4. This poem is signed “calligraphy by Hanamurasaki of the Kado-Tamaya.” As on the facing page, its subject is the beginning of spring. Waking up early to watch the rising sun on New Year’s day was a popular custom, and wealthy households would prepare feasts. A sign of abundance— over people’s homes in the morning, smoke from chimneys rises in the sky as spring begins. The Courtesan Komurasaki of the Kado-Tamaya Brothel look on as an apprentice courtesan examines rolls of fabric by candlelight. This poem is signed “calligraphy by Komurasaki of the Kado-Tamaya.” It addresses the traditional Japanese subject of risshun, or beginning of spring. Beginning of spring Last year remains in name only, as the trails of mist refuse to wait for the coming of spring.

Pages 5, 6. The Courtesan Azumaya of the Matsukaneya Brothel sits at a desk practicing a song on a shamisen, a three stringed musical instrument. Seated behind her is a shinzō, or teenage apprentice. At their feet, a child assistant is about to straighten her mistress’ geta sandals. With their bright sleeves glistening against the snow dappled ground, maidens must be gathering the new green herbs. The Courtesan Kokonoe of the Matsukaneya Brothel walks beside her assistant, who is carrying a tray with a lidded, lacquered bowl and a striped, ceramic brazier. Its pale green foliage announces spring, yet more welcome is the deeper green of the willow festooning eaves.

Pages 7, 8. The Courtesan Hinazuru stands at center before two kamuro, or child attendants, in spangled headpieces. A shinzō, or teenage apprentice, sits at left. As symbols of good fortune, flaming jewel motifs decorate the courtesan’s outer robe and those of her child attendants. She has copied out a poem by Fujiwara no Sanesada (1139–1191) from the celebrated compendium of court poetry called “One Hundred Poets One Poem Each” (Hyakunin isshu): When I turned to catch the source of the cuckoo’s call, all I saw was the moon in the early dawn sky. Chōzan, a courtesan of the Chōjiya Brothel sits at an elegantly appointed desk with brushes, poem cards, and books. Her child assistant blows on the coals in the hibachi, or container of hot coals. Chōzan has transcribed a poem by Lady Ise, included in the “Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern” (Kokin wakashū): Departing wild geese appear blind to the arrival of spring mists— is it because they harken from villages with no flowers?

Pages 9, 10. The Courtesan Hitomoto of the Daimonji Brothel sits reading poetry. Nearby, her child assistant holds a fukujusō plant, which blooms during the New Year season, and whose name literally means “plant of good luck and longevity.” Plum Blossoms Drenched in its fragrance merely by drawing close: each spring we await the first blossoming plum. The Courtesan Tagasode of the Daimonjiya Brothel wears an elaborate over-robe with a motif of a sickle and spring herbs on a black background. Spring in the Mountains Only the drip of thawing ice from the bamboo pipe tells the mountain village that spring has come.

Pages 11, 12. An attendant kneels with a shamisen, a three stringed instrument. On the banks of the Yoshino river the cherries blossom; as they scatter, they seem reflections of themselves. The Courtesan Utagawa of the Yotsubaya Brothel sits reading a letter at right. The Courtesan Nanasato stands, and prepares to inscribe a poem. As rain slants down, the fragrance of plum remains undiluted.

Pages 13, 14. In contrast to the bold Chinese cursive calligraphy of Segawa, the Courtesan Matsubito, of the some brothel, has transcribed a waka, or court poem, in a more delicate hand. She sits at right, displaying a box of kimono fabric. The work was originally composed by Ki no Tsurayuki, and included in the anthology he helped compile, “Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems” (Kokin wakashū): This glorious spring is woven from strands of green willow branches, as blossoms scatter after bursting at the seams. The Courtesan Segawa of the Matsubaya Brothel stands at left. Her two kamuro, or child apprentices, sit beside a container of hot coals to warm the evening. Segawa was known for her skills in calligraphy. Here she shows off both her refined education and elegant hand by inscribing a couplet from a Chinese poem of the Tang dynasty: The willow branch is snapped in the pleasure quarters. On a spring day, a courtesan is seen along the road.

Pages 15, 16. The Courtesan Takigawa of the Ōgiya Brothel strolls down the main avenue of the Yoshiwara District with her apprentice and two child assistants. Her pet cat joins them. In this case, the calligraphy reads from left to right. It begins with a line from a poem by Bo Juyi, the most popular Chinese poet in the ancient Heian court. The following waka, or court poem, is by Mibu no Tadamine. The spring breeze and spring waters Start to flow all at once… Just as soon as people say spring is here, this morning the mountains of lovely Yoshino are already veiled in mists. The Courtesan Hanaōgi of the Ōgiya Brothel follows Takigawa down the same avenue. At right, a wooden sign bears the name of the brothel and below are water buckets in case of fire. Hanaōgi inscribes two stanzas from a Tang poetry anthology: By their scent, you know the first blossoms have opened in Yoshiwara filling pockets and sleeves with fragrant plums.

Pages 17, 18. This colophon—written by Akera Kankō (1736–1799), a low-ranking samurai official and prominent man of letters—identifies the artist as Kitao Masanobu, better known by his pen name as a writer, Santō Kyōden. The colophon reveals that the the album was inspired by the Mirror of Yoshiwara Beauties (Seirō bijin awase sugata) published by Tsutaya Jūzaburō in the spring of 1776. That earlier book featured elegant depictions of courtesans by the prominent ukiyo-e artists Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1792) and Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1797).