Passage from “A Modern-Day Wen Xuan: Selections of Refined Literature”

Morikawa Kyoriku (Kyoroku) 森川許六 Japanese

Not on view

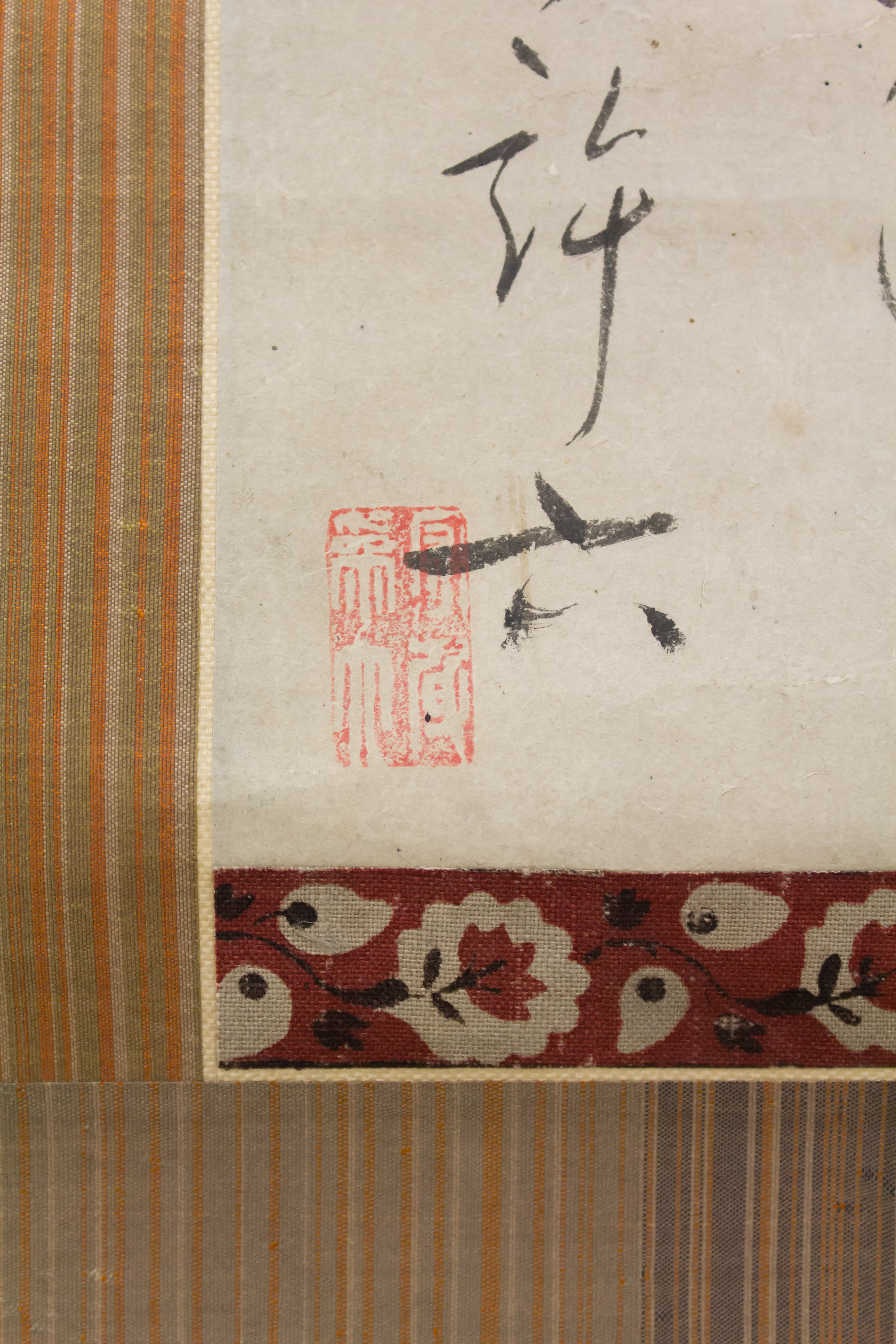

This hanging scroll records reflections on Japanese poetry by Morikawa Kyoriku, a samurai of the Hikone clan who was also a noted poet of haikai (seventeen-syllable verse) in the style of Matsu Bashō, and recognized as one of the master’s ten top pupils. The celebrated poet-calligrapher brushed seven columns of highly cursive, somewhat idiosyncratic, but eminently legible characters—mostly kana (Japanese phonetic writing) with an admixture of kanji (Chinese characters) that punctuate the composition with slightly denser forms. For instance, at the bottom of the second column from the right, we see the characters waka no michi 和哥の道, or the “way of Japanese poetry,” are melded into a column of mostly kana. And as we scan the text elsewhere for easily recognizable phrases, we realize that this is a prose commentary not on haikai, as we would expect, but on waka (courtly verse in thirty-one syllables) and the status of Japanese poetry in general.

Reading a few more phrases, we can see that the entire passage seems to riff off famous statements about waka included in the “Kana Preface” of the first imperially commissioned waka anthology, The Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern (Kokin wakashū, 905). In places it quotes verbatim from the “Kana Preface,” especially the famous phrase, “It is song that moves heaven and earth without effort, stirs emotions in the invisible spirits and gods, brings harmony to the relations between men and women, and calms the hearts of fierce warriors.” (Trans. Helen Craig McCullough). But Kyoriku injects a pessimistic note by commenting, “…That may be the case, but in this latter age, the primary obstacle to the way of Japanese poetry is money” (Saredo sue no yo ni atatte, waka no michi ni taisuru mono wa kane nari). The passage derives from the final section of the essay on “Vocabulary of the Four Seasons” (Shiki no kotoba 四季辞) from Kyoriku’s influential anthology of haibun (witty prose writings on literary topics), including passages by Bashō and his pupils, entitled A Modern-Day Wen Xuan: Selections of Refined Literature (Fūzoku monzen 風俗文選), which was published in 1705—providing a terminus post quem for this calligraphic excerpt.

The poet-calligrapher notes in his signature that he inscribed this hanging scroll while at his “retreat” (kankyo)—which we know from other sources was in Hikone City—on the eastern shore of Lake Biwa, to the northeast of Kyoto. Kyoriku does not tell us what inspired his little sketch, almost abstract in its simplicity, but we can safely assume that it was meant to depict one of the juxtapositions of rocks along a stone path found in the carefully tended “Fudaraku” (Potalaka) garden at Ryōtanji Zen temple, also in Hikone.

Kyoriku, who was also a skilled artist said to have been trained as a young man in the Kano atelier under Yasunobu (1614–1685), famously painted the sliding-door panels (fusuma-e) at Ryōtanji, still a popular tourist destination to this day. Interestingly, Kyoriku gave painting lessons to his poetry teacher Bashō at one point, and the great haikai master wrote to his pupil, “In painting you were my teacher; in poetry I taught you and you were my disciple. My teacher’s paintings are imbued with such profundity of spirit and executed with such marvelous dexterity that I could never approach their mysterious depths.” (Trans. Donald Keene, World within Walls, p. 139)

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.