Introduction

Winslow Homer (1836–1910) chronicled some of the most turbulent and transformative decades of American history. He developed his distinctive artistic vision in a crucible of struggle, creating emblematic paintings that illuminate the effects of the Civil War (1861–65) on soldiers, formerly enslaved people, and the landscape. Turning to charged depictions of rural life, heroic rescues, and churning seas, Homer continued to grapple with themes of mortality and the often-uneasy relationship between humans and the natural world. Close study of his art reveals a lifelong preoccupation with conflict and uncertainty as well as persistent concerns with race and the environment.

Homer’s iconic painting The Gulf Stream (1899, reworked by 1906), from The Met collection, is the inspiration for this exhibition. An allegory of human endurance amid the forces of nature, it also addresses the racial politics of the time and the imperialist ambitions of the United States. The Atlantic Ocean current of the title, visualized in the historical map at right, links many of the locales where the artist explored the central themes of his art—from the Caribbean up the Eastern Seaboard, and across the ocean to Europe. By reconsidering Homer’s dramatic pictures in the context of the Atlantic world, this exhibition encourages a deeper understanding of his full body of work, sophisticated artistry, and ability to distill challenging issues for diverse audiences, then and now.

War and Reconstruction

Homer launched his professional artistic career amid conflict—specifically, the moral and political crisis of the American Civil War (1861–65). He moved from early work as a popular illustrator in Boston and New York to the front lines in Virginia with the Union Army. There, as a “special artist” for the journal Harper’s Weekly, he documented the war and made struggle a central theme of his art.

Homer was fundamentally changed by the experience of war and carried its aftereffects throughout his career. Prioritizing oil painting over illustration, he probed the emotional and physical extremes of the conflict and its culture of death in a series of haunting subjects—from Sharpshooter (1863) to Prisoners from the Front (1866), the work that established his reputation as a painter of pathos. This culminating expression of the reunited country’s uncertain future pointed the way to equally penetrating representations of newly emancipated Black Americans in the South. In these works from the end of Reconstruction—marked by the final withdrawal of federal troops from the former Confederate states in 1877—Homer considered urgent questions of identity, labor, and citizenship, themes that also informed his depictions of White Americans in the 1870s.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Waterside

From 1867 until the mid-1880s, Homer maintained a studio in New York City. During an era of rapid urbanization, the artist chose to paint rural scenes instead of the bustle of city life. He followed travelers from different corners of society to resorts throughout the northeastern United States, from the Adirondack Mountains of New York to the beaches of Massachusetts. Homer may have been attracted to these locales for their pictorial splendor as well as their promise of solace, which he—and the nation—sorely needed after the trauma of wartime.

Homer often focused on the sea and shore as sites of leisure in the late 1860s and the 1870s. Inspired by an 1873 visit to the fishing village of Gloucester, Massachusetts, he conceived Breezing Up (1873–76), an optimistic image of men and boys at sea, a subject that would become a recurring motif in his work. In other oil paintings and watercolors of women and children near the coast, Homer considered humans’ relationship with nature. These seemingly lighthearted works also intimate darker themes, foreshadowing the artist’s growing preoccupation with the risks involved in maritime life.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Rescue

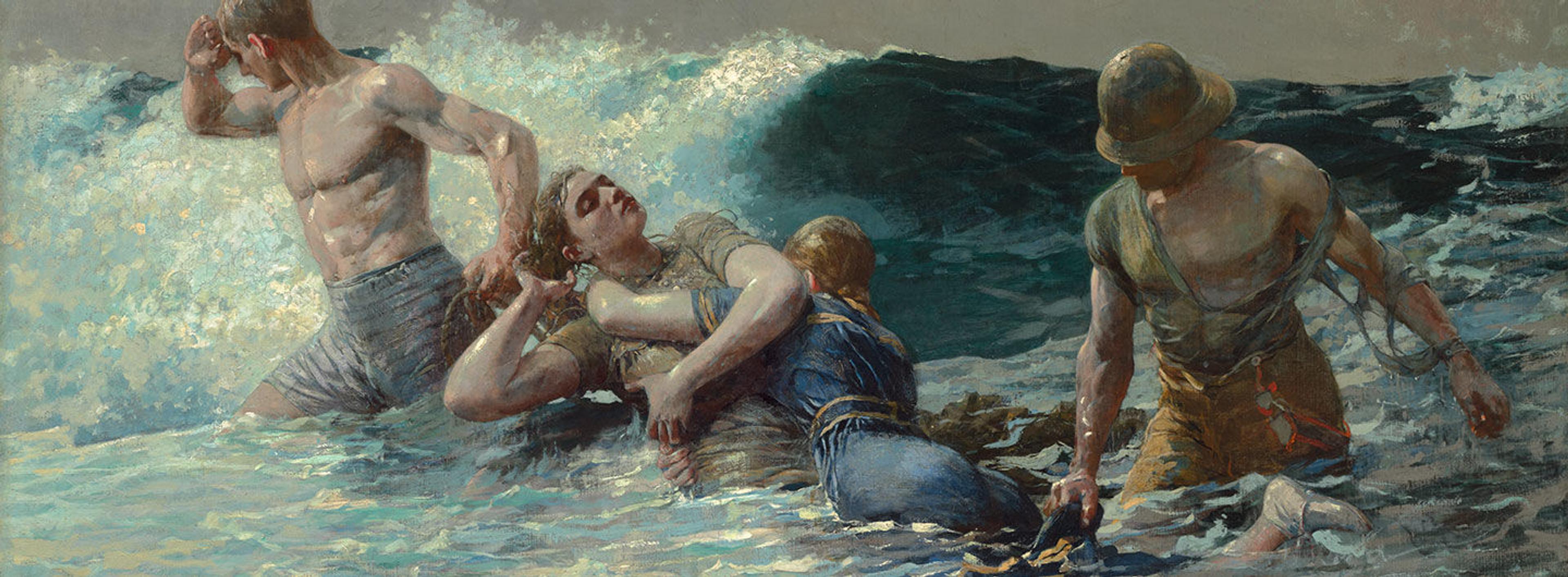

In the spring of 1881, Homer traveled to England. After briefly exploring London’s art collections, he settled in the North Sea fishing community of Cullercoats for a transformative residency. Inspired by the daily life-and-death experiences of local women and men inextricably tied to the ocean, the artist produced a number of dramatic oil paintings and watercolors focused on the subjects of danger and rescue.

Returning to the United States nineteen months later, Homer invested his art with a newfound gravitas and his figures with greater weight and feeling, as in The Life Line (1884). In his epic scenes of laboring fishermen in the North Atlantic—for example, The Fog Warning (1885)—the artist highlighted gender and class dimensions of sea peril, modern heroism, and human vulnerability in the face of the dynamic power of nature. Composed with pronounced tension and ambiguity, these works surface themes that would consume him for the rest of his career.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Along the Gulf Stream

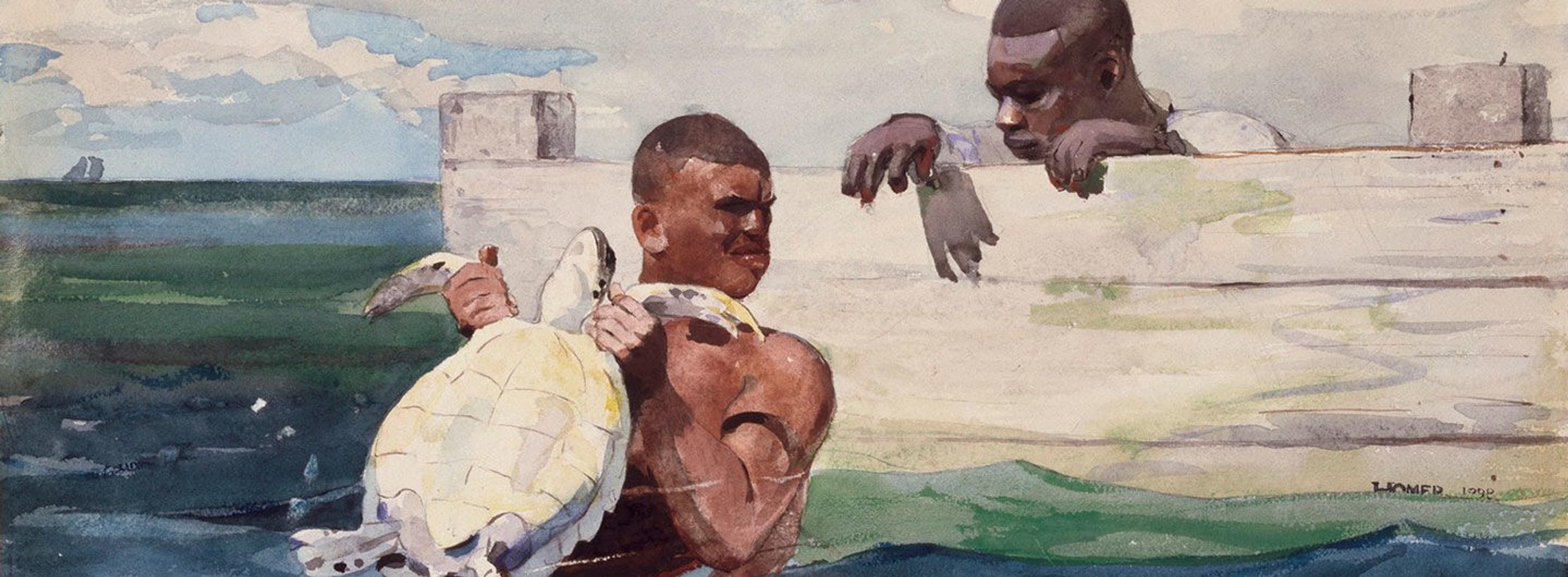

From the mid-1880s until his death in 1910, Homer often sought refuge from the harsh winters at his home in Prouts Neck, Maine, by traveling to tropical destinations. He visited the Bahamas, which he called “the best place I’ve found,” as well as Cuba, Florida, and Bermuda. During these trips Homer painted in watercolor, an ideal medium for representing the brilliant tropical light, sparkling blue water, dramatic changes in weather, and verdant foliage that captivated him.

Though contemporary viewers and critics admired the beauty and skill of these watercolors, they were deemed less significant than his oil paintings. One critic described them as “memoranda of travel—mere rapid studies and sketches, not complete pictures” and overlooked the significance of Homer’s subjects. In the Bahamas, the artist focused on the daily lives and labors of the islands’ Black inhabitants. During his stay in Cuba in 1885, he witnessed the ongoing struggle for independence from Spain and highlighted aspects of colonial history in his images. Similarly, Homer’s vibrant landscapes of Bermuda contain references to the British colonial presence on the island, including red-coated soldiers. These dazzling watercolors suggest a tropical paradise while also hinting at complicated imperial forces and natural threats.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The Gulf Stream

Initially inspired by Homer’s first trip to the Bahamas and Cuba in 1884–85, is an epic scene of conflict between humankind and nature. Conceived with great ambition and developed over more than twenty years—from the earliest sketch to the painting’s purchase by The Met in 1906—it is one of his most complicated and consequential works. The Gulf Stream has been understood variously as a personal reflection of Homer’s sense of isolation after the death of his father, and as a more universal rumination on mortality and the overwhelming power of the natural world—fundamental themes that the artist examined across his career. As Homer’s only major Caribbean seascape painted in oil and the only one to depict a Black figure, it also references complex social and political issues, including the legacy of slavery and imperialism in the wake of the 1898 Spanish-Cuban-American War. When Homer explained to a dealer that “the subject of this picture is comprised in its title,” he underscored his focus on the mighty Atlantic Ocean current, its larger ecosystem, and its historical significance. Homer used the Gulf Stream as the setting for many of his most powerful paintings.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Late Seascapes

After nearly a decade of living year-round in Prouts Neck, Maine, Homer recommitted himself to oil painting in the 1890s, making his studio view of coastal rocks and pounding surf his primary subject. Intent on capturing the changing mood and motion of the ocean in increasingly bold brushwork and keen detail, the artist foregrounded his subjective responses to the forces of nature and its profound mysteries. One critic marveled that Homer presented the “waves of the sea, as never before so studied, observed, suggested, and characterized.”

While canvases such as Winter Coast (1890) feature a negligible human presence, others like Northeaster (1895, reworked by 1901) were revised by the artist to focus exclusively on the physical environment, devoid of humanity. In these sensory and sublime seascapes, as well as a series of evocative moonlit images that suggest more symbolic meanings, Homer seems to reckon with the transcendent.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Mortality

The artistic themes of conflict and struggle that run throughout Homer’s career culminated in a series of works produced during his final decade. In dramatic scenes of hazardous family adventures in Quebec and more placid images of fishing and hunting in the Adirondacks, the artist confronted life and death in nature. Some compositions offer disquieting if traditional narratives of predator and prey. In others—such as Fox Hunt (1893) and Right and Left (1909)—Homer surprises with innovative depictions of Darwinian natural selection or environmental destruction that go beyond convention in their ambiguity of meaning. These images have been interpreted as autobiographical statements on mortality, painted by an artist who had directly confronted conflict and its consequences during his productive life.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Legacy

Homer believed that his watercolors were essential to his artistic legacy. In his writings, the artist acknowledged their critical role in the establishment of his reputation and in his ability to earn a living. Following Homer’s death in 1910, Kenyon Cox reflected on his fellow artist’s mastery of the medium, asserting that “in the end he painted better in watercolors . . . than almost any modern has been able to do.” Homer’s watercolors are celebrated for their technical brilliance, fluid immediacy, and striking, saturated tones. In them, the artist explored on a more intimate scale the powerful themes that preoccupied him across his career: epic scenes of distress on the ocean, conflict between humans and nature, and the transience of life.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.