Coins have been integrated into jewelry for thousands of years in many parts of the world and at all levels of society. Coin jewelry is found in Egypt, North Africa, and the rest of the Mediterranean, dating to as early as the Hellenistic period, and it was produced throughout the history of Byzantium. In this context, coins were used predominantly as pendants but also in the creation of bracelets, belts, and rings.

During Late Antiquity, gold coins, in particular, often received ornate framing devices, such as this fourth-century pendant from North Africa. Here, a medallion (double solidus) of Constantine the Great (r. 306–337) is set within a large frame that comprises elaborate gold openwork—a specialty of late antique goldsmiths—interspersed with gold busts sculpted in high-relief frames.

Circular pendant with double solidus of Constantine I, 370–390 CE. North Africa, Early Byzantine. Gold 3 3/4 in. x 3 1/2 in. (9 3/5 cm x 8 1/2 cm). Dumbarton Oaks BZ.1970.37.1-2

There were certainly less elaborate ways of adorning oneself with coins: humble bronze coins were simply pierced and strung, showing that wearing coins remained popular regardless of class. During Late Antiquity, coin jewelry appeared to have held universal appeal on account of two main features. The first was its ability to establish a connection between the wearer and the emperor. Once they were made into jewelry and worn against the body, the coins also functioned prophylactically and were thought to help protect the wearer against disease, misfortune, and evil spirits.

The Met’s gold pectoral with coins and a pseudo-medallion is one of the most intricate pieces of gold jewelry to survive from the mid-sixth century. The pectoral, worn around the neck, weighs an impressive three-quarters of a pound and consists of a hollow but rigid gold tube necklace attached to a complex gold frame that holds fourteen gold coins and two gold discs. Coins were manufactured in imperially-controlled mints. There, a metal flan would be placed between two dies engraved with the obverse and reverse coin designs. This was then struck by a hammer, impressing the design on the coin. (These dies do not survive because once a run of coins was produced, the die was intentionally destroyed to avoid counterfeits.) The larger gold pseudo-medallion at the pectoral’s center imitated the style and iconography of officially struck coins but was unofficial and manufactured completely differently. In no way was it trying to deceive about its economic value; rather, its aim was to make symbolic associations to contemporary coinage.

Pectoral with coins and pseudo-medallion, ca. 539–50 CE. Egyptian, Byzantine. Gold, 9 1/2 x 8 5/8 x 5/8 in. (23.9 x 21.9 x 1.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.1664)

The coins in the pectoral date from the fourth to the sixth centuries, with the latest coins minted in the period of Justinian (r. 527–65). Therefore, the person who commissioned this pectoral had amassed a collection of coins spanning over two hundred years of history, likely through familial bequest. Today, it is possible to acquire a coin dating to the American Revolution, but how many people can say that a coin dated to 1776 has been in their family continuously for close to 250 years?

Imperial Connections

In Byzantium, coin value corresponded to weight, and just as today, the state tightly controlled coin production. Starting in the fourth century CE, the dominant gold coinage was the solidus, which weighed about 4.5 grams. The pectoral holds twelve solidi and two tremissis coins, valued at about a third of a solidus. Both the solidus and tremissis coins would have circulated in the economy but were rarer, as bronze or silver coinage was more common.

Medallion, consisting of a coin of Theodosius I, 379-395 CE. Istanbul, Turkey, Byzantine. Gold, Diam (overall): 0.5 cm (1/8 in). Gift of Charles Lang Freer, Freer Gallery of Art, F1909.67

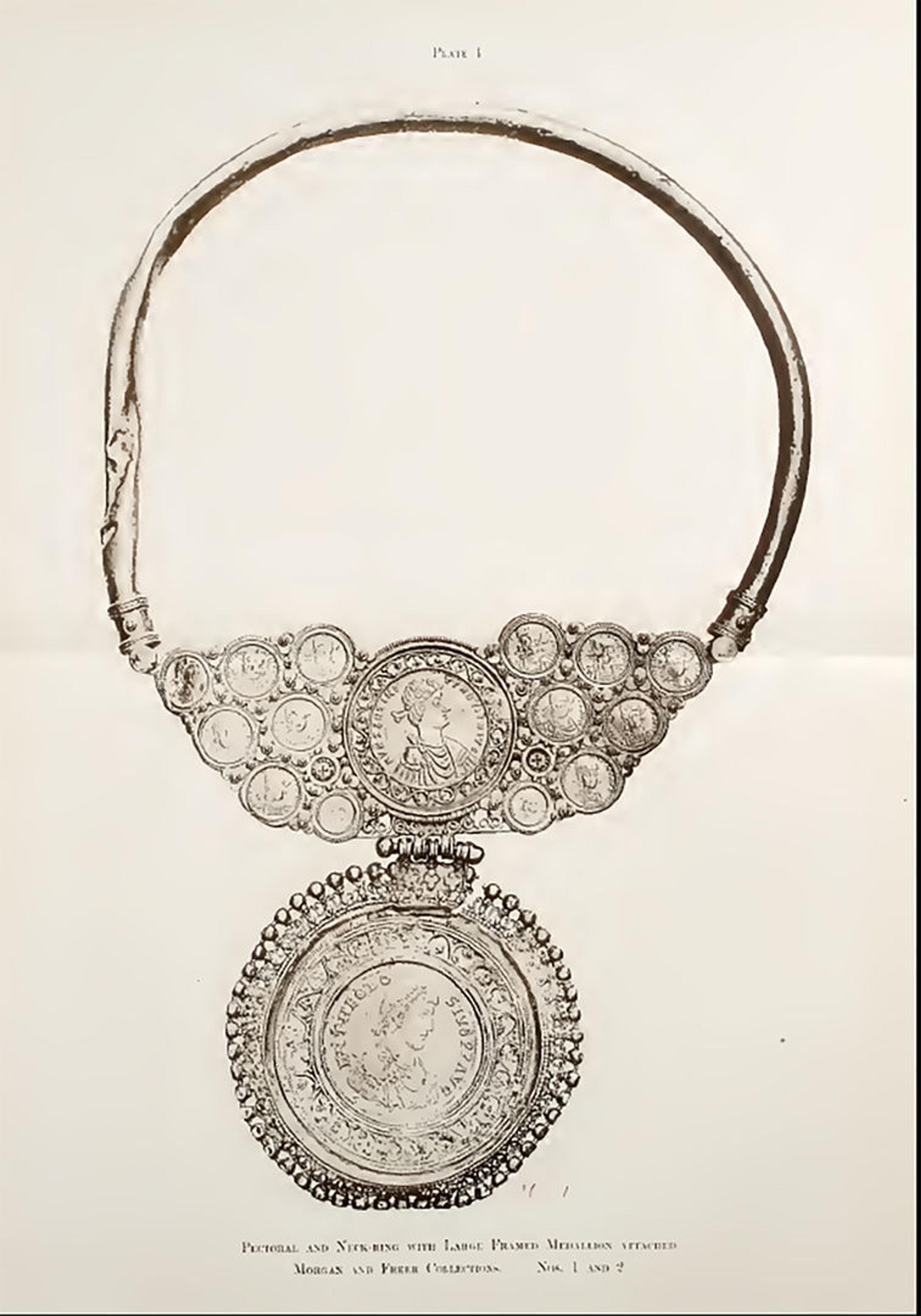

Originally, a large, framed fourth-century medallion of the emperor Theodosius I, now in the Freer Gallery of the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art, was attached to The Met’s pectoral via the ribbed rings seen at the bottom of the piece. Unlike the large pseudo-medallion at the center of The Met’s pectoral, the Freer piece has an officially struck medallion. Medallions correspond in weight to a multiple of two or more solidi. In terms of appearance, they had many shared characteristics with solidi, but they did not circulate in the normal economy. Emperors issued these multiples to commemorate special occasions, such as anniversaries, births, and deaths; individuals with affiliations to the imperial court were then gifted medallions. The inclusion of a an officially struck medallion attachment on The Met’s pectoral suggests that this pectoral belonged to not just a wealthy individual but to someone with imperial ties.

Girdle with coins and medallions, ca. 583 CE, reassembled after discovery. Byzantine, Found at Karavas, near Kyrenia, Cyprus. Gold, 26 1/2 x 2 1/4 x 1/4 in. (67.5 x 5.5 x 0.6 cm) Wt: 348g. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917; Purchase, Morgan Guaranty Trust Company of New York, Stephen K. Scher and Mrs. Maxime L. Hermanos Gifts, Rogers Fund, and funds from various donors, 1991 (17.190.147; 1991.136)

Despite the rarity of medallions overall, proportionally to other coins, they are frequently discovered embedded within the most exceptional pieces of surviving coin jewelry. In addition to the Freer and Dumbarton Oaks pendants, this girdle in The Met’s collection comprises four gold medallions depicting the emperor Maurice Tiberius (r. 582–602) linked to various other gold solidi.

Plate 1 from Walter Dennison’s, A Gold Treasure of the Late Roman Period (New York: Macmillan, 1918), showing Met Pectoral and Freer Gallery together.

Unlike the Freer medallion, the large pseudo-medallion at the center of The Met’s pectoral was not minted in a state-controlled facility; it imitates the style and iconography of sixth-century medallions. We know this because of its production technique, which included puncturing and chiseling, rather than the stamping technique used to make coins and official medallions. On the front (obverse) of the pseudo-medallion is an emperor shown in profile wearing a diadem, cuirass, and military cloak fastened with an elaborate brooch. The inscription that frames the bust is illegible yet seems to imitate common inscriptions on coins. The reverse depicts a seated personification of a city, holding a scepter in her left hand, a globe with a mounted cross, and a Chi-Rho symbol of Christ to the left. This imagery is surrounded by another inscription comprising letters that do not form any words. The pectoral serves as a symbol of wealth and elite status. When originally attached to the Freer medallion, the pectoral also makes the wearer’s explicit imperial associations visible.

Back and front of Pectoral with coins and pseudo-medallion, ca. 539–50 CE. Egyptian, Byzantine. Gold, 9 1/2 x 8 5/8 x 5/8 in. (23.9 x 21.9 x 1.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.1664)

“Lord, Protect the Wearer”

In addition to the worldly associations the pectoral owner was trying to make, in terms of establishing an imperial connection, the design of this coin jewelry suggests that it was intended to perform additional functions. When the pectoral was worn against the body, the viewer would see the obverse of all the coins, meaning the imperial portraits on the coins were visible. Imperial portraits, in the context of Late Antiquity, could serve as direct links to the emperor himself. In fact, the real emperor and a representation of an emperor were meant to be treated analogously. Portraits of emperors became more generic over time, speaking to the idea that they were the image of the emperor rather than a mimetic portrait of a specific emperor. By displaying this group of imperial portraits around their neck, the owner of this pectoral was explicitly invoking the emperor’s protection.

In a text instructing catechumens (individuals who are in the process of converting to Christianity but are not yet baptized), the late-fourth-century church official John Chrysostom criticizes the wearing of coins as charms and protective amulets. Surviving material evidence substantiates that people in Late Antiquity believed that once coins had been turned into jewelry, they possessed prophylactic value. For example, a surviving pierced bronze coin of Justinian I bears a Greek inscription, which translates to “Lord Protect the Wearer.”

In addition to this modest example, the same inscription appears on both the obverse and reverse of another gold pseudo-medallion, which sits at the center of a gold pectoral in the Antikesammlung of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. In this pectoral, which closely resembles the one at The Met, fourteen coins (twelve solidi and two tremissis coins), along with two gold discs, frame a pseudo-medallion, and a framed gold medallion hangs from the bottom. The hanging medallion is decorated on both sides with Christian imagery: iconography of the Annunciation appears on the obverse and the Marriage at Cana on the reverse. Despite Chyrsostom’s admonishments, these objects attest to the continued Christian use of coins prophylactically.

Pectoral with coins, pseudo-medallion, and hanging “medallion” showing the Annunciation to Mary and the Marriage at Cana, mid-fifth century or later. Egyptian, Byzantine. Gold, Diameter: 23.5 cm. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Ident. Nr.: 30219, 506

Identity of the Owner

In a sixth-century icon from Mount Sinai, now in Kyiv, the martyred military saints Sergius and Bacchus both wear rigid gold neck rings like the one supporting the set coins in the pectoral, but here they frame set gems. Members of the emperor’s bodyguard are also depicted wearing similar rigid gold neck rings with attached large-scale pendants in the mosaic of the emperor Justinian in the apse of San Vitale in Ravenna. Both representations point to such pectorals as the one in The Met as being worn by military men.

Right: Icon with Saints Sergius and Bacchus, mid-seventh century. From Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai, Egypt. Encaustic painting on wood panel. © Khanenko Museum Kyiv, Ukraine; courtesy Musée du Louvre. Left: Emperor Justinian and Members of his Court, mosaic in the apse wall, San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy, 526–48 CE. Photo Wikimedia Commons

Scholars have also noted that the inscription on both sides of the pseudo-medallion in the Berlin pectoral is written in the feminine, potentially suggesting a female wearer. Coin jewelry was often the result of generations of collecting, so the owner could have changed over time, or individuals might have held it for extended periods. Archaeologists discovered a pierced third-century coin of Marcus Aurelius in a house that wasn’t abandoned until the seventh century in Anemurium, Turkey, suggesting it had been worn for centuries by numerous individuals.

Throughout the early Byzantine Empire, whether in Constantinople or Upper Egypt, dress was an expression of status, and jewelry was a key aspect of this signification system. A direct correlation can be traced between the amount of ornamentation on dress and jewelry and the wearer’s social status. Beyond its capacity to demonstrate wealth and status, individuals believed that coin jewelry could protect them through supernatural powers. The Met’s gold pectoral appears to have performed both roles, asserting the wearer’s elite status and direct connection to the imperial court while simultaneously protecting against misfortune.