How does a good artist become a great one? In Man Ray’s case there’s no one better to ask than Kiki de Montparnasse (1901–1953), who lived and worked alongside him in Paris for most of the 1920s, a decade of miracles when after much crouching, watching, and waiting in New York, he finally uncoiled and struck—again and again—creating the bulk of his most innovative and enduring works in a tight span of years. Kiki’s answer? “He made his best photos with me, he understood my body, my type. In the end, me, the model—I was the one who gave him his genius.”

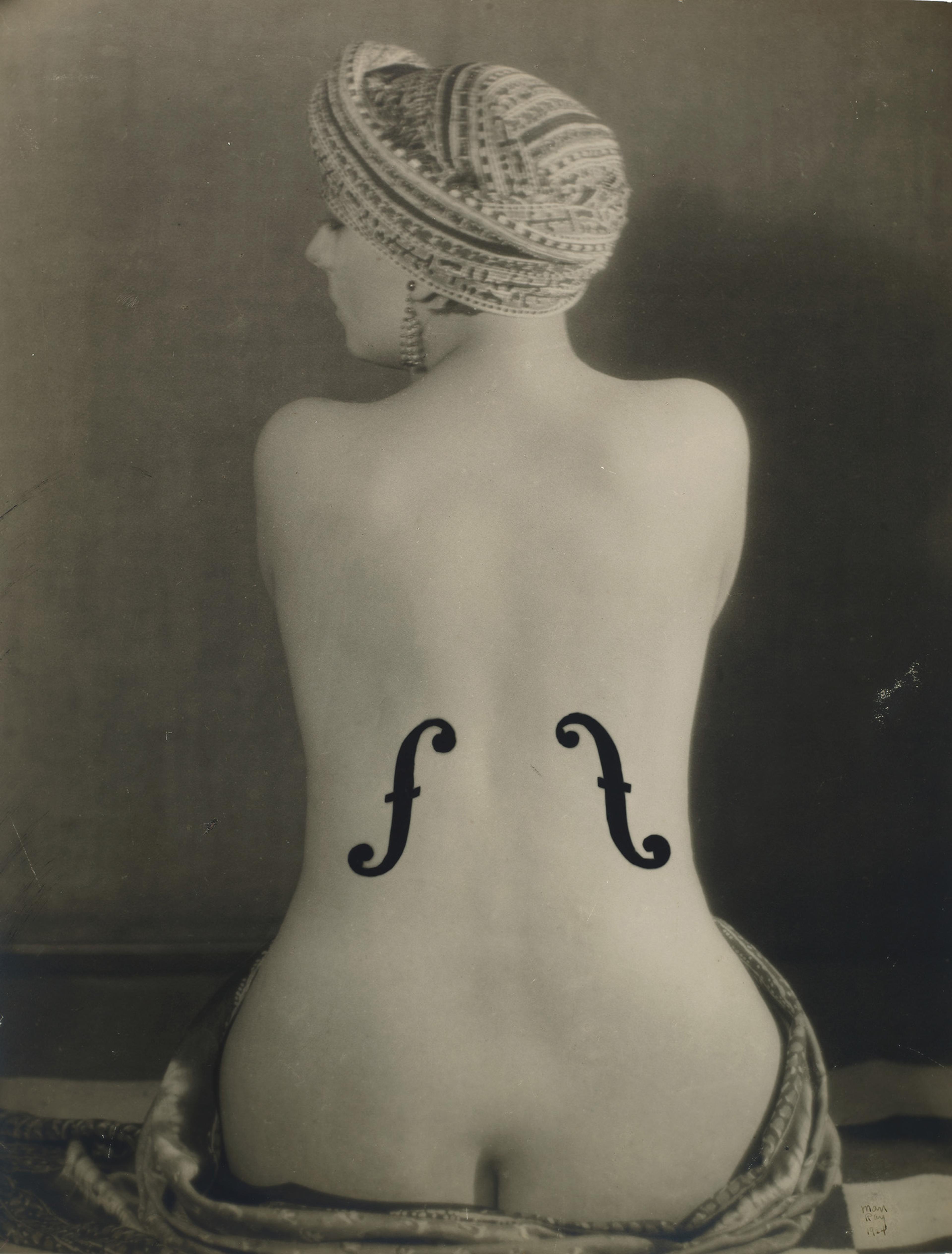

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Le violon d’Ingres, 1924. Gelatin silver print, 19 × 14 3/4 in. (48.3 × 37.5 cm). Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Before laughing off that claim, we might instead dig for the truth she’s hidden beneath her hyperbole. Man Ray’s vision was already maturing quickly by the time he came to Paris, filled with heady rhetoric from Marcel Duchamp about creating art that would please the mind as much as the retina. But only once his life became romantically and artistically entwined with Kiki’s did he grasp how to put those ideas into practice—both by expanding that vision, experimenting in various media, and by crystallizing it into several exceptional images, moving and still, that are at once mysterious, unsettling, and quizzical, as well as gorgeous to behold. And more than anyone else, by a long margin, during those years of finding his way with his secondhand camera, he experimented with Kiki. She didn’t “give” Man Ray his genius, but she certainly helped to unleash it.

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Noire et blanche, 1926. Gelatin silver print, 8 1/16 × 11 11/16 in. (20.5 × 29.7 cm). Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

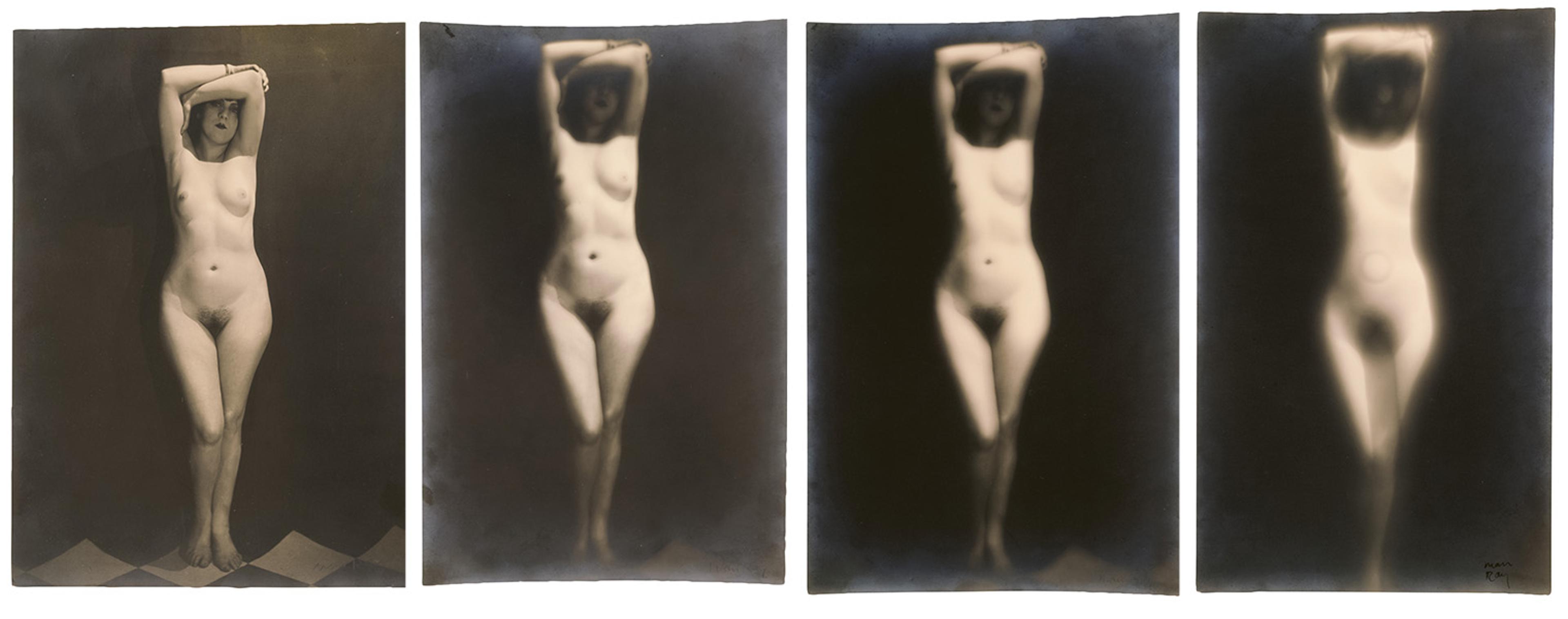

The hundreds of images they produced over that decade trace a definitive shift in Man Ray’s approach. The severity of his initial attempts, marked by Kiki’s stiff, unnatural posing and theatrical costuming gave way to scenes that, while still highly polished and carefully orchestrated, are somehow far wilder, stranger, more playful—and also more dangerous. These images improved as their relationship deepened and then imploded, as they became both more open with and more antagonistic toward one another, as the wounds and resentments accumulated alongside the shared joys and discoveries.

Must we take Kiki at her word that only Man Ray could understand “her body, her type,” which helped him achieve his singular vision? Some in their circle would say yes. André Breton (1896–1966) in his essay “Man Ray” decided that women like Kiki were interchangeable objects in service to the master behind the camera, and who, worse still, didn’t even register how interchangeable they were. “The very beautiful women who expose their tresses night and day to the fierce lights in Man Ray’s studio are certainly not aware that they are taking part in any kind of demonstration,” he wrote. “How astonished they would be if I told them that they are participating for exactly the same reasons as a quartz gun, a bunch of keys, hoar-frost or fern!”

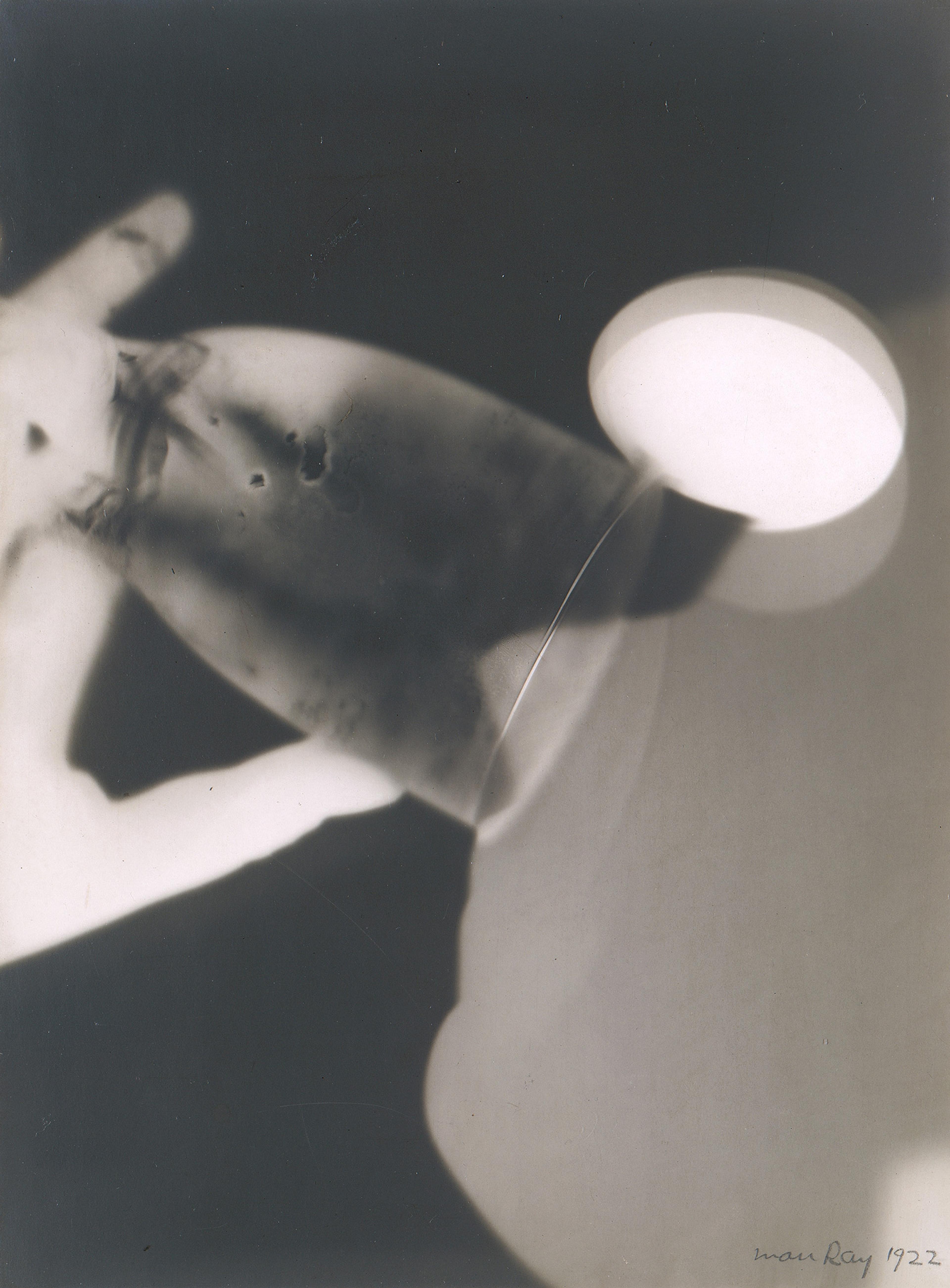

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Rayograph, 1922. Gelatin silver print, 9 7/16 x 7 in. (23.9 x 17.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005 (2005.100.139). © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Others suggested that Man Ray’s genius was so all-encompassing that he not only used Kiki’s body to make art but turned that body itself into one more art object. The novelist Kay Boyle (1902–1992), spreading a nonsensical rumor that Man Ray applied Kiki’s elaborate makeup for her each morning, wrote of how Man Ray “designed Kiki's face for her, and painted it on with his own hand.” Peggy Guggenheim repeated the story, dubbing the duo “Man Ray and his remarkable hand-painted Kiki.” Of all people, it was Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) who gave Kiki the most autonomy when it came to her makeup, writing in his introduction to Kiki’s memoirs that “having a fine face to start with she had made it a work of art.”

On the other hand, there were those like Tsuguharu Foujita (1886–1968), another close friend of the pair, whose wondrous portrait of a lounging Kiki in 1922 made his name with the French public, and who deemed her an active collaborator in its creation. They’d interrogated and examined one another over several sessions in his Montparnasse studio, a mutually enlightening process of dancing, eating, laughing, and experimentation, including, at one point, switching places, with Foujita experiencing what it felt like to pose as Kiki drew him. Foujita wrote that “Kiki and I were equally happy” with the finished work and that “neither of us could say for sure who among the two of us was its author.” He put his money where his mouth was, sharing the large proceeds from the painting’s sale with Kiki.

While Djuna Barnes (1892–1982), in a 1924 magazine piece about Kiki, wrote that Man Ray gave Kiki “credit for one his best marines” when “she stormed into the room, so dark, so bizarre, so perfidiously willful … that in a flash he became possessed of the knowledge of all unruly nature,” the anecdote rings too good to be true, and there’s no evidence of said seascape. Man Ray actually left no record of how he felt about Kiki’s influence on his art. He did write about Kiki’s own art-making in his autobiography, only to dismiss her creative pursuits as mere diversions, her way to solve the problem of passing time, “which hung heavily in her hands” and kept her from her domestic calling. Yet he also carefully saved decades-old clippings from Kiki’s 1927 gallery debut of her paintings (in fact, a sold-out show), as well as boxes and boxes of negatives from their time together, including dozens of shots documenting her paintings and drawings.

When examining Man Ray’s photographs and films of Kiki, it is essential to understand that she was the performer of the pair, someone we would today call a “multi-hyphenate.” Already a sought-after model when they met, soon to become a beguiling and beloved cabaret performer and eventually screen actress, as well as a painter and writer, she knew how to seduce a crowd and a camera. She could turn herself into a story meant for public consumption. Look at the images they made together as if they were little pieces of theater, and see if you’re willing to ascribe the actor with as much power in making these performances shine as their director.

Left to right: Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Kiki de Montparnasse, 1924. Gelatin silver print, 8 7/8 × 6 5/8 in. (22.5 × 16.8 cm). Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Kiki de Montparnasse, 1924. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/8 × 7 3/8 in. (28.3 × 18.7 cm). Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Kiki de Montparnasse, 1924. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/8 × 7 3/8 in. (28.3 × 18.7 cm). Kiki de Montparnasse, 1924. Gelatin silver print, 10 3/8 × 6 13/16 in. (26.4 × 17.3 cm). All images Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

As Man Ray practiced his craft with Kiki, through countless different scenarios, states of dress and undress, and poses and positions, she helped him with a patience that can only come from love. They were young together, both finding their own ways to give voice to how they felt about themselves and their world, when everything was still ahead of them, when they were still unsure of their talents and nothing had been locked in. And yet there was not only love and patience between them. They had a volatile connection, carnal, dark, violent, and abusive. They were rivals as much as they were friends, perhaps more so. If Kiki inspired new work from Man Ray, she did so in part by creating her own. Less hung up on outward markers of success, she lived with a freedom that he knew he would never attain. “All I need is an onion, a bit of bread, and a bottle of wine,” she liked to say. She had little time for intellectualizing art, and their divergent approaches to achieving a creative life apparently caused much of the difficulty between them. How much one chooses to see that difficult dynamic translating into the many pictures they made together, equal parts tender and menacing, is up to the viewer.

In the end, we have only the images. And the question: can you imagine them working their same rough magic if someone else, some interchangeable stranger, was their subject?