When Lee Miller (1907–1977) arrived in Paris in 1929, she had rejected a painting career and had “given up art.” Prior to this, she had been a student at the Art Students League in New York, and after a short spell in Florence studying and drawing from paintings by Italian masters, declared that as far as she was concerned “all the paintings had been painted,” and thus she turned to photography.

Miller’s photography background up to this point was from her father, a skilled amateur whose main interest was stereoscopic imagery. Having worked as a model in New York, she also gleaned knowledge of the medium while posing for Edward Steichen (1879–1973), whom she had known since she was a child, and for other fashion photographers of the day.

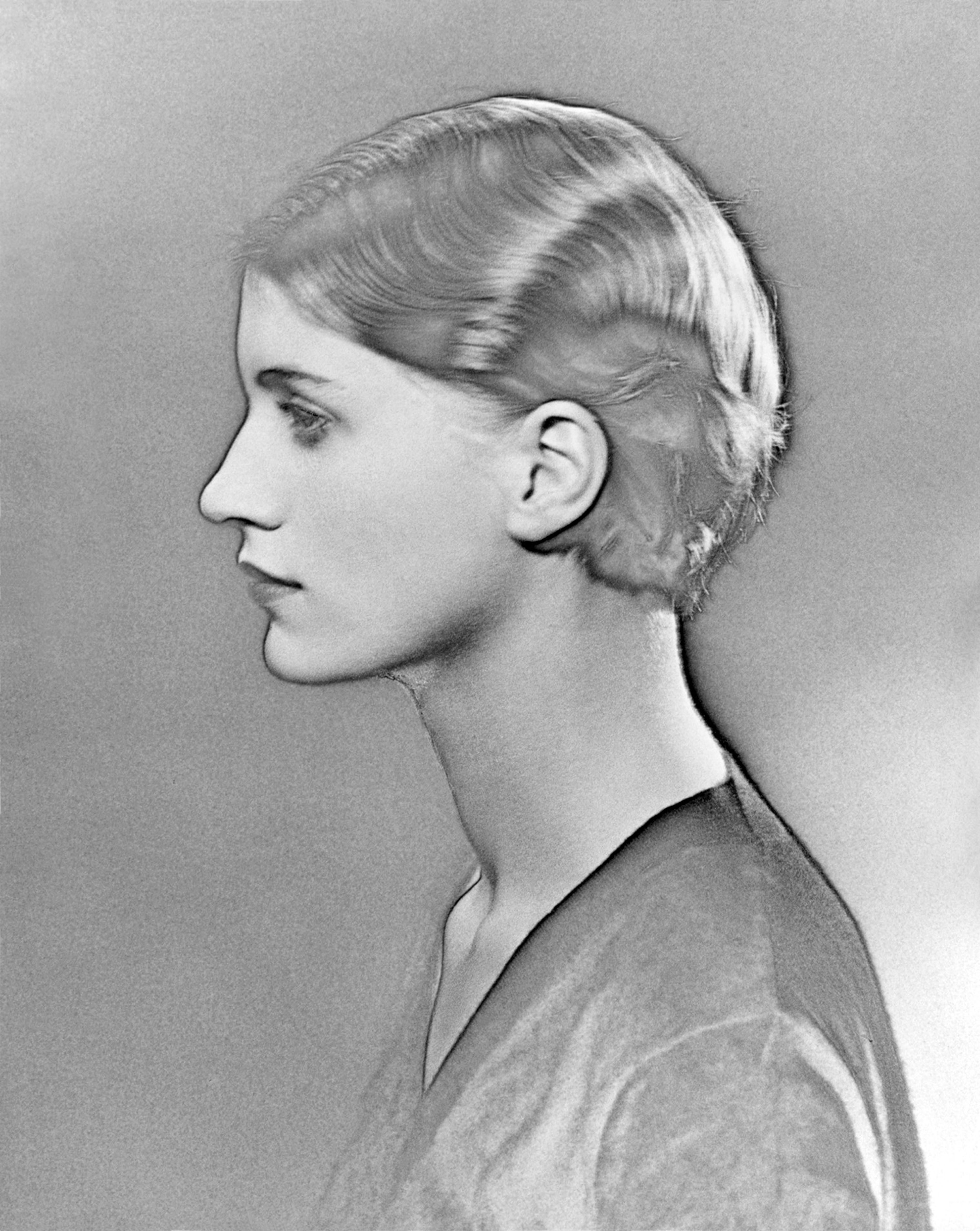

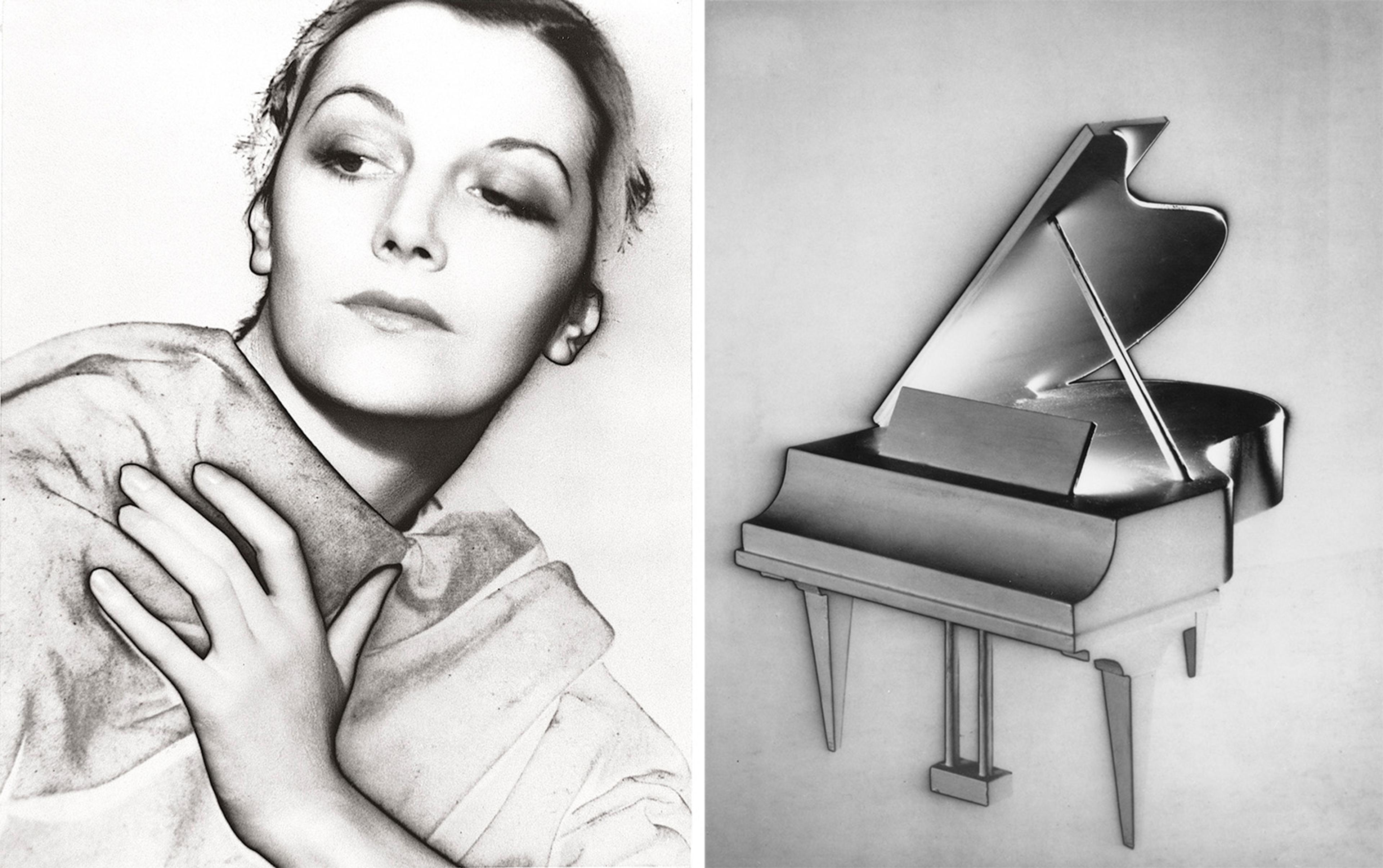

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Lee Miller, 1929. Gelatin silver print, 10 1/2 × 8 1/8 in. (26.7 × 20.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of James Thrall Soby (148.1941)

Her plan to seek out Man Ray in Paris was a calculated risk; she had the promise of modeling work for George Hoyningen-Huene (1900–1968) at French Vogue as a safety net. (In fact, she continued to model part-time to supplement her income until mid-1931.) Although Man Ray had other students, he initially refused Lee, but the combination of a letter of introduction from Steichen and Miller’s determination changed his mind.

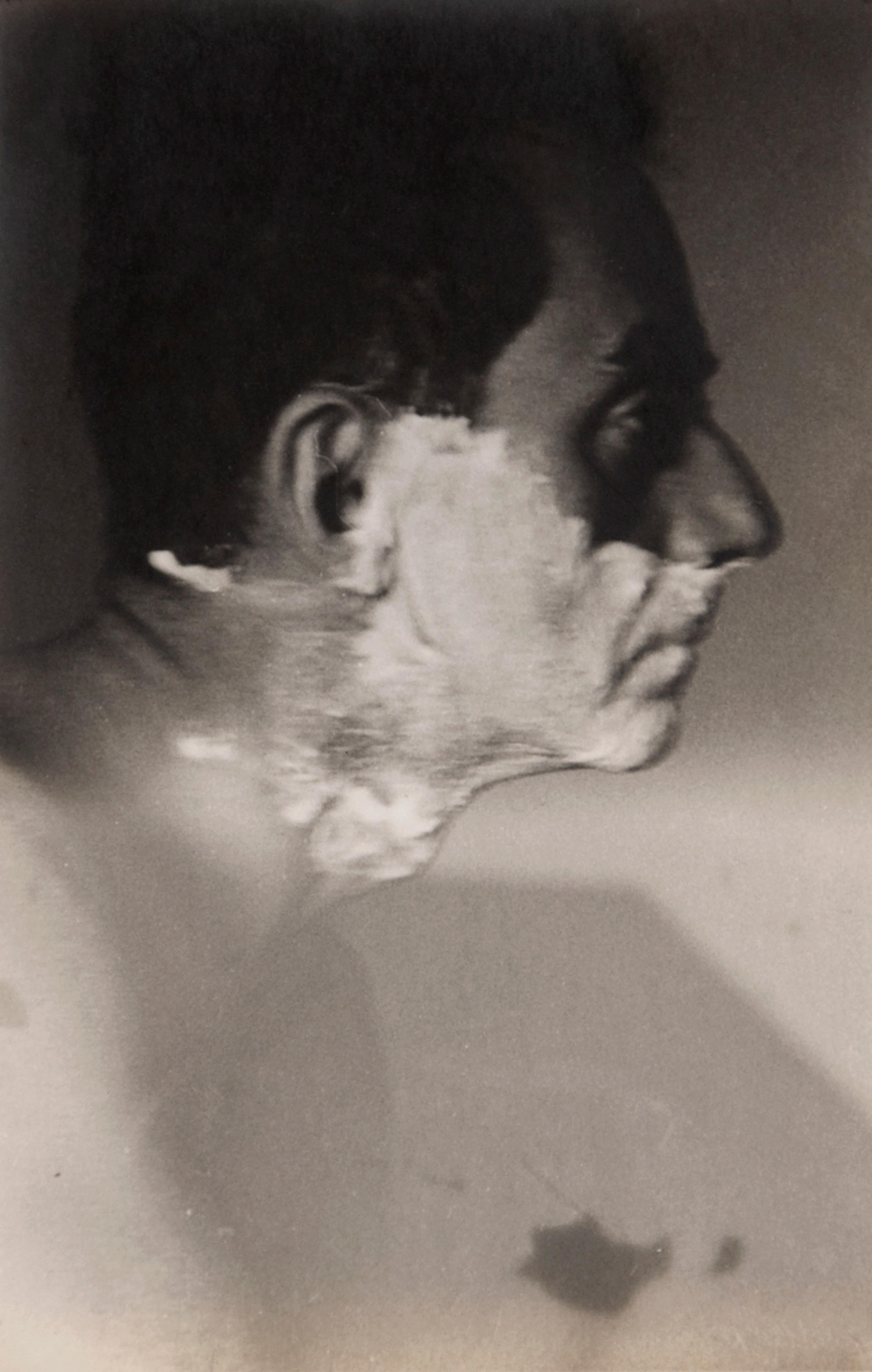

Lee Miller (American, 1907–1977). Man Ray Shaving, ca. 1929. Gelatin silver print, 12.3 x 7.7 in. (31.2 × 19.5 cm). © Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved.

Miller’s apprenticeship with Man Ray is often misrepresented as being the entire period that she was in Paris, between July 1929 and October 1932. However, she considered it to be only the first nine months—after which they worked together as equals, inspiring and supporting each other in their objectives.

Although Miller and Man Ray worked intensively and quickly became lovers, Miller maintained her independence despite a seventeen-year age gap. By July 1930, she was living in and running her own photography studio at 12 rue Victor Considérant, near the Montparnasse Cemetery. It was an apartment with a mezzanine level covering over half the space; she used part of it as her studio and converted the kitchen so she could develop prints there. She also used Man Ray’s studio for her own shoots, though she described his darkroom as being no bigger than “a bathroom rug.”

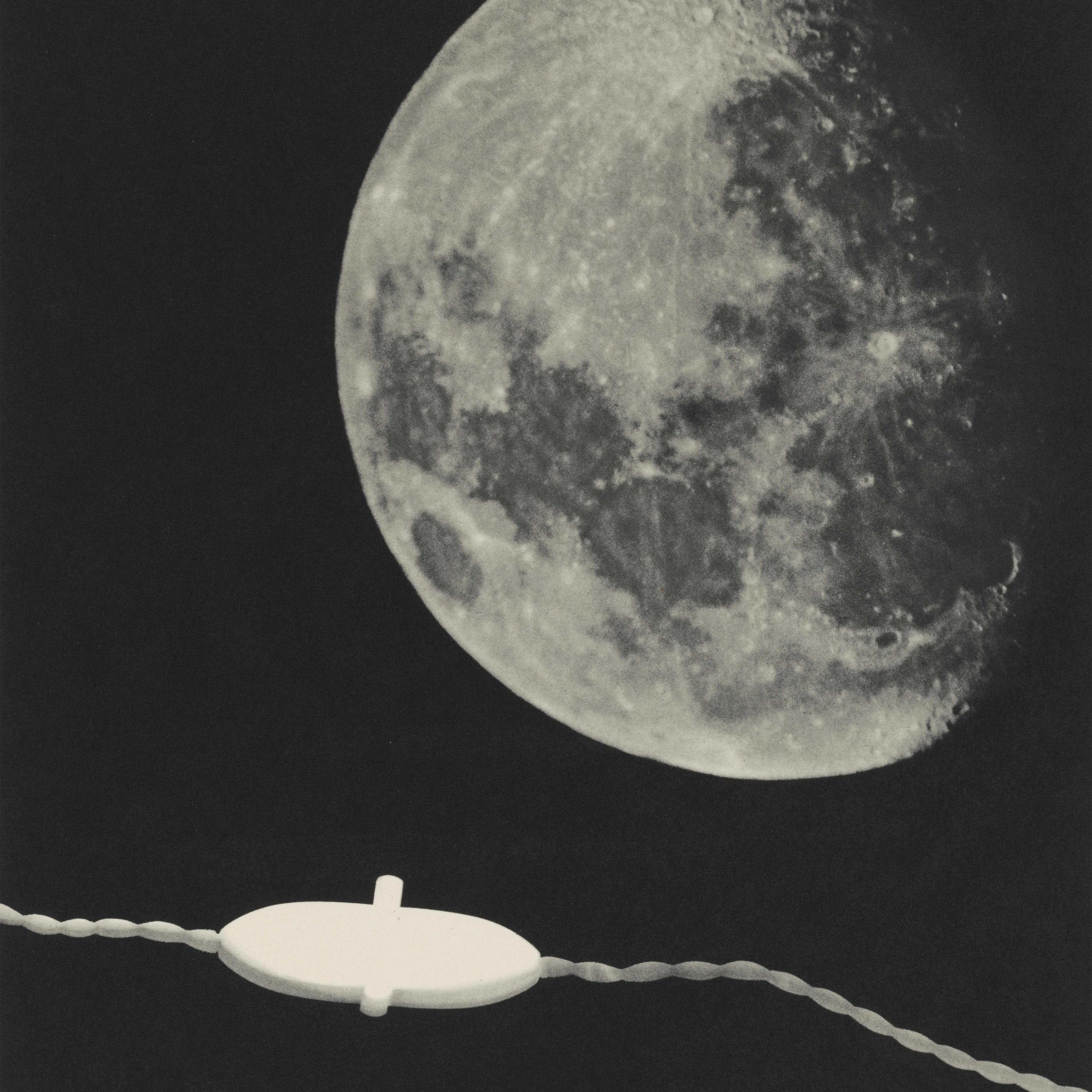

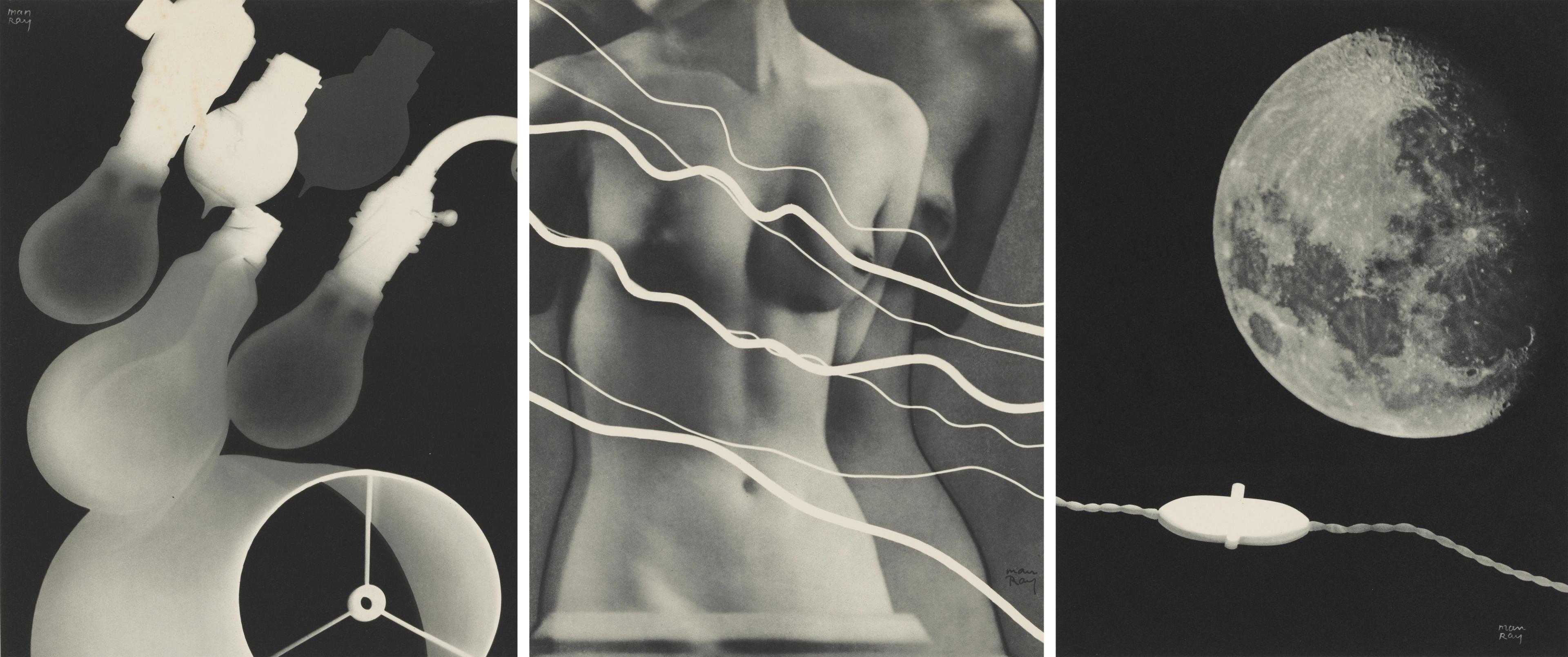

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Three photographs from the Électricité portfolio, 1931. Portfolio of ten photogravures. Cover: 15 × 11 1⁄2 in. (38.1 × 29.2 cm) Each image (approx.): 10 1⁄4 × 8 in. (26 × 20.3 cm) Each mount: 14 13⁄16 × 10 7⁄8 in. (37.6 × 27.7 cm). The Penrose Collection. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

One example of their collaboration is her accidental rediscovery in the darkroom of the photographic phenomenon called the Sabattier effect (a second exposure of the negative or print during the development process), which she shared with Man Ray. After perfecting it together, Man Ray named it “solarization.” Both photographers used the technique in their work from this point on. Another is their close partnership on the Électricité portfolio, which a Paris-based electricity company commissioned Man Ray to produce in 1931. The portfolio was an edition of five hundred copies, each containing ten images that celebrated electricity. Miller helped with the ideas behind many of the photos. The final ten works used different techniques, mostly photograms (rayographs) and a solarized image printed as photogravures. Aware that he would receive all the credit, Man Ray inscribed in Lee’s copy: “To Lee Miller, without your enthusiasm and without your aid this album would not have been possible, gratefully, Man Ray.” Despite Man Ray’s intentions, Lee’s contributions are unfortunately still often overlooked today.

Man Ray’s relationship with painting was quite the opposite of Miller’s. She stated in later interviews that within less than a year of starting to work with Man Ray, she was doing the majority of his photography work for him because he wanted to focus on painting. Before that, he gave her jobs that he didn’t want or that didn’t pay much. It was Miller who suggested that she take on all of his photography work. This meant that his commissions between 1930 and 1932 were undertaken mainly by Miller yet published under his name so that they could still collect payment for the work. At the time, she didn’t care about her work being attributed to Man Ray, as they were both artists supporting each other in doing what they loved.

Left: Lee Miller (American, 1907–1977). Untitled, 1930. Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.1 × 19 cm). © Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk. Right: Lee Miller (American, 1907–1977). Solarised Piano, ca. 1933. Gelatin silver print, 9 1⁄2 × 7 1⁄2 in. (24.2 × 19.1 cm). © Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

I don’t believe that Man Ray intended to take all of the credit for Miller’s rediscovery of solarization and for the work that she carried out for him, or her input on his projects: attribution was simply not necessary to either at the time, especially since they both ardently believed in the exchange of ideas and inspirations. There are also several examples of Man Ray promoting Miller’s career as a photographer. It was Man Ray who introduced the New York gallerist Julien Levy (1906–1981) to Miller’s work. Subsequently, Levy represented Miller and gave her first solo exhibition in New York, which opened on December 30, 1932.

Unfortunately for Miller, when it came to recording the histories of photography, she had several factors against her, mainly the relative lack of canonical recognition for female artists. Another possibility is that after World War II, when suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, she buried her photography career as a way of coping with her mental health issues. While these presented challenges for Miller, her relationship with Man Ray endured.

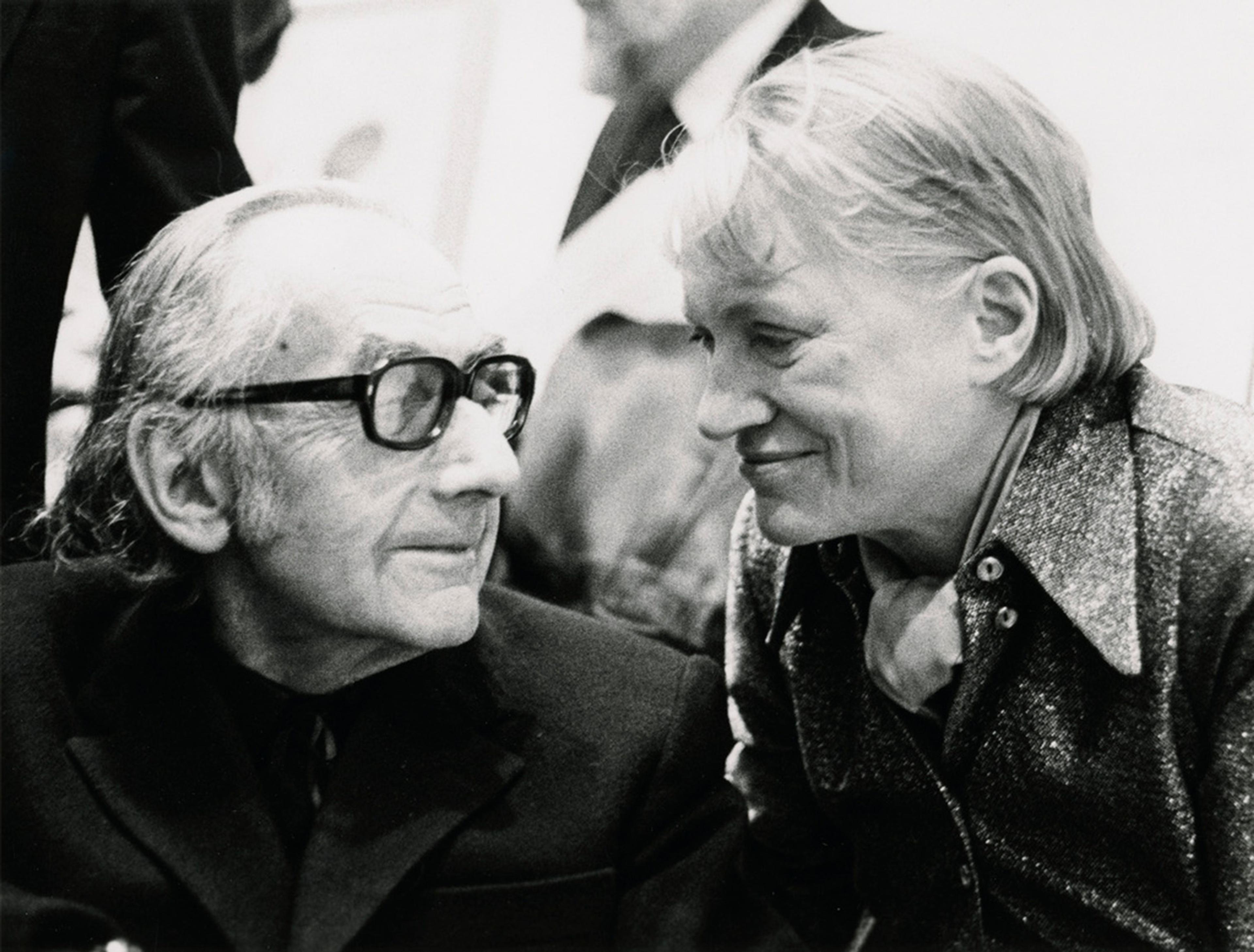

Photograph of Man Ray and Lee Miller from 1975. Taken by Eileen Tweedy. © Lee Miller Archives, England 2025. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk

Man Ray visited Miller at her East Sussex home multiple times between 1954 and 1966. She and her second husband, Roland Penrose (1900–1984), also visited Man Ray in Hollywood and Paris on several occasions, and there was sustained correspondence between them. Man Ray even appointed Miller to represent him at Les Rencontres d’Arles, a renowned photography festival, when he was honored there in 1976 but too unwell to attend. In what is believed to be the final letter Man Ray wrote to Lee Miller on March 14, 1975, he signed off: “I am pinned down in my little retreat—cannot walk and my doctor seems to try out all the pills on the market—to which I am completely allergic. But not to my loves—like you, I mean—I love you. Man.” The fact that Man Ray and Lee Miller remained in touch as friends until the end of their lives is testimony to the affection and respect they had for each other.

Notes

[1] Mario Amaya, “My Man Ray: interview with Lee Miller Penrose,” Art in America, May/June 1975, 55.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Parisienne de Distribution d’Électricité. See "Introduction" in D’Alessandro and Pinson, Man Ray: When Objects Dream (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2025), 29–30.