In his first-ever letter to Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), written on December 1, 1920, in response to a request for contributions to Dadaglobe, Man Ray noted: “I shall be glad to help you in any way, although I am very poor at collaboration when a movement involves more than two people.”[1] A collaboration of two people, like the one Man Ray actively enjoyed with Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) at the time, revolved around a circuit of making and receiving. The artwork needed to be seen in order to be completed. Man Ray’s works had to be seen by Duchamp; Duchamp’s works had to be seen by Man Ray, or by his surrogate, the camera.

This method of collaboration—to make and to be seen—is helpful in understanding the generative relationship that developed between Man Ray and Tristan Tzara, which began, I would argue, almost a year before their epistolary contact and in-person meeting with Tzara’s initial viewing of Man Ray’s photographs in reproduction. Their work together famously culminated in Man Ray’s “discovery” of the rayograph process in winter 1921, his film Le retour à la raison (1923), and Tzara’s two remarkable essays on the photographer of 1922 and 1934.[2] From the first instant, Tzara saw and understood. He completed the circuit. What he concretely offered was endorsement and promotion, but the spark, the generative force, was recognition: an understanding that Man Ray’s objectives—to mobilize photography to overturn not only the expectations of the medium but of artistic practice more broadly—aligned squarely with his own.

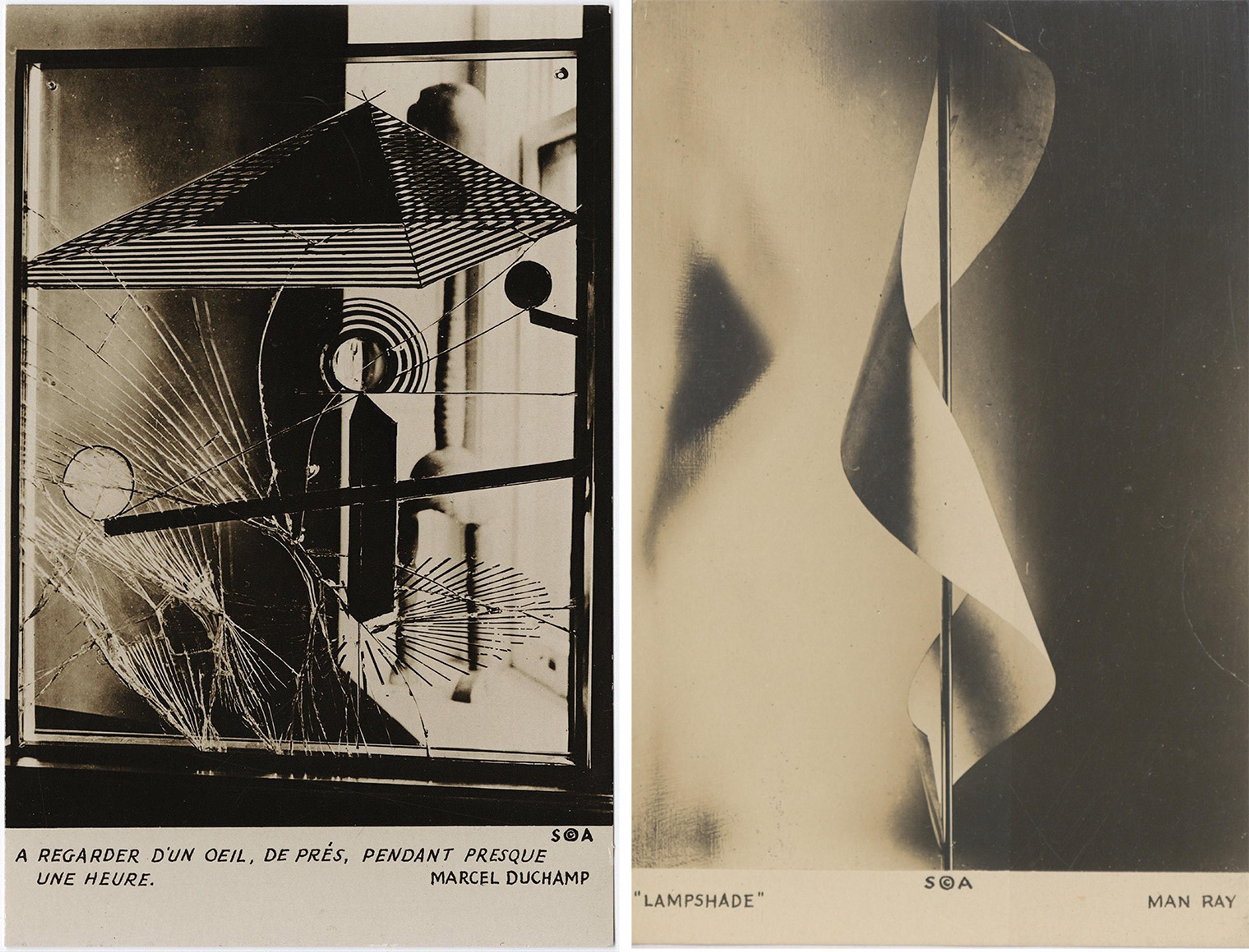

Postcards for the Société Anonyme published for their first exhibition in New York between April and June 1920 featuring À regarder d’un oeil, de près, pendant presque une heure (To be looked at with one eye, close to, for almost an hour), 1918 (left) and Lampshade, 1920 (right). Katherine S. Dreier Papers / Société Anonyme Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven

Two photographs by Man Ray appeared in the July 1920 issue of Francis Picabia’s (1879–1953) journal 391. One pictured Marcel Duchamp’s small glass object À regarder d’un oeil, de près, pendant presque une heure (To be looked at with one eye, close to, for almost an hour) (1918) and the other Man Ray’s own unfurled Lampshade (1920).[3] Neither image offered a clear, isolated view of the object. Rather, in each case, context was emphatically included: a sculpture by Brancusi, for example, was seen through Duchamp’s glass, and the shadows cast by Man Ray’s lampshade accompanied it at left. Incorporating such surrounding “static” created visual confusion. It also transformed the object and its surroundings into something new: a two-dimensional, photographic composition in black and white with its own formal, semiabstract properties.

Up until this point, in his capacity as editor of the journal Dada, Tzara had seemingly given little thought to photography beyond its service as a reproductive medium. The 391 photographs by Man Ray were defiant. They refused to function transparently, instead abstracting their subject matter and asserting their own presence. The same issue of 391 included what appears to be Tzara’s first published words on photography: “Mettez la plaque photographique du visage dans le bain acide. Les commotions qui l’ont sensibilisée deviendront visibles et vous suprendront.” (Put the photographic plate of the face in the acid bath. The disturbances that sensitized it will become visible and will astonish you.) For Tzara, the chemical process of developing the photograph enacted an automatic, almost magical transformation of the image, independent of the maker’s choice or control. The agency of the acid bath, as it were, upended artistic production, rendering the artist a passive observer. Filtered through Tzara’s Dada sensibility, the stakes of this reversal were high. They amounted to nothing less than the artist’s self-annihilation: “Foutez-vous vous-même un coup de poing dans la figure et tombez morts.” (Punch yourself in the face and drop dead.) The discourse surrounding photography, the machine, and automatization that had arisen in the circles of Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and Marcel Duchamp had been transmitted from New York via Picabia and received and registered by Tzara in Paris.

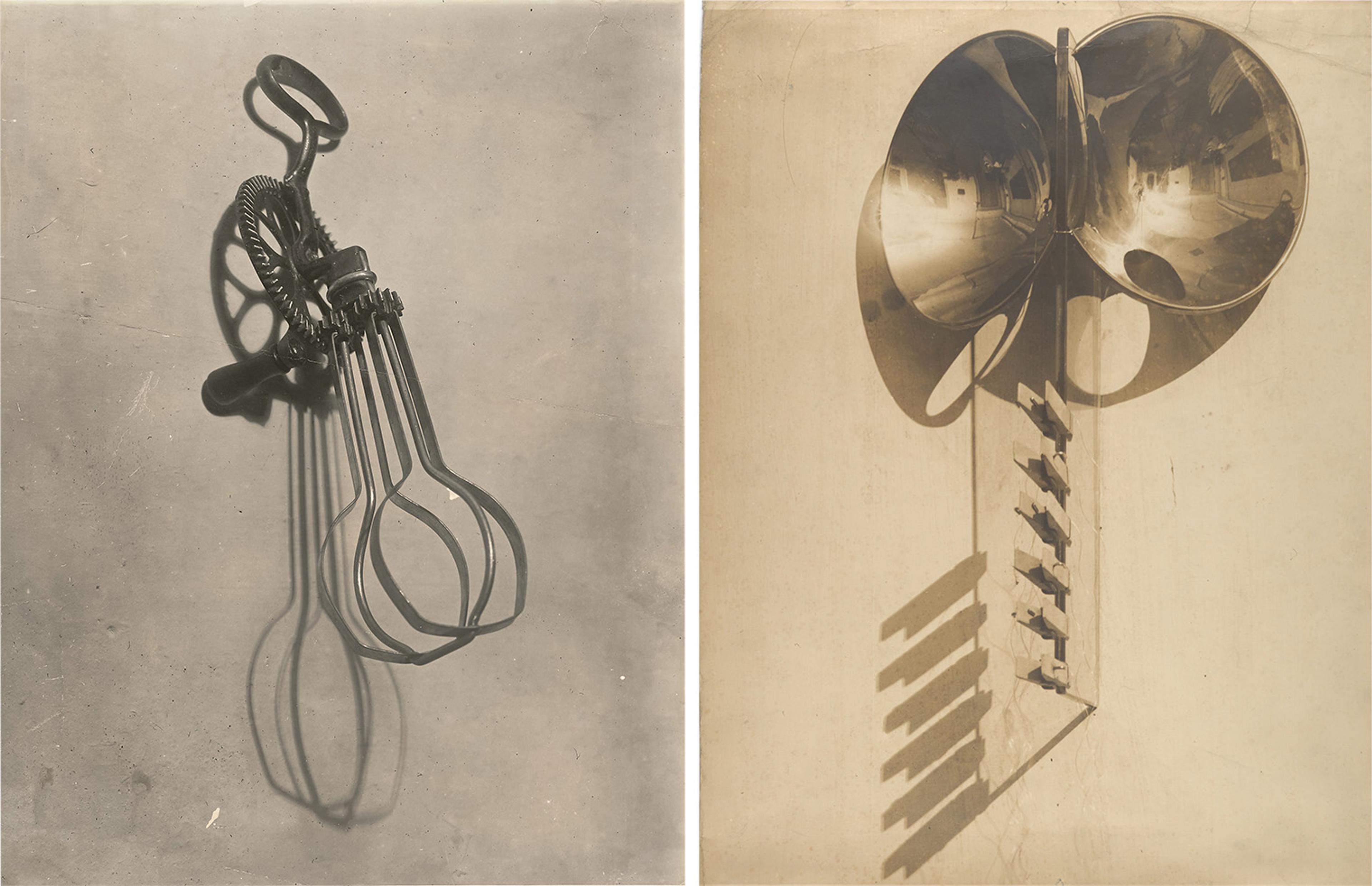

Left: Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). L’homme (Man), 1918–20. Gelatin silver print, 19 × 14 1/2 in. (48.3 × 36.8 cm). Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025. Right: Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). La femme (Woman), 1918–20. Gelatin silver print, 17 3/16 x 13 3/16 in. (43.7 x 33.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005 (2005.100.206). © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Energized and bolstered, Man Ray sent a carefully selected group of photographs to Tzara for Dadaglobe. Standouts among these were his L’homme (Man) (1918–20) and La femme (Woman) (1919–20), two large-scale photographic prints, whose titles and format thematized binary pairing—male and female, maker and receiver.[4] The photographs pictured assemblages of common objects, some of which were disassembled after the photograph was taken; as such, they inverted the primacy of the photographic trace over the object itself, elevating the photograph to the status of primary object. Reveling in such structural reversals, Tzara exhibited the pair at his Salon Dada in June 1921 and seems to have brought the prints with him to Tyrol later that summer, where he showed them to Jean Arp (1886–1966) and Max Ernst (1891–1976) who, respectively, requested duplicate copies and attempted to organize an exhibition of Man Ray’s photographs in Germany that fall.[5] In his premature announcement of that (seemingly unrealized) exhibition, Tzara highlighted Man Ray’s intention to renounce painting in favor of making “photographs, whose originals are destroyed.”[6]

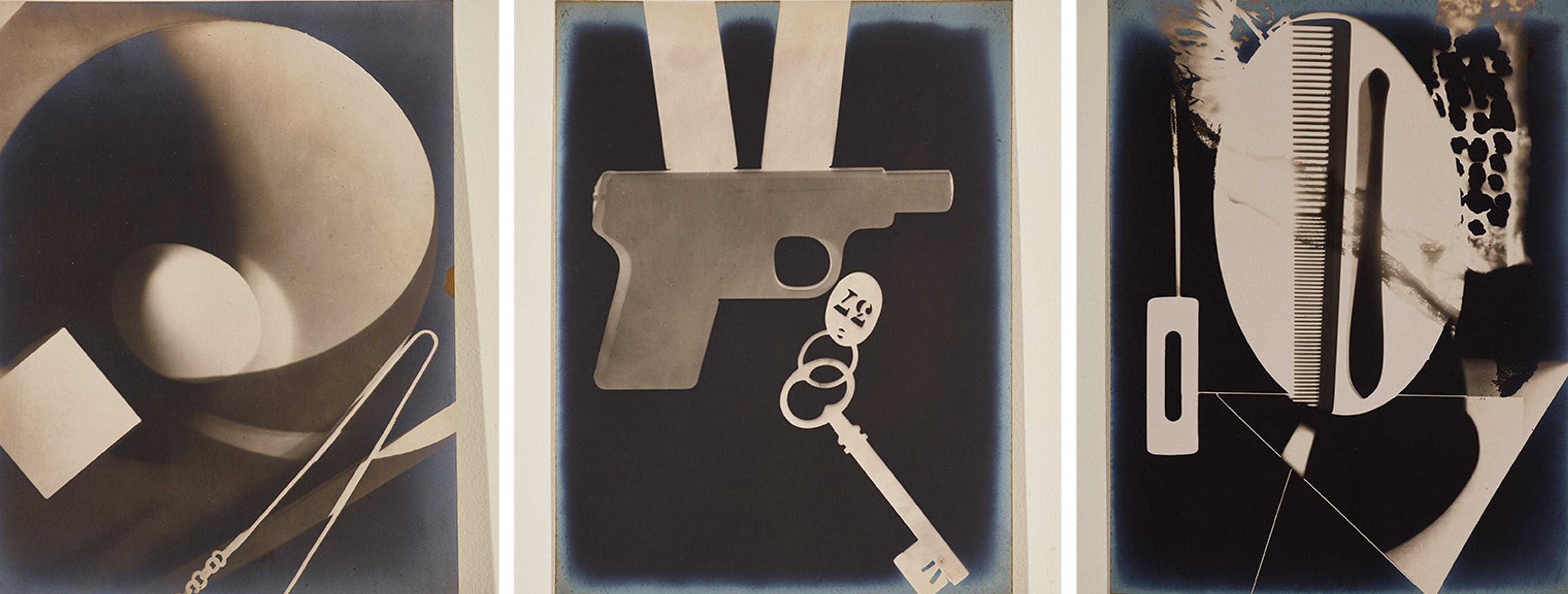

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Three photographs from the Champs délicieux (Delicious Fields) portfolio, 1922. Portfolio of twelve gelatin silver prints with cancellation marks, 15 3/4 × 11 13/16 × 13/16 in. (40 × 30 × 2 cm). Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

In early October 1921, Man Ray and Tzara finally met in Paris. The six months between their meeting and the announcement of Champs délicieux (Delicious Fields) in Tzara’s Le coeur à barbe in April 1922 is the stuff of legend: an undocumented and mysterious period in which Tzara may have shown Man Ray his stash of Christian Schad’s (1894–1982) unique photograms of 1919, prompting the revelation of the rayograph.[7] Tzara registered the idea of acknowledging the chance effects of the photographic “acid bath” in June 1920. Man Ray wrote about his desire to “make my photographs automatic” in a February 1921 letter to Katherine Dreier (1877–1952).[8] What occurred in between their meeting in October 1921 and the announcement of Champs Délicieux in April 1922 may have involved Schad’s photograms, but the generative circuit of making and receiving wasn’t completed until Tzara sent Man Ray his preface to Champs Délicieux on August 29, 1922, in which he declared a transformative occurrence in the history of art—the relinquishing of artistic control to anonymous, mechanical forces—that sent shock waves through the artistic practice and discourse of the day, and continues to resonate today:

When everything we call art had become thoroughly arthritic, a photographer lit up the thousand candles of his lamp, and the sensitized paper absorbed bit by bit the black outlines of some everyday objects. With a fresh and delicate flash of light, he invented a force that surpassed in importance all the constellations intended for our visual pleasure.[9]

Notes

[1] This letter is reproduced in Adrian Sudhalter, ed. Dadaglobe Reconstructed (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich and Scheidegger and Spiess, 2016), 76, fig. 14.

[2] In his notoriously unreliable 1963 memoir, Man Ray insisted on his sole discovery of the rayograph process, but credited Tzara with the idea of creating a film with rayographs, neither of which seems fully accurate. Man Ray, Self-Portrait (London: Penguin, 2012), 128–129, 260. See “Introduction,” in D’Alessandro and Pinson, Man Ray: When Objects Dream (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2025), 21–23.

[3] 391, no. 13 (July 1920): n.p. [2, 4]. Both images were published as postcards, as pictured above, on the occasion of the first Société Anonyme exhibition in New York from April to June 1920.

[4] For an extended discussion of the significance of pairing and its innate reversibility, see Sudhalter, Dadaglobe 2016, 51–52.

[5] To my knowledge, no evidence (such as reviews) has confirmed that an exhibition of Man Ray’s photographs took place in Germany in 1921 or 1922.

[6] Tristram Shandy (pseud. for Tristan Tzara), "Frankreich: Bulletins des Arts, Paris (en octobre 1921)," Ararat, vol. 2, no. 11 (November 1921), 279.

[7] For the most complete chronology of these events, see Clément Chéroux, “Les discours de l’origine: À propos du photogramme et du photomontage,” Études photographiques, no. 14 (January 2004): 34–61 and Clément Chéroux, “Tzara, fil rouge du photogramme à travers l’Europe,” in Tristan Tzara l’homme approximative (Strasbourg 2015), 243–57.

[8] Cited in Anne Umland and Adrian Sudhalter, eds. Dada in the Collection of The Museum of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 228, n. 10.

[9] Tristan Tzara, “Man Ray: La photographie à l’envers,” Champs Délicieux: album de photographies (Paris: Société générale d'imprimerie et d'édition, 1922), translated in Christopher Phillips, Photography in the Modern Era: European Documents and Critical Writings, 1913–1940 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Aperture, 1989), 4–6.