Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) and Man Ray enjoyed particularly fruitful collaborations in New York from January 1920 to June 1921, culminating in the first appearance of Duchamp’s female alter ego, Rose Sélavy, photographed by Man Ray, on the cover of the single issue of their magazine, New York Dada, in April 1921.[1] Paradoxically, this generative moment was also a period of uncertainty and change for both artists on personal and social levels. Many of the friends who had made New York such a vibrant vanguard center between 1915 and 1918 had left the city, and each had arrived at a turning point in his own work. Duchamp, having given up oil painting on canvas in 1918, was to leave his large glass La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [The Large Glass]) (1915–23) unfinished in New York after returning to Paris in 1921. This withdrawal from painting, and Man Ray’s new mastery of the camera, led to several unexpected and radical projects involving word games, optical effects, a moving machine, and photography.[2]

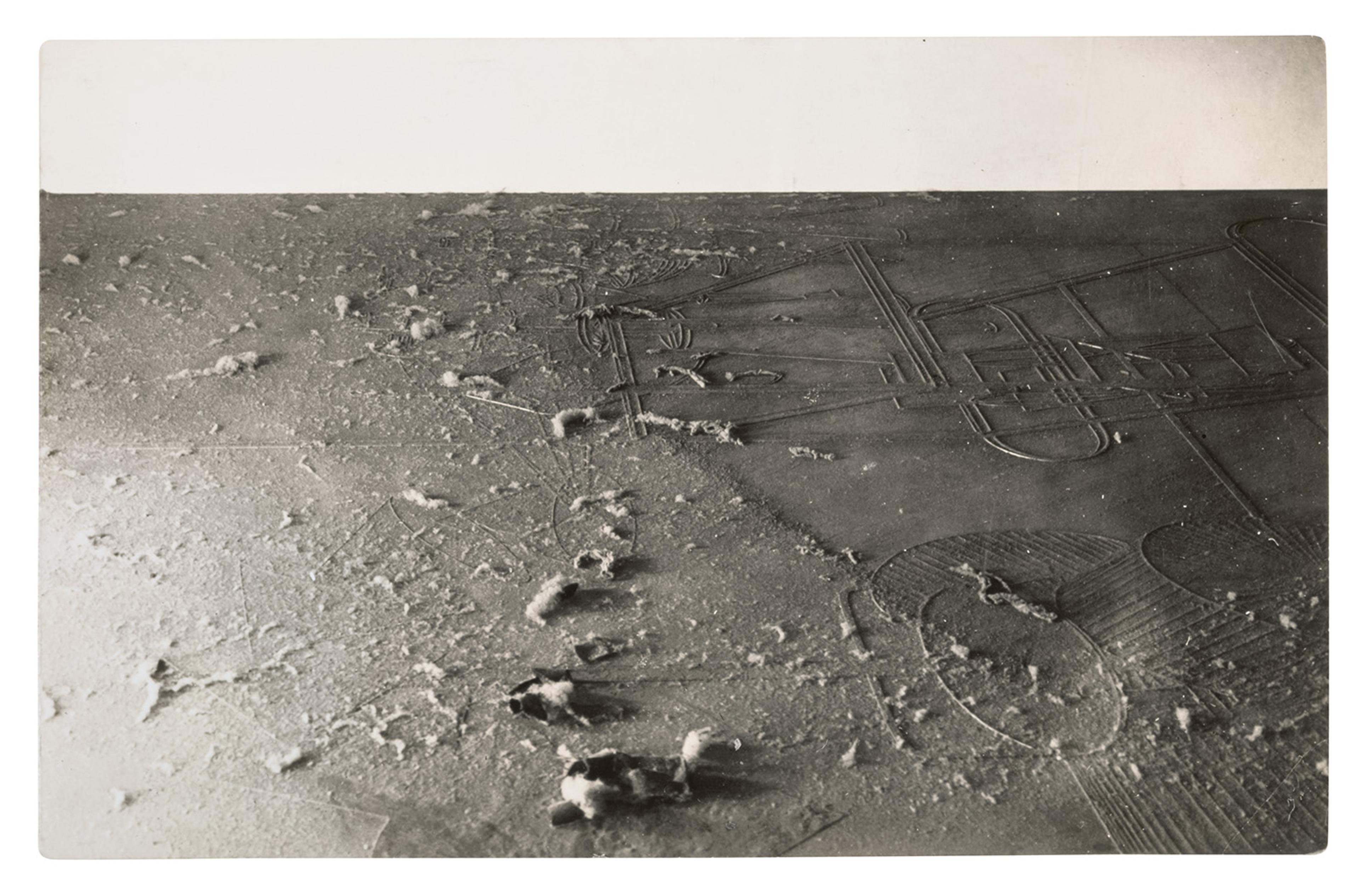

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Élevage de poussière (Dust Breeding), 1920. Gelatin silver print, 2 13/16 × 4 5/16 in. (7.1 × 11 cm). Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Watching Duchamp in his studio slowly scrape meticulous lines in the mirrored surface of his glass, Man Ray suggested that there might be a photographic process to speed things up. Duchamp agreed, suggesting that perhaps in the future photography would replace all art. Man Ray offered to bring his large plate-glass camera to Duchamp’s studio—the first time it had left his place. Man Ray infused a photograph with poetry, making it function metaphorically. When he fixed his camera on the tripod in Duchamp’s bleak studio and looked down on the dusty glass panes, he saw in them a “strange landscape from a bird’s eye view.” Framed to exaggerate this effect, Élevage de poussière (Dust Breeding) (1920) was reproduced in the special “Rrose Sélavy” issue of the Paris Dada magazine Littérature: “View taken from an aeroplane by Man Ray.”[3]

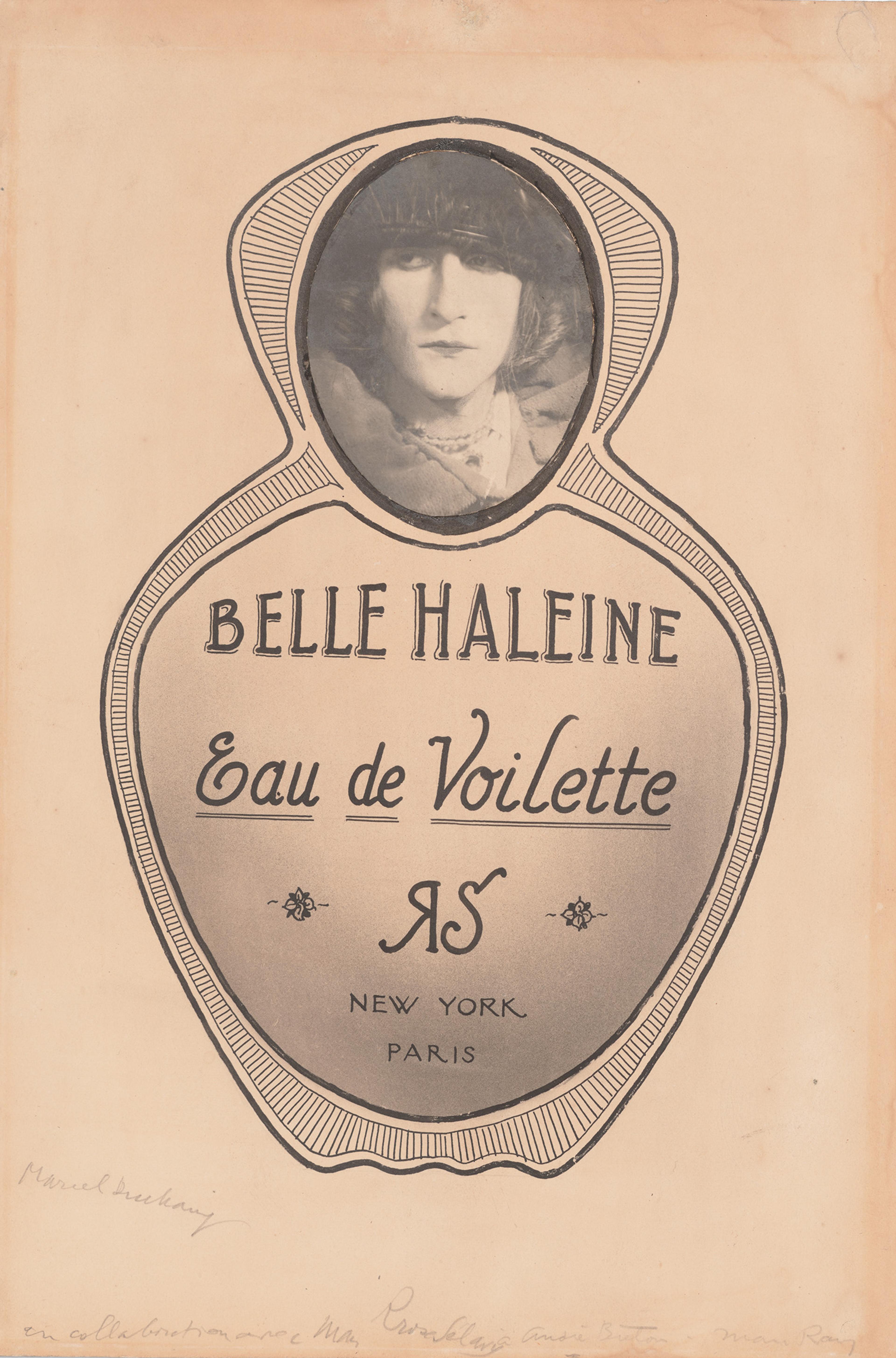

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Belle Haleine (Beautiful Breath), 1921. Gelatin silver print, 22.4 × 17.8 cm (8 13/16 × 7 in.). Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Both artists enacted masquerades for the camera. With Man Ray’s help, Duchamp created an alternative identity. At first, he thought of adopting a Jewish name, then had another idea: “Why not change sex? It’s much simpler! So that was the origin of the name of Rrose Sélavy.”[4] Rose Sélavy’s visual debut was on the cover of New York Dada in Man Ray’s initial series of photographs of Duchamp en femme (dressed as a woman). She looks austere, in contrast to Man Ray’s second series, shot in Paris later in 1921, in which she is markedly glamorous and feminine. At the center of the cover, a framed photograph of the assisted readymade Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette is surrounded by the words, upside down, “new york dada april 1921.” The assisted readymade, jointly produced, consisted of a Rigaud perfume bottle, whose label was replaced with a collage, an “imitated rectified readymade”: the photograph of Rose Sélavy above the new title Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette, or “Beautiful Breath: Veil Water” (suggesting mouthwash rather than perfume), alongside her initials in reverse.

While Duchamp designed the cover, Man Ray took over the layout: “I chose the contents at random—the first things that came to hand,”[5] which included his photographs of the artist Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874–1927), naked. Duchamp wrote to Picabia in Paris, asking him to get Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), the leading Dada entrepreneur, now in Paris, to send a short “authorization” to print, which Tzara did.[6] New York Dada was thus an assertion of their authority as affiliates of Paris Dada and an ironic response to Dada’s now-fashionable status, notably in the premier New York avant-garde magazine, The Little Review, which reprinted Dada manifestos and claimed: “Paris has had Dada for five years and we have had Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. Great minds think alike…”[7] For Man Ray and Duchamp, von Freytag-Loringhoven was the ultimate artist’s model. These collaborations between Man Ray and Duchamp during their lifelong friendship continued at many levels, often involving photography as well as their respective deployments of the readymade,[8] and embodied the exceptional nonconformist spirit they shared.

Notes

[1] She acquired the double “Rr” when Duchamp added his signature, along with Picabia’s other friends, to Picabia’s L’oeil cacodylate, in the autumn of 1921, thus producing a double pun: “Éros c’est la vie“ (Eros that’s life), and “arroser la vie” (water life), as well as “Rose, c’est la vie” (Rose, that’s life).

[2] Man Ray photographed Duchamp’s optical machine Rotary Glass Plates (1920), including a stereoscopic image. For more on this collaboration, see "The Tangible Object" in D’Alessandro and Pinson, Man Ray: When Objects Dream (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2025), 182–83.

[3] “The domain of Rrose Sélavy…” Littérature, new series, no. 5 (October 1, 1922).

[4] Pierre Cabanne, Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (Paris: Éditions Pierre Belfond, 1967), 118.

[5] Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (Thames & Hudson: London, 1997), 899.

[6] Marcel Duchamp, Affectionately, Marcel: The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk (Ghent: Ludion Press, 2000), 95.

[7] The Little Review 7, no. 2 (July–August 1920): 121. For more on the role of the Little Review at this time, see "Introduction" in D’Alessandro and Pinson, Man Ray: When Objects Dream (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2025), 27.

[8] Adin Kamien-Kazhdan, Remaking the Readymade: Duchamp, Man Ray and the Conundrum of the Replica (London: Routledge 2018).