Prestige Staff: Saint Anthony of Padua

Not on view

Uniting symbols of Kongo religious and secular power, this prestige staff was used as an insignia of office by a Kongo chief. At its summit is a brass pendant of St. Anthony of Padua, one of the most beloved saints in Kongo Christianity. The figure’s attributes confirm his identity: the cross held in his proper right hand, the Christ child balanced on his left hand, and his simple habit. The saint’s head is oversized in relation to his body, providing an expansive surface for both his simply molded and detailed incised facial features. The raised oval eyes have horizontal indentations at their centers, the nose is a softly raised triangle, and the lips raise at the corners into a smile. His thick eyebrows gently arch, with vertical lines to delineate each hair. Above, his head is bald except for a ring of hair. Known as a tonsure, this shaved hairstyle represented an act of religious humility. The detail of his triple-knotted belt shows not only the sculptor’s powers of observation, but also hold symbolic power as representations of the three vows of the Franciscan order (poverty, chastity, and obedience). The fabric of the habit flows in long folds from the belt, pushing forward subtly to indicate the figure’s underlying limbs. The Christ child is wide-eyed, looking forwards as he stretches out his arm across the chest of the elder saint, gesturing towards the solid crucifix. Like St. Anthony, his head too is oversized. The toes and fingers are articulated with simple parallel lines. A hanging loop is placed between the figure’s shoulders, directly on top of the inverted triangle of the cowl (hood) of his religious garment; this would have allowed the figure to have originally functioned as a pendant. St. Anthony stands feet shoulder width apart on a thick circular base; a large nail placed between his feet secures the pendant to the wooden shaft of the staff.

Like the Kongo crucifix, the figure of St. Anthony became associated with secular prestige in the nineteenth century. Investiture ceremonies emphasized the connection between royal power and iron well into the nineteenth century, when mvwala staffs came into favor among regional chiefs. The wood or ivory figurative finials of mvwala staffs incorporate iconography and poses that reference the lineage of the owner. In this unusual example, the staff features a Saint Anthony pendant as its finial, announcing its Christian authority along with its ancient invocation of Kongo power. The staff’s slender iron tip allows it to be planted into the earth, linking the owner to the realm of the ancestors. Two flattened orbs with incised longitudinal lines punctuate the length of the smooth, red-brown wooden shaft. These orbs are makolo, symbolic of key points within a leader’s reign. The incised lozenges—arranged as pairs, trios, and chain-like strands along the staff at the base of the figure’s feet—are not decorative, but allude to a network of ancestors who grant chiefly power. Examinations performed in 2001, 2002, and 2013 by Conservator Ellen Howe, Conservator Leslie Gat, Conservation Scientist Mark Wypyski, Conservation Scientist Adriana Rizzo, and Conservation Fellow Ainslie Harrison, suggest that the brass pendant finial was most likely cast around a core, and then later attached to a metal hilt, indicating both its method of creation and its multiple uses over time.

Catholic since the late fifteenth century, the Kongo Kingdom fostered devotion to many saints. St. Anthony was among the foremost, and was called Toni Malau ("Anthony of Good Fortune") for his purported powers of healing and good luck. The popularity of Saint Anthony in Kongo was part of an early modern phenomenon in which the saint was equally popular in Europe, South America, and Africa. Born in Lisbon, Portugal in 1195, the Franciscan brother Anthony was canonized just one year after his 1231 death in Padua, Italy. Claimed as a patron saint by both Portugal and Italy, religious missionaries from both regions spread his cult globally. Soon after their 1645 arrival in Kongo, Italian Capuchin fathers began to spread the cult of St. Anthony. While most early images of the saint were brought from Europe, some came to Africa via other sources. Most missionaries traveled indirectly to Africa via Brazil, where they sometimes purchased religious sculptures from Portuguese colonial workshops. In the Kongo kingdom, locally made figures of Saint Anthony based on European prototypes became common around the eighteenth century. The practice most likely related to the saint’s popularity in the kingdom, and was possibly tied to the short-lived Antonian movement, during which the Kongo noble woman Beatriz Kimpa Vita gained a significant political following after declaring herself the reincarnation of St. Anthony. While the Antonien movement was successfully put down in 1706, St. Anthony remained popular long after. Considered the "Saint of Good Fortune" or the "Saint of Prosperity," Toni Malau figures continued to be used prominently in Kongo as forms of protection from illness, the troubles of childbirth, or other problems. They also were adapted into symbols of Christian power, as in this staff.

Kristen Windmuller-Luna, 2016

Sylvan C. Coleman and Pam Coleman Memorial Fund Fellow in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Exhibition history

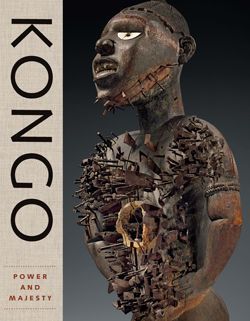

"Kongo: Power and Majesty," The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY: September 18, 2015–January 3, 2016

"African, Oceanic, and Ancient American Art: Recent Acquisitions," Michael C. Rockefeller Special Exhibition Gallery, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY: May 22–Oct. 28, 2001

References

LaGamma, Alisa.Kongo: Power and Majesty. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015, pp. 116–17, fig. 72.

LaGamma, A. 2001. "New Acquisitions: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York." African Arts. XXXIV (2):72–77.

Further reading

Fromont, Cécile. The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Pereira, Mario, and Kristen Windmuller-Luna. Kongo Christian Art: Cross-Cultural Interaction in the Atlantic World."

Kongo: Power and Majesty Exhibition Blog, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (blog), October 30, 2015.

Thornton, John K. The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.