Marmion Room

King George County, Virginia, ca. 1756

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner, Research Associate; and Moira Gallagher, Research Associate

This impressive seven-sided room, installed in Gallery 720, was the principal parlor of Marmion, a plantation house built around 1756 by the Fitzhugh family of Virginia. The room's elaborate painting was executed in the 1770s and is one of the most ambitious decorative schemes to survive from eighteenth-century America. In 1797, the house was purchased by George Washington Lewis, and his descendants continued to reside at Marmion until the late 1970s.

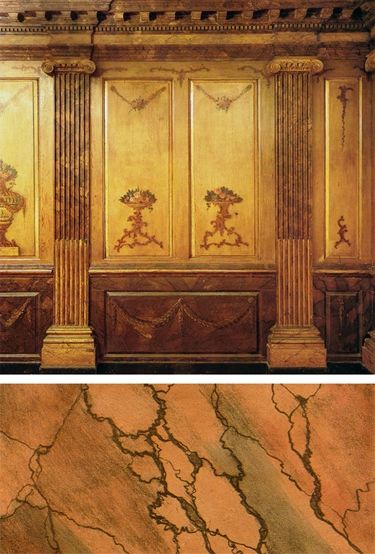

The Marmion Room has been left unfurnished so that visitors may study its hand-painted surfaces. The painting on the room's entablature, Ionic pilasters, and dado paneling imitates gold Siena marble, while Rococo-style ornaments embellish the paneled walls. Picturesque landscapes adorn a wall and the spaces above the fireplace and the door entrance.

An alternate view of the Marmion Room.

A tidewater plantation

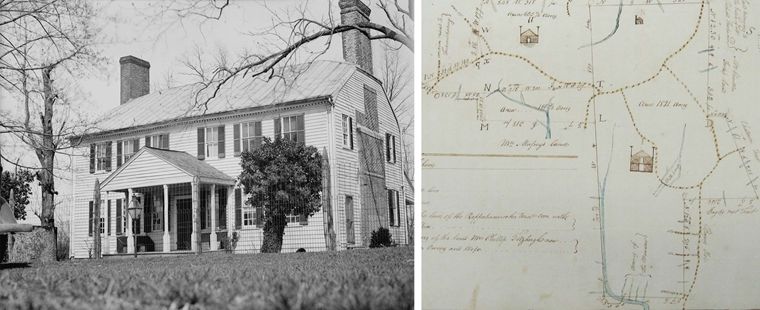

Left: Front facade of Marmion, ca. 1933. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS VA,50-COMO.V,2-. Right: This 1797 land survey includes a plan of Marmion and the neighboring house, Strawberry Hill. King George County Courthouse. King George, Virginia. Photo courtesy of Lee Dowdy

The Marmion plantation house was built around 1756 by William Fitzhugh (1725–1790) and his first wife, Ursula Beverley Fitzhugh (1729–1766/67). A large, seven-bay Georgian frame house of two stories, Marmion is similar in size and plan to other elite homes that were once scattered throughout the Tidewater region of Virginia.

The house has a jerkinhead roof, which combines a hipped and gabled roof. It is framed by brick chimneys, each of a different design with one featuring glazed headers, and clad in beaded white pine weatherboarding. A small porch shelters the front entrance and a larger portico extends across the rear of the dwelling. Four "dependencies" (smaller structures) surround the house: a dairy, a kitchen, a smokehouse, and an office. In 1789 William Fitzhugh described Marmion as a "plantation mansion, with houses, gardens, [and] orchards." The property also included various dwellings, which are no longer extant, to house the people and families who were enslaved there until 1865.

Location

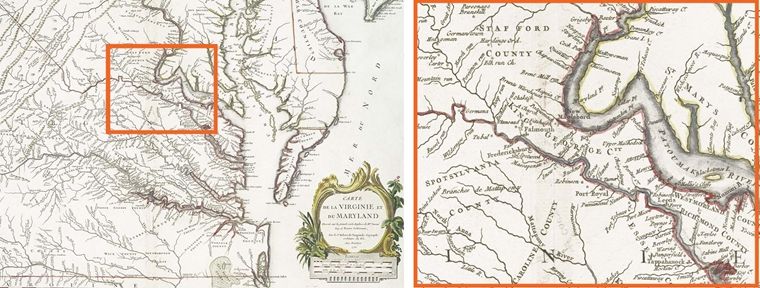

King George County, Virginia, as shown on a 1775 map by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson. New York Public Library

Marmion was built about three miles off-shore of the Potomac River in King George County, Virginia, on the ancestral homelands of Algonquian-speaking peoples, including the Nanzatico (Nantaughtacund), Patawomeck, and Rappahannock. King George County was established in 1720, and today it occupies a portion of the peninsula formed by the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. During the eighteenth century, its residents were primarily British settlers and their descendants, Indigenous peoples, indentured servants, and enslaved African Americans. Plantation owners and landholders in this region were among the wealthiest people in the North American colonies. Tobacco cultivation, land rents, and low labor costs due to enslavement and indenture yielded immense profits for these families, and positioned them as both suppliers and consumers in a robust network of trans-Atlantic trade.

Interior

The entry hall of the Marmion Hosue. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS VA,50-COMO.V,2-

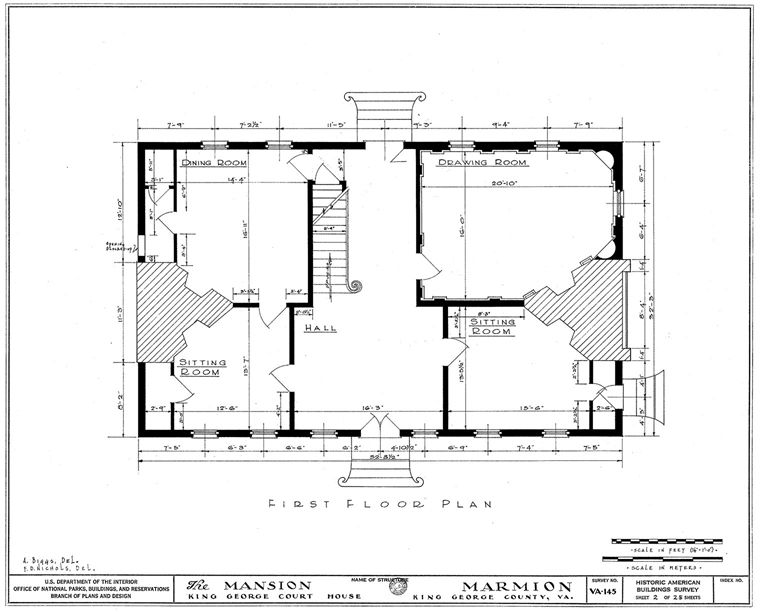

The simplicity of Marmion's exterior belies its interior, which features many-sided rooms and sophisticated paneling. The first story includes a central stair hall with two paneled rooms on either side. The larger, more ornate rooms were toward the rear of the house. The parlor on display in the Museum was located on the right side at the rear.

The central stair leads to a second-story landing hall that opens onto four or five bedrooms, three of which have fireplaces. The second-floor rooms exhibit simpler paneling, with plainer molding around the doors.

The first floor of the Marmion House. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS VA,50-COMO.V,2-

Life in the Parlor at Marmion

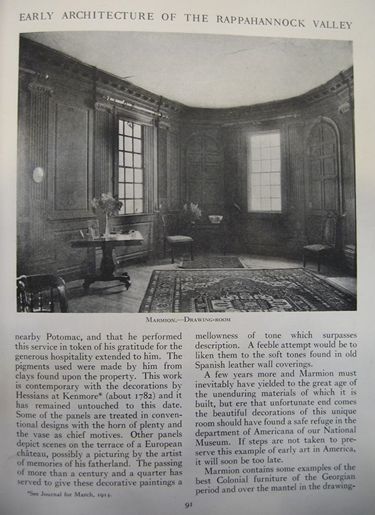

The parlor at Marmion was the largest and most elaborately decorated room in the house. As members of Virginia’s landowning elite, the Fitzhughs, and later the Lewis family, used this ornate chamber to entertain extended family, neighbors, and guests. While the room’s furnishings changed over time to reflect each owner’s personal tastes, the carved and gilded English Rococo overmantel mirror was likely installed soon after the house was built and remained with the room when it was acquired by the Museum. Various forms of seating furniture, tables, floor coverings, window draperies, and other imported and domestically produced furnishings and decorative items once completed the space. Today, the room is shown unfurnished at the Museum in order to draw attention to the decorative paint scheme.

Image: The Parlor from a 1916 article about the Marmion House in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects.

To maintain their elegant home, the Fitzhugh and Lewis families both relied on the labor of enslaved men and women. Within the main house, these individuals managed the household, cleaned, tended children, prepared meals, and served the families and their guests. During the early years of the nineteenth century, an enslaved man named Billy, who labored as a butler and manservant to George Washington Lewis, would have likely greeted the Lewis family’s guests and escorted select individuals to the parlor for visiting. Research conducted by curators at Historic Kenmore, Lewis’s childhood home, uncovered that Billy was enslaved by various members of the Lewis family for his entire life. (See Historic Kenmore for more on Billy).

![A notice issued by Daingerfield Lewis regarding John Stuart. [Notice], Alexandria Gazette [Alexandria, VA], April 7, 1835.](/-/media/images/about-the-met/collection-areas/american-wing/period-rooms/marmion-room/people/john-marmion.png?la=en&h=620&w=375&sc_lang=en&hash=F602B4AEC46FF579CEEF931A516A8823)

IIn 1835, Daingerfield Lewis, son of George Washington Lewis, ran a notice in the Alexandria Gazette, offering a $100 dollar reward for "my House Servant, JOHN," who identified himself as John Stuart or John G. Stuart. John may have been the Lewis family’s butler after Billy. About twenty-four years old and, five feet, nine inches tall, John was described as "a bright mulatto," who was literate and had medical knowledge. He left Marmion wearing “a blue domestic coat and pantalooms [sic]” and “took with him a close bodied green cloth coat” and other clothes, so he could “disguise himself by clothing or other means.” Other details provided in the notice point to the difficult life John endured. In addition to an injured left knee, Lewis noted a scar on his throat, supposedly "the effect of a pretended attempt to commit suicide." Lewis believed that John would “endeavor to escape to a Northern State”, as he had attempted previously. While research into John’s life is ongoing, documentary evidence suggests that his attempt to escape to freedom was unsuccessful as a “John Stuart” is listed among those enslaved at Marmion in Daingerfield Lewis’s 1862 probate inventory.

Image: A notice issued by Daingerfield Lewis regarding John Stuart in the Alexandria Gazette, April 7, 1835.

Architectural harmony

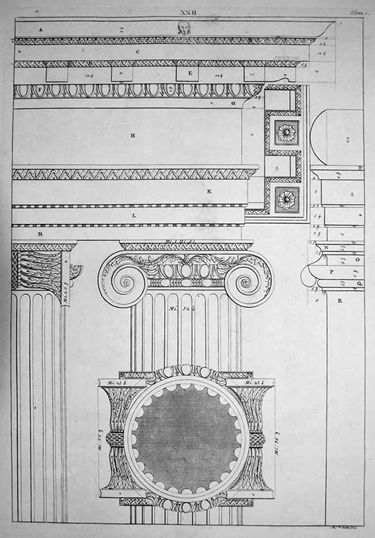

Left: Detail of one of the thirteen fluted Ionic pilasters in the Marmion Room. Right: This detail of plate 31 from volume 2 of the 1784 edition of Francesco Piranesi’s Le Antichità Romane depicts the ruins of the tome of Alexander Severus, including an Ionic capital with a foliate design that likely inspired Palladio’s original design over 200 years earlier.

Marmion's fully paneled parlor features a corner fireplace and two roundheaded cupboards. Thirteen identical fluted Ionic pilasters frame the doors, windows, chimneypiece, and panels to create visual symmetry in the asymmetrical space. The fireplace mantel is faced with gold Siena marble and a molding of white marble. An impressive entablature with modillions and dentils gives the room a bold sense of height and complexity.

Calder Loth, Senior Architectural historian (retired) at the Virginia Departments of Historic Resources, identified the design of the pilasters’ Ionic capitals as being sourced from Book 1, plate 22 of the 1721 Giacomo Leoni English language edition of Andrea Palladio's Four Books of Architecture, the most popular treatise on classical architecture originally published in 1570. The design, distinguished by branches of foliage in the capitals’ Ionic scrolls, may have been inspired by architectural elements associated with the tomb of Roman Emperor Alexander Severus.

Right: Plate 22 in book 1 of Giacomo Leoni’s English language edition of Andrea Palladio's Four Books of Architecture (1721),illustrates the plan of an Ionic capital similar to those on the pilasters of the Marmion Room.

Rococo trophies and picturesque landscapes

The Marmion Room boasts some of the most extravagant wall painting found in any surviving colonial American home. Decorative painting was popular with eighteenth-century homeowners, in part because it was less costly than hand-painted wallpapers, ornate architectural carvings, plaster moldings, and other such options for beautifying an interior. Here, the unknown artist made use of popular French Rococo ornament within the room’s classically inspired paneling. Four wall panels feature floral garlands and Rococo trophies, including an undulating flower-filled cornucopia, a classical urn, and two asymmetrical flower stands containing fruit and flowering vines. Above the mantel is a harbor scene, distinguished by a craggy arch topped by a windmill with a classical building in the foreground. The scene is flanked by two busts and a profusion of C- and S-scrolls accent the room. A picturesque scene of a thundering seascape ornaments the small panel above the room’s mahogany door, and two larger scenes—a streetscape and landscape with structure on a cliff complete the room’s decorative program. The artist likely copied such scenes from prints and book illustrations selected by the patron or from those the artist carried in their portfolio. Research is ongoing, but to date, specific print sources have not been identified for any of the scenes in the Marmion Room.

Paint analysis suggests that the eye-catching decoration was a part of a second decorative scheme, occurring sometime after the room’s initial construction, though its precise date of execution remains unclear. Amidst the profusion of Rococo motifs, one urn conveys a Neoclassical sensibility, leading curators and scholars to attribute the date of the decorative painting to the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

Top: The picturesque landscape on the overmantel of the Marmion Room features a windmill perched on an arched rock formation.

Bottom: This symmetrical urn in the Marmion Room suggests that the painted decoration may date to the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

The painter

Unfortunately, the wall painting is not signed and the identity of the artist responsible for this unique ornamentation remains unknown. Based on the attributed date, it is possible that the work was executed at the behest of William Fitzhugh, who owned Marmion until his death in 1791. The extended Fitzhugh family were some of the most active artistic patrons in colonial Virginia and they commissioned a large body of portraiture from artist John Hesselius, much of which is extant. William’s grandfather, the first of the family to settle in Virginia, acknowledged the significance of a strong cultural education and possessed works of art and an extensive collection of silver plate. William would have been keenly aware of the social clout one gained from domestic displays of art and may have commissioned an itinerant or regional artist to execute this ambitious program. For example, Charles Tinsley advertised the skills of an indentured servant he had recently engaged in the Virginia Gazette in 1773. He described the man as, “a good limner, landscape painter, &c. and an excellent hand at painting signs of all sorts... and can paint any kind of pictures as well, and as much to the life, as those imported from England.” An artist of similar ability could have undertaken the commission.

Unfortunately, the wall painting is not signed and the identity of the artist responsible for this unique ornamentation remains unknown. Based on the attributed date, it is possible that the work was executed at the behest of William Fitzhugh, who owned Marmion until his death in 1791. The extended Fitzhugh family were some of the most active artistic patrons in colonial Virginia and they commissioned a large body of portraiture from artist John Hesselius, much of which is extant. William’s grandfather, the first of the family to settle in Virginia, acknowledged the significance of a strong cultural education and possessed works of art and an extensive collection of silver plate. William would have been keenly aware of the social clout one gained from domestic displays of art and may have commissioned an itinerant or regional artist to execute this ambitious program. For example, Charles Tinsley advertised the skills of an indentured servant he had recently engaged in the Virginia Gazette in 1773. He described the man as, “a good limner, landscape painter, &c. and an excellent hand at painting signs of all sorts... and can paint any kind of pictures as well, and as much to the life, as those imported from England.” An artist of similar ability could have undertaken the commission.

Alternatively, there is a possibility that the painting was executed after 1797 during the Lewis family’s ownership of Marmion. When The Met acquired the room in 1916, Lewis family oral tradition attributed the room’s decoration to an unknown Hessian soldier, who was rescued by the family from the shores of the Potomac River during the American Revolution (1775–83) and painted the parlor in gratitude for the care he received. At first review, the story is easy to dismiss since the Lewis family did not come to own the property until over a decade after the Revolutionary War ended and the tale of a “talented Hessian solider” became an oft repeated legend during the Colonial Revival period. However, research has traced this story to an 1860 Virginia newspaper article where the author tells of his visit to Marmion writing, “The paneled sides of the antique drawing-room were painted by a Hessian soldier, who called to see Major George Lewis (father of Dangerfield [sic] Lewis) after the war.” Daingerfield, the owner of Marmion when the article was written, was a young teen when his father acquired the plantation in 1797 and likely held a reliable memory of the parlor receiving its decoration. If the decoration was commissioned by George Lewis, it is possible that the artist was German, leading his son to recall him as a Hessian soldier.

Image: A detail of the painting in the Marmion Room

The art of the decorative painter

To execute common motifs such as the urns, flower stands, and cornucopias seen in the Marmion Room, the decorative painter relied on cartoons, or line drawings, as templates. First, he traced a motif onto the wood panel to create an outline. He then used thin paintbrushes to fill in the image, applying one color at a time. Once the paint had dried, he applied an overlay of darker shades and touches of white to add shadows and details, giving the work dimensionality. When the work was completely dry, the artist added two coats of varnish for protection.

Top: A painted cornucopia in the Marmion Room overflows with flowers, fruit, and garlands of leaves.

Bottom: This detail on the painted urn in the Marmion Room features a delicately rendered scene of a small house within a grove of trees.

Marbling

The entablature, fluted Ionic pilasters, and dado paneling of the Marmion Room were painted to resemble architectural marbles, in particular the real gold Siena marble of the fireplace surround. The step-by-step process of imitating marbles in paint, called 'marbling,' is recorded in eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century decorative painting journals.

For the imitation gold Siena marble of the pilasters, the decorative painter laid down a base coat of pure yellow ocher, followed by a darker coat of burnt siena. While the base coat was still wet, the artist added dark wavy lines to imitate the veining in marble. One decorative journal advised that veins should be "drawn with great care and spirit ... by forming a small mass, and then branch[ing] off in different directions."

Top: The decorative painting in the Marmion Room is meant to imitate veined marble.

Bottom: Small sections of a panel were marbled at a time and then blended with a dusting brush to soften the overall appearance. Plate 18 in the decorative painter Nathaniel Whittock's The Decorative Painters' and Glaziers' Guide (1827)

The Fitzhughs

The Marmion planation house was built around 1756 by William Fitzhugh (1725–1790) and his first wife, Ursula Beverly (1729–1766/7). William was a third-generation Virginian and the extended Fitzhugh family had large land holdings in Virginia, along the Potomac River. Ursula was the daughter of William Beverley (1696–1756), who owned a successful tobacco plantation in Essex County and extensive lands in the Blue Ridge Mountains. As part of colonial Virginia's land-owning elite, William and Ursula Fitzhugh were well-connected and actively participated in a trans-Atlantic network of trade and consumption.

Upon William's death, ownership and management of the estate passed to his eldest surviving son Philip Fitzhugh; William's widow—his second wife, Hannah—was allowed to continue living at Marmion. Ongoing financial struggles likely prompted Philip to sell the plantation and other adjacent tracts of land in the final years of the eighteenth century. Advertisements for Marmion's sale appeared in local newspapers as early as 1793, and boast of well-timbered acres, a grain crop, pasture, orchards, "an excellent two story Dwelling-House," as well as stables and barns. In 1797, Marmion was sold out of the Fitzhugh family and purchased by George Washington Lewis.

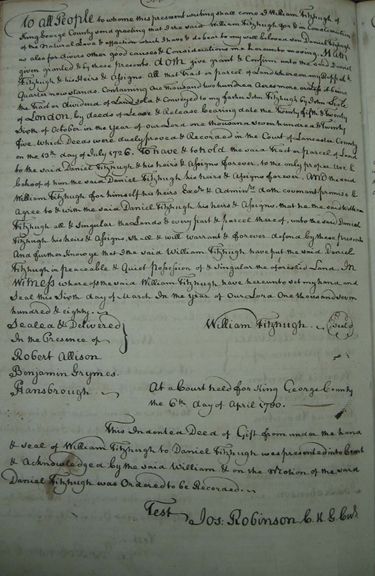

Image: William Fitzhugh's will dated April 6, 1780. In this document, he leaves Marmion to his heirs. King George County Courthouse, King George, Virginia. Photograph courtesy of Lee Dowdy

The Lewis family

The Lewis family in front of Marmion House, ca. 1907. Photograph courtesy of Barbara B. Powell

George Washington Lewis (1757–1821) and Catherine Daingerfield Lewis (1764–1820) purchased Marmion in 1797. George Lewis was the son of Fielding Lewis and Betty Washington, George Washington's younger sister, making him the nephew of the nation's first president. During the American Revolution (1775–83), George Lewis served as commander of his uncle's life guard and was noted to be a favorite relative. Newspaper advertisements suggest that Lewis intended to sell the plantation in 1820, but after his death in 1821 it came to be owned by his second eldest son, Daingerfield Lewis (1795–1862). It then passed to Daingerfield's son, Fielding Lewis (1808–1878), his widow and second wife Imogen Lewis (about 1831–1913), and then their daughter, Lucy B. Lewis, later Grymes (1874–1963), who sold the parlor to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1916. After being occupied by many generations of the Lewis family, the house was sold out of the family in 1977 and remains privately owned.

Slavery at Marmion during Fitzhugh ownership

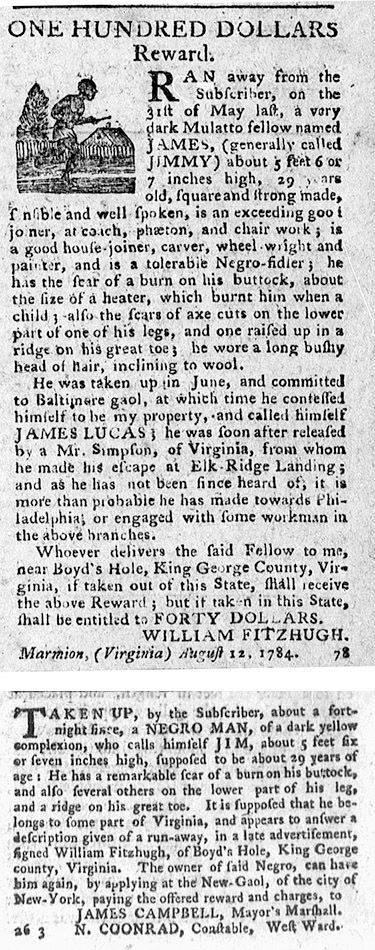

From its beginnings until the Civil War, Marmion operated as an agricultural plantation supported by the involuntary and unpaid labor of enslaved men, women, and children. Though it is not known how many people William Fitzhugh held in bondage, he enumerated at least twenty unnamed enslaved people in his 1789 will, all of whom he intended to bequeath to his surviving wife and children. Newspaper notices identify five men—Moses, James "Jemmy" Lucas, Tom, Jerry, and one unnamed man—who escaped their enslavement under the Fitzhugh family. To ensure recapture, such notices provided almost-clinical descriptions of the person's physical appearance, clothing, speech patterns, and/or skills. While these written portraits reflect the enslaver's point of view, they also recognize each person's individuality, which stands in stark contrast to the slavery's dehumanizing categorization of people as anonymous property. For example, the notices issued for the return of James Lucas, pictured here, identify him a craftsman who was highly skilled in various trades. Lucas likely used these skills to obtain work, finance his freedom, and evade recapture. Unfortunately, these same talents also made Lucas incredibly valuable to William Fitzhugh, who tirelessly pursued him for five months, from Virginia to New York, where Lucas was eventually recaptured.

Philip Fitzhugh's decision to sell Marmion also threatened the community and families he enslaved. A 1796 auction notice reported that "About fifty Virginia born slaves, a great proportion being prime young fellows, several carpenters, and one blacksmith," were to be sold at the plantation. Combined with William's will, the notice suggests that the family may have enslaved between fifty and seventy people, including a number of highly skilled craftsmen, during their ownership of Marmion.

Top: A notice issued by William Fitzhugh regarding James Lucas in the Independent Journal (New York), August 28, 1784.

Bottom: A notice regarding James Lucas' capture in the New York Packet, October 14, 1784.

Slavery at Marmion during Lewis ownership

It remains unclear how many, if any, of the people enslaved by the Fitzhughs were bought by George Lewis when he acquired the plantation in 1797. Just one year later, Lewis purchased at least nine enslaved people—George, Tom, Charles, Billy, Ned, Nanny, James, Randolph, and Joe—from his parents' estate at Kenmore and brought them to Marmion. By 1820, Lewis held over twenty people in bondage at the homestead.

His son, Daingerfield Lewis, was already established as a landholder and enslaver with a growing family of seven children when he assumed ownership of Marmion in 1821. According to the 1860 US Federal Census, Daingerfield and his three adult sons—Fielding (who would inherit Marmion two years later), George, and Henry Byrd Lewis—collectively enslaved over 140 men, women, and children ranging in age from sixty years old to under one at Marmion and on their nearby farms.

The onset of the Civil War in 1861 threatened the Lewis family's continued reliance on enslaved labor. Many members of the extended Lewis family fought for the Confederacy. However, Marmion's proximity to the Potomac River and the frequent presence of Union troops in the area proved opportune for enslaved people seeking freedom. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, a newspaper reported that forty people in King George County, including five people from Marmion, fled enslavement to the Union lines. The article noted that as of November 1861, at least one hundred people, estimated to be worth $100,000, had taken similar action to achieve their freedom. With the cessation of the war and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, chattel slavery ceased to be legal.

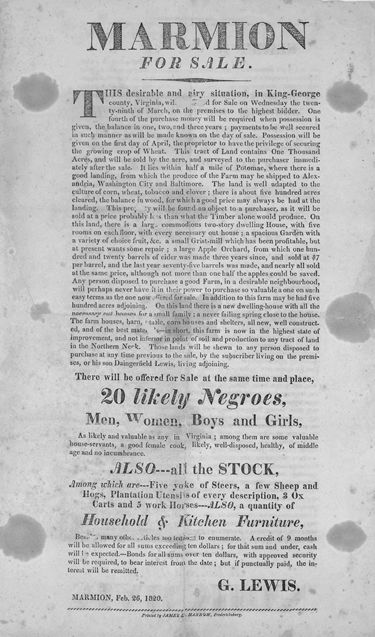

Image: A broadside advertising the sale of Marmion, dated February 26, 1820. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Printed Ephemera Collection

Life after the Civil War

The overthrow of Reconstruction—the postwar period of unification that brought major gains for the recently emancipated—saw the reversal of much of that progress in civil rights. Reports issued by the county's representative from the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands document that racial tensions ran high, and that unfair rents, voter suppression, and threats of eviction and violence were widespread. With the withdrawal of federal troops from the South, ongoing systemic discrimination and segregation of Black people in Virginia led some individuals to move North in search of greater opportunities.

Despite the ongoing challenges, many people remained in King George County and continued to enrich the region's longstanding Black community. According to the 1870 Census, the families of Thomas Jackson and Thomas Brown lived on properties adjacent to Marmion. Brown, a blacksmith, may be the formerly enslaved "Tom Brown," who appears in Lewis family papers, or his direct relation. Jackson, a carriage driver, was married to Nancy, who is likely the Nancy Jackson recorded as giving birth in 1854, while enslaved by Daingerfield Lewis. The census lists the Browns' son, Abram, as being sixteen years old. While the dates of his parents' deaths are currently unknown, Abram Jackson continued to live on a farm he owned in King George County until his death in 1921. He and his wife, Virginia, raised their daughter, Bertie, and granddaughter, Minnie, there and were members of the Pilgrim Church of the Living God.

Acquisition of the Marmion Room

The Marmion plantation house descended in the Lewis family largely unchanged through the nineteenth century. When Lucy Brockenbrough Lewis (1874–1963) came into possession of the home in 1915, she decided to sell the parlor. To promote the sale, she hired the architectural historian Frank Conger Baldwin.

In the March 1916 issue of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects, Baldwin published the first-ever article on the house. Three months later, the Metropolitan Museum acquired the Marmion Room, with Baldwin acting as the broker. Curators initially discussed removing the painted decoration and "recoloring" the room for installation purposes. Thankfully, no action was taken, and the painting is now regarded as the room's most significant feature.

Image: Frank Conger Baldwin's article about the Marmion House in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects (March 1916)

Moving the Marmion Room

The Marmion Room in 1924, as shown in The Homes of Our Ancestors (1925) by R. T. H. Halsey and Elizabeth Tower

The Marmion Room was one of the original period rooms installed in the American Wing when it opened in 1924. At that time, it was furnished with Philadelphia Rococo-style furniture, because the Museum did not have any Virginia furniture in its collection.

During the expansion of the American Wing in 1980, the room was moved to a new gallery beyond the original American Wing. The room was left unfurnished in order to highlight its architecture and painted decoration. During the 2008 renovation, the Marmion Room was moved back into the original American Wing. The looking glass was restored and a doorway was added in place of a window so that visitors can walk through the room to experience the space and examine the painted walls more closely.

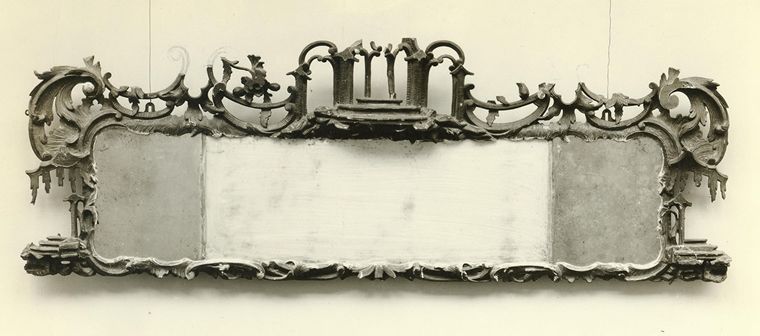

Looking glass

Looking glass above the fireplace in the Marmion Room before restoration. Courtesy of Preservation Magazine. 1991 Looking glass, 1750–75. Made in England. Pine, gilded plaster. 23 x 66 in. (58.4 x 167.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1928 (28.49)

Looking glasses were a stylish and expensive luxury in eighteenth-century America. Mirror glass was almost always imported, as were the carved wood frames. Because of the cost and fragility of mirror glass, large looking glasses, like this one, were made from three separate plates of glass, placed flush against one another to give the illusion of a continuous plate.

Pairs of sconces and other lighting devices often flanked looking glasses in order to reflect light throughout a room. The Marmion looking glass originally had double sconces at its lower corners. The light from the fireplace and the candles would have flickered and danced across the carved-and-gilded surface, creating a dazzling display of light and shadow.

Made in England, the Rococo carved-and-gilded overmantel looking glass of the Marmion Room was probably installed when the room was painted in the 1770s. The frame features pierced scrollwork, C-scrolls of acanthus leaves, shellwork, and a central Chinese pavilion considered "exotic" by eighteenth-century standards. The looking glass was likely custom ordered to fit the space above the fireplace, where it was screwed into the wall and considered a permanent architectural fixture.

Design sources

Plate 34 in Thomas Johnson's New Book of Ornaments (1762)

The carved ornament on the frame of the looking glass is reminiscent of designs found in well-known European pattern books, but a direct source has not been determined. The combination of C-scrolls, foliage, and shellwork is in keeping with the Rococo aesthetic fashionable in America during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. The asymmetrical carving also parallels the painted fruit stands on the paneling to the right of the fireplace.

Conservation of the looking glass

The Marmion Room's looking glass before conservation

Marmion's overmantel looking glass was in poor condition when it came to the Museum in 1916. Years of heat from the fireplace, dusting, cleaning, and the passage of time had taken a toll on the fretwork. When the room opened to the public in 1924, the looking glass was displayed in its damaged state. Several years later, the looking glass was restored, with all the replaced elements left ungilded. In 2008, the looking glass was examined once more. Some elements from the original restoration were altered in the interest of even greater historical accuracy, and new gilding was applied so that the new carving would blend with the old.

The art of conservation

When the Museum acquired the Marmion Room in 1916, curators analyzed the "ghost" of an outline of the overmantel looking glass visible on the paneling above the fireplace. The outline suggested that the looking glass was installed at the same time the room was painted, meaning that it is most likely original to the room.

When the Museum acquired the Marmion Room in 1916, curators analyzed the "ghost" of an outline of the overmantel looking glass visible on the paneling above the fireplace. The outline suggested that the looking glass was installed at the same time the room was painted, meaning that it is most likely original to the room.

Continued investigation into period documentation relating to Marmion's residents, architectural research, and scientific testing have provided curators and conservators with new insights into the room’s use and history.

Image: "Ghost" outline of the Marmion looking glass. Photograph courtesy of Lee Dowdy

Tree-ring dating

New technologies have shed light on the Marmion Room. To discover Marmion's date of construction, tree-ring dating method, or dendrochronology was done at the original house, which remains standing. The process involved removing a small core sample of wood from timbers of the house and analyzing their ring patterns. The initial test of Marmion yielded a construction date of 1754, and a second test produced a slightly later date, 1758. Period documentation supports the scientific analysis: Ursula Fitzhugh's father died in 1756, leaving her a large bequest in his will, and the spike in the couple's finances would have enabled them to build Marmion. As a result, a construction date of around 1756 has been assigned to the house.

New technologies have shed light on the Marmion Room. To discover Marmion's date of construction, tree-ring dating method, or dendrochronology was done at the original house, which remains standing. The process involved removing a small core sample of wood from timbers of the house and analyzing their ring patterns. The initial test of Marmion yielded a construction date of 1754, and a second test produced a slightly later date, 1758. Period documentation supports the scientific analysis: Ursula Fitzhugh's father died in 1756, leaving her a large bequest in his will, and the spike in the couple's finances would have enabled them to build Marmion. As a result, a construction date of around 1756 has been assigned to the house.

Image: Every year, a tree adds a layer of wood underneath its bark. Examination of these annual growth rings against a chronological chart developed by scientists to reflect each year's weather patterns in a specific geographical region reveals the age of the tree

Paint analysis

In 2008, a specialist analyzed the Marmion Room's paint history. Sixteen tiny paint samples from various locations in the room were looked at under high-powered magnification. The findings revealed that the Marmion Room was originally painted a deep yellow to match the adjacent rooms in the 1750s. A layer of decorative painting, visible today, was applied on top of the first generation of paint in the 1770s. Over the years, dirt and grime have accumulated, and the varnish has degraded. Consequently, the painted decoration seen in the room today is markedly browner and duller than it was when it was first applied.

Image: Cross-section of original deep yellow paint applied in the 1750s. Photograph courtesy of Susan L. Buck

Keep Learning

American Georgian Interiors (Mid-Eighteenth-Century Period Rooms)

Read more about American Georgian Interiors in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Art and Identity in the British North American Colonies, 1700–1776

Read more about art and identity in the British North American colonies in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.