Saint Agatha

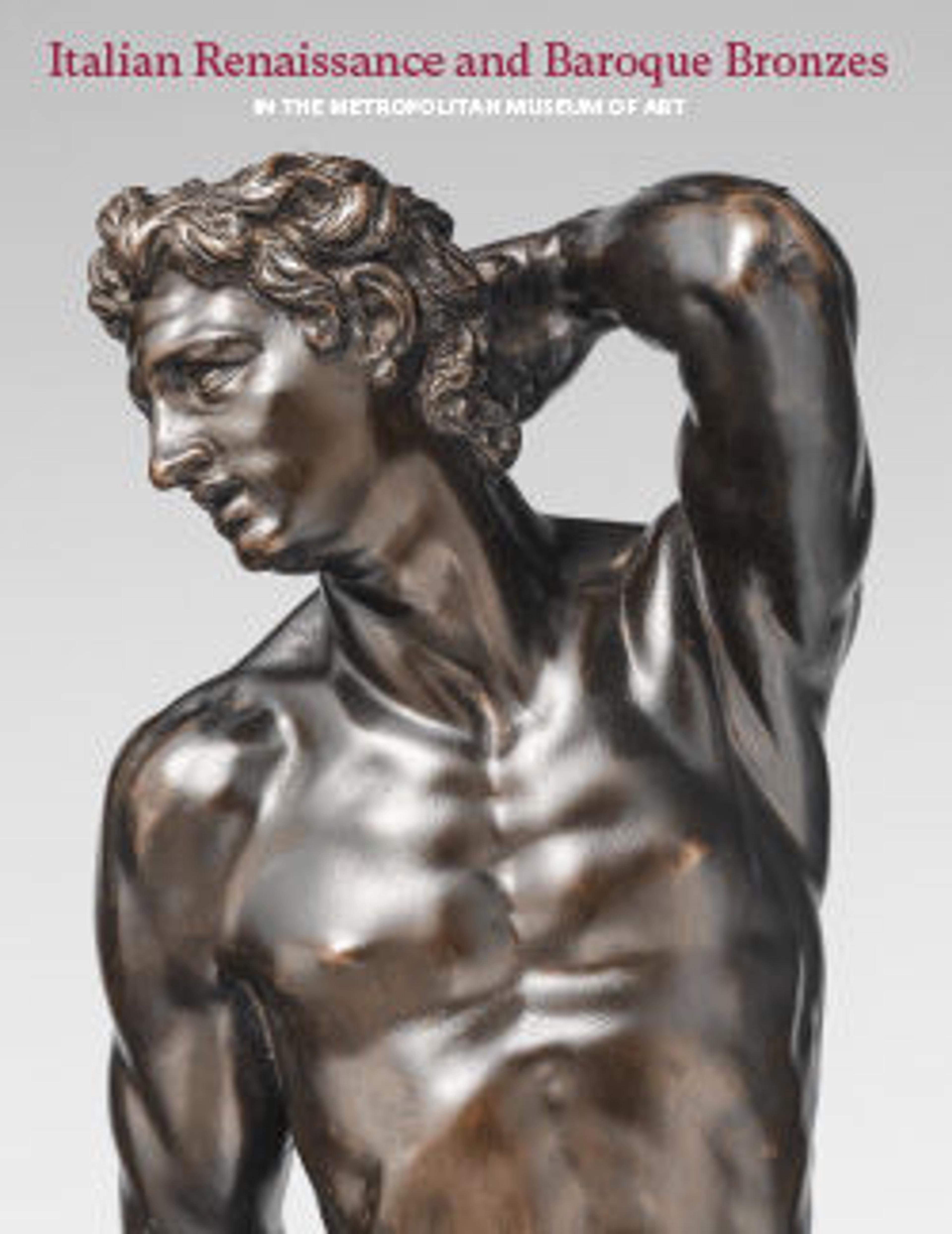

This small, half-length statuette depicts the early Christian saint Agatha gazing heavenward with her hands bound behind her back. According to legend, the Sicilian virgin-martyr died in the third century after a prolonged period of torture at the hand of the Roman prefect Quintianus. Among other ordeals, Agatha’s breasts were cut off with pincers; these body parts became the principal iconographic attribute of the saint in early modern representations (see, for example, Sebastiano del Piombo’s painting of 1520 in the Uffizi).

There are no other known casts of this model, which has not been discussed since 1910, when Wilhelm von Bode published it as “Italian, XVII century” in his catalogue of J. P. Morgan’s collection. The saint was indirectly cast in a high-copper alloy and shows traces of a previous black lacquer. Both breasts seem to have been prostheses, cast separately and soldered into place; only the right one remains.[1] This gruesome detail reflects the morbid seventeenth-century interest in the lives and deaths of early Christian martyrs. More specifically, the half-length composition, naturalistic details, and upturned eyes of our statuette align with contemporary paintings of female saints that were especially popular in Naples and produced by artists like Andrea Vaccaro.[2]

The bronze, which features a delicate floral patterning on Agatha’s dress, likely served a private, devotional purpose. A small hole at the back of the head suggests a missing halo. The probable date and place—Naples during the first half of the seicento—allows one to speculate that the bronze is linked to the renovation of the Palazzo di Sant’Agata by the powerful cardinal Cesare Firrao, who commissioned sculptors Bernardino Landini and Giulio Mencaglia to execute a series of statues for the facade (1637–44). Their figure of Magnanimity bears a resemblance to our bronze in its elegant elongated neck and elaboration of the coiffure.[3]

-JF

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. See R. Stone/TR, April 27, 2011. The right breast is a similar alloy with the same pattern of impurities as the rest of the statuette, but with the addition of lead, which has resulted in its slightly lighter color.

2. See, for example, the painting of Saint Agatha attributed to Vaccaro in the Museo Civico Gaetano Filangieri (Palazzo Como di Napoli).

3. For Cardinal Firrao, his palazzo, and his chapel in the church of San Paolo Maggiore, which features a marble statue of the Madonna by Mencaglia, see Iorio 2012, pp. 320, 328, and throughout

There are no other known casts of this model, which has not been discussed since 1910, when Wilhelm von Bode published it as “Italian, XVII century” in his catalogue of J. P. Morgan’s collection. The saint was indirectly cast in a high-copper alloy and shows traces of a previous black lacquer. Both breasts seem to have been prostheses, cast separately and soldered into place; only the right one remains.[1] This gruesome detail reflects the morbid seventeenth-century interest in the lives and deaths of early Christian martyrs. More specifically, the half-length composition, naturalistic details, and upturned eyes of our statuette align with contemporary paintings of female saints that were especially popular in Naples and produced by artists like Andrea Vaccaro.[2]

The bronze, which features a delicate floral patterning on Agatha’s dress, likely served a private, devotional purpose. A small hole at the back of the head suggests a missing halo. The probable date and place—Naples during the first half of the seicento—allows one to speculate that the bronze is linked to the renovation of the Palazzo di Sant’Agata by the powerful cardinal Cesare Firrao, who commissioned sculptors Bernardino Landini and Giulio Mencaglia to execute a series of statues for the facade (1637–44). Their figure of Magnanimity bears a resemblance to our bronze in its elegant elongated neck and elaboration of the coiffure.[3]

-JF

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. See R. Stone/TR, April 27, 2011. The right breast is a similar alloy with the same pattern of impurities as the rest of the statuette, but with the addition of lead, which has resulted in its slightly lighter color.

2. See, for example, the painting of Saint Agatha attributed to Vaccaro in the Museo Civico Gaetano Filangieri (Palazzo Como di Napoli).

3. For Cardinal Firrao, his palazzo, and his chapel in the church of San Paolo Maggiore, which features a marble statue of the Madonna by Mencaglia, see Iorio 2012, pp. 320, 328, and throughout

Artwork Details

- Title: Saint Agatha

- Date: mid-17th century

- Culture: Italian, probably Naples

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 5 3/8 × 3 1/2 × 3 1/8 in. (13.7 × 8.9 × 7.9 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931

- Object Number: 32.100.193

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.