Seated Hercules in the act of shooting at the stymphalian birds

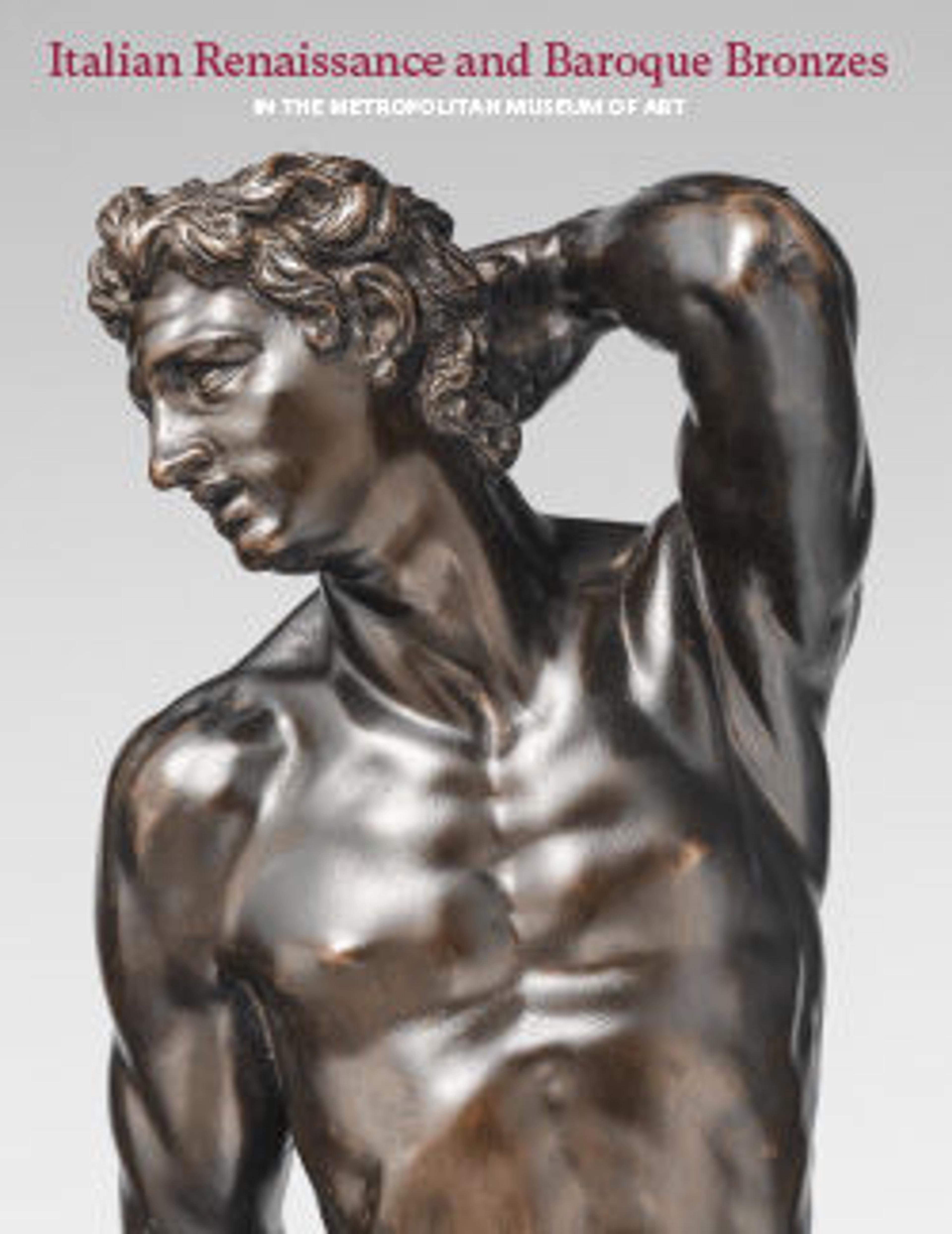

Seated with controlled torsion in his upper body, Hercules holds his left arm taut to raise a bow. Such an implement may once have fit into the hole between his thumb and fingers, and the force of his grasp engages his forearm and wrist tendons. Training his eyes toward his target, Hercules furrows his brow in concentration. Lips agape, he might be inhaling slowly, a customary breathing technique while drawing the bow to gather strength and focus the aim. Or he may be exhaling, his breath escaping as he lowers his right arm after firing a shot. Schematic tufts of hair frame his mouth with a close beard, an attribute of the ancient hero. Atop his left thigh rests a lionskin, the snout, ears, and eye sockets of the felled animal visible from above. Neglecting to hide Hercules’s nudity, the garment hugs his hip, inviting the viewer to follow its route to his left buttock. It is there, seen from behind, that one can admire the topography of Hercules’s flexed back muscles.

While this bronze and its subject telegraph fortitude, it has sustained significant damage. Over roughly half a millennium, it incurred breakages to both arms. The bent right arm was fractured below the elbow (which is itself original), and the existing forearm and hand are later replacements.[1] The left arm was broken at the bicep but subsequently reattached; the proper left index finger and big toe are missing. Both of the lower legs were filled with metal for cast-in repairs. Such vulnerabilities in the bronze were the result of its thin, even walls achieved through an indirect cast. The buttocks were filed down, which previously enabled the sculpture to nestle on a gently sloping stone base.[2] Because of this filing, it is unknown what kind of base the figure may have originally had, or whether it was originally balanced upright while seated on a flat surface, perhaps straddling the edge of a table or shelf.

With his powerful build, Hercules’s body is far from ordinary. This small bronze is clearly recognizable as an elaboration of the Belvedere Torso, a first-century B.C. marble statue bearing the signature of Apollonius in the Vatican Museums (fig. 51a).[3] Documented in Roman collections since around 1430, this 5 1/4-foot marble accrued particular fame in the early sixteenth century.[4] Presumably entering the Vatican collection during the papacy of Clement VII (r. 1523–34), the sculpture was installed in the Belvedere courtyard, joining one of the most celebrated assemblages of antiquities in existence.[5] Having spent part of its history in a sculptor’s collection in Rome, the Belvedere Torso also had a profound impact on the visual arts, appearing in various iterations in prints and sketchbooks, as well as inspiring the figural designs of artists including Michelangelo.[6] Unlike many other marble antiquities in the Renaissance, the Belvedere Torso was never restored, and the medium of small bronze offered an enduring means to elaborate its design in three dimensions beyond a fragmentary state.[7]

Renaissance collectors’ desire to own a miniaturized Belvedere Torso is evident through a number of surviving bronze variants. Some versions are minimal in their intervention, adding no limbs or simply a lower leg, while a group of others “restore” the sculpture to show Hercules seated and leaning on his club.8 All such versions have an integrated base evocative of the original marble. The Met’s bronze tilts the marble torso slightly backwards, endowing Hercules with a more upright posture to take aim. By showing him in the act of shooting a bow, it may be that our bronze links its famous prototype with a second marble in the same collection, the Apollo Belvedere. This sculpture of the shooting god was among the first antiquities reproduced in multiple small Renaissance bronzes, their maker the esteemed Gonzaga court artist Antico.[9] A multiplicity of prints based on the Apollo could also have assisted Renaissance viewers in connecting the Seated Hercules to his divine half-brother.[10]

Who or what is Hercules shooting? The hero discharged his bow on various occasions, including against the Hydra and Nessus, but our sculpture has always been identified with one subject since its first publication by Wilhelm von Bode in 1907: Hercules shooting the Stymphalian birds, his sixth labor.[11] Hercules’s defeat of the bronze-beaked, man-devouring fowl had precedent in programmatic representations of the labors in the Renaissance, but no other small bronzes of this subject are known to survive.[12] This was not for lack of available sources: the labor was found on ancient sarcophagi and coins, as well as in texts by writers ranging from Ovid, Seneca, and Statius to Renaissance humanists Cristoforo Landino and Angelo Poliziano. Other imagery of Hercules fueled greater artistic demand, such as his defeat of the giant Cacus, which gave rise to numerous small bronzes from the fifteenth century onward.[13]

The Seated Hercules’s unusual subject is best explained by associations between small bronzes and the pastoral in the Veneto during the sixteenth century. As Jodi Cranston has argued, small bronzes responded to a vogue for this genre both in their subject and their connections to collections and cultural programs in Venetian studioli.[14] While shepherds and nymphs were representative of the pastoral, the act of shooting the Stymphalian birds connected Hercules to this genre. In his Description of Greece (readily available to Renaissance audiences), Pausanias describes the territory of Stymphalus in the region of Arcadia on the Peloponnese peninsula, which contained a river of the same name:

There is a story current about the water of the Stymphalus, that at one time man-eating birds bred on it, which Heracles is said to have shot down. Peisander of Camira, however, says that Heracles did not kill the birds, but drove them away with the noise of rattles. The Arabian desert breeds among other wild creatures birds called Stymphalian, which are quite as savage against men as lions or leopards. . . . Whether the modern Arabian birds with the same name as the old Arcadian birds are also of the same breed, I do not know.[15]

Pausanias’s passage signals how Hercules’s sixth labor was continually linked to a specific region in Greece that was also associated with the setting of the pastoral.[16] By shooting the Stymphalian birds, the Seated Hercules invokes simultaneously the utopian and real region of Arcadia. While Arcadia loomed in the Venetian imaginary as a locus amoenus outside present concerns, it was also a physical place of immediate political interest for the Venetian empire as it challenged Ottoman expansion in Greece.[17] A labile hero that many Italian cities deployed for local political ends and endowed with Christian allegories, Hercules was seen as a protective figure in Venice, with two stone reliefs of the hero amid his labors prominently adorning the west facade of San Marco.[18] The owner of the Seated Hercules could have looked upon this bronze hero as a defender of the imagined Arcadian sanctuary in his private chambers, as well as the guardian of the Venetian Republic’s empire that would soon reach Arcadia itself.

But why is Hercules sitting? Written descriptions and images of the sixth labor give no justification for this posture. It may be a simple exigency of the choice to use the Belvedere Torso as a model. It could also link the sculpture to an additional subject, namely Odysseus revealing his identity to Penelope by shooting an arrow through a dozen axes, his neglect to stand proof of his singularly skillful marksmanship.[19] These possibilities are not mutually exclusive, and a third seems especially likely. A vibrant praise of a small bronze occurs in ancient texts by Martial and Statius, who describe a Hercules by the Greek sculptor Lysippos.[20] Statius writes:

Such was the dignity of the work, the majesty confined in narrow limits. A god he was, a god! And he granted you, Lysippus, to behold him, small to the eye but huge to the sense. The marvelous measure was no more than a foot, yet if you let your vision travel you will be fain to cry: “this was the breast that crushed the ravager of Nemea, these are the arms that bore the deadly club and broke Argo’s oars.” So mighty the deception that makes a small figure large. . . . A rough seat supports him, a stone adorned with Nemean hide.[21]

Hercules’s seated position in this famous passage may have guided the maker of our small bronze.[22] The sculptor thereby honored himself through the parallel to Lysippos, as well as the bronze’s owner, given Statius’s praise of the collector Novius Vindex, who set the ancient sculpture within an extensive household collection that enabled him to exhibit his knowledge.

The Seated Hercules must have been made by an artist with significant classical knowledge, or at least with ties to learned patrons. While Bode suggested the bronze derived from a work by Antico, at The Met it gained a more plausible attribution to the Venetian sculptor Vittore Gambello, since unchallenged in published scholarship.[23] This attribution was surely the result of John Pope-Hennessy’s ascription of a substantial number of small bronzes to him.[24] Gambello held the important post of master of the dies at the Venice Mint, and while he is well known for his medals, his skill as a bronze sculptor is evident in his signed relief of the Battle of Nude Men.[25] The relief is most similar to our bronze in the figures’ faces and hair, as well as the musculature of an archer seen from behind. Gambello’s status and evident family wealth suggest he engaged with the type of informed patron desirous of a bespoke bronze like the Seated Hercules.[26]

-RC

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Comments regarding the sculpture’s condition are guided by R. Stone/TR, April 28, 2008. Stone proposes a possible Paduan origin based on technical evidence that links the bronze to Riccio’s practice, including the minimal use of small, sheered iron core pins.

2. Seen in the earliest photos of the bronze, when it was in the collection of Walter von Pannwitz; Bode 1907–12, vol. 3, pl. CCXXXVII.

3. Langenskiöld 1930, p. 126; Andrén 1952.

4. Haskell and Penny 1981, pp. 311–14; Bober and Rubinstein 2010, pp. 181–84.

5. Ackerman 1954; Brummer 1970; Geese 1985; Winner et al. 1998; Christian 2010, pp. 265–75.

6. Schwinn 1973; Barkan 1999, pp. 189–201; Bober and Rubinstein 2010, pp. 182–84.

7. On the Belvedere Torso’s enduring state of fragmentation, see Schwarzenberg 2003. On small bronzes and the restoration of antiquities, see recently Parisi Presicce 2015. See also Sheard 1985, p. 432.

8. Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, 476; Bargello, Br. 342; Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid, 52.72.9; Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Bro. 46. See Beck and Bol 1985, pp. 44–45, 330–31.

9. Winner 1998; Kryza-Gersch 2011, p. 18.

10. For example, MMA, 49.97.114.

11. Bode 1907–12, vol. 3, p. 18. See further Langenskiöld 1930, p. 126; Schwinn 1973, pp. 50–51; Sheard 1979, cat. 57; Sheard 1985, p. 432; Beck and Bol 1985, p. 332.

12. Examples include Baldassare Peruzzi’s cycle in the Villa Farnesina and Albrecht Dürer’s surviving canvas in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, thought to be part of a series.

13. Wright 2005, pp. 334–48.

14. Cranston 2019, pp. 111–37.

15. Pausanias, Description of Greece, 8.22.4–6, trans. W. H. S. Jones and H. A. Ormerod (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1918), IV.

16. Arcadia was, no less, the title of one of the most important pastoral texts in the vernacular, Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia, first printed in 1504.

17. P. Brown 1996, pp. 80–81, 204–6; Davies and Davis 2007.

18. P. Brown 1996, pp. 21–23. On the political and cultural malleability of Hercules in Italy, see Wright 1994.

19. I thank Denise Allen for this compelling observation from books 19 and 21 of the Odyssey. 20. On this passage in relation to small bronzes in the Renaissance, see Kenseth 1998, pp. 129–30.

21. Statius, Silvae, IV.6, vv. 32–42, 56–58, trans. D. R. Shackelton Bailey (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 283–85.

22. The bronze identified as the Herakles Epitrapezios has been linked to the subject of the Belvedere Torso; see Zadoks-Jitta 1987.

23. Bode 1907–12, vol. 3, p. 18; New York 1973, cat. 22. Richard E. Stone, however, noted that the unusual core supports of the Seated Hercules are more akin to working processes in Padua following the work of Riccio, thereby casting some doubt on Gambello’s authorship. See R. Stone/TR, April 28, 2008.

24. Pope-Hennessy 1963a, pp. 22–23.

25. See, for example, Gambello’s signed medal of Giovanni Bellini, MMA, 23.280.32, and recently Matzke 2018, pp. 299–306. For the relief, see V. Avery 2011, p. 246.

26. V. Avery 2011, pp. 65, 366–67.

While this bronze and its subject telegraph fortitude, it has sustained significant damage. Over roughly half a millennium, it incurred breakages to both arms. The bent right arm was fractured below the elbow (which is itself original), and the existing forearm and hand are later replacements.[1] The left arm was broken at the bicep but subsequently reattached; the proper left index finger and big toe are missing. Both of the lower legs were filled with metal for cast-in repairs. Such vulnerabilities in the bronze were the result of its thin, even walls achieved through an indirect cast. The buttocks were filed down, which previously enabled the sculpture to nestle on a gently sloping stone base.[2] Because of this filing, it is unknown what kind of base the figure may have originally had, or whether it was originally balanced upright while seated on a flat surface, perhaps straddling the edge of a table or shelf.

With his powerful build, Hercules’s body is far from ordinary. This small bronze is clearly recognizable as an elaboration of the Belvedere Torso, a first-century B.C. marble statue bearing the signature of Apollonius in the Vatican Museums (fig. 51a).[3] Documented in Roman collections since around 1430, this 5 1/4-foot marble accrued particular fame in the early sixteenth century.[4] Presumably entering the Vatican collection during the papacy of Clement VII (r. 1523–34), the sculpture was installed in the Belvedere courtyard, joining one of the most celebrated assemblages of antiquities in existence.[5] Having spent part of its history in a sculptor’s collection in Rome, the Belvedere Torso also had a profound impact on the visual arts, appearing in various iterations in prints and sketchbooks, as well as inspiring the figural designs of artists including Michelangelo.[6] Unlike many other marble antiquities in the Renaissance, the Belvedere Torso was never restored, and the medium of small bronze offered an enduring means to elaborate its design in three dimensions beyond a fragmentary state.[7]

Renaissance collectors’ desire to own a miniaturized Belvedere Torso is evident through a number of surviving bronze variants. Some versions are minimal in their intervention, adding no limbs or simply a lower leg, while a group of others “restore” the sculpture to show Hercules seated and leaning on his club.8 All such versions have an integrated base evocative of the original marble. The Met’s bronze tilts the marble torso slightly backwards, endowing Hercules with a more upright posture to take aim. By showing him in the act of shooting a bow, it may be that our bronze links its famous prototype with a second marble in the same collection, the Apollo Belvedere. This sculpture of the shooting god was among the first antiquities reproduced in multiple small Renaissance bronzes, their maker the esteemed Gonzaga court artist Antico.[9] A multiplicity of prints based on the Apollo could also have assisted Renaissance viewers in connecting the Seated Hercules to his divine half-brother.[10]

Who or what is Hercules shooting? The hero discharged his bow on various occasions, including against the Hydra and Nessus, but our sculpture has always been identified with one subject since its first publication by Wilhelm von Bode in 1907: Hercules shooting the Stymphalian birds, his sixth labor.[11] Hercules’s defeat of the bronze-beaked, man-devouring fowl had precedent in programmatic representations of the labors in the Renaissance, but no other small bronzes of this subject are known to survive.[12] This was not for lack of available sources: the labor was found on ancient sarcophagi and coins, as well as in texts by writers ranging from Ovid, Seneca, and Statius to Renaissance humanists Cristoforo Landino and Angelo Poliziano. Other imagery of Hercules fueled greater artistic demand, such as his defeat of the giant Cacus, which gave rise to numerous small bronzes from the fifteenth century onward.[13]

The Seated Hercules’s unusual subject is best explained by associations between small bronzes and the pastoral in the Veneto during the sixteenth century. As Jodi Cranston has argued, small bronzes responded to a vogue for this genre both in their subject and their connections to collections and cultural programs in Venetian studioli.[14] While shepherds and nymphs were representative of the pastoral, the act of shooting the Stymphalian birds connected Hercules to this genre. In his Description of Greece (readily available to Renaissance audiences), Pausanias describes the territory of Stymphalus in the region of Arcadia on the Peloponnese peninsula, which contained a river of the same name:

There is a story current about the water of the Stymphalus, that at one time man-eating birds bred on it, which Heracles is said to have shot down. Peisander of Camira, however, says that Heracles did not kill the birds, but drove them away with the noise of rattles. The Arabian desert breeds among other wild creatures birds called Stymphalian, which are quite as savage against men as lions or leopards. . . . Whether the modern Arabian birds with the same name as the old Arcadian birds are also of the same breed, I do not know.[15]

Pausanias’s passage signals how Hercules’s sixth labor was continually linked to a specific region in Greece that was also associated with the setting of the pastoral.[16] By shooting the Stymphalian birds, the Seated Hercules invokes simultaneously the utopian and real region of Arcadia. While Arcadia loomed in the Venetian imaginary as a locus amoenus outside present concerns, it was also a physical place of immediate political interest for the Venetian empire as it challenged Ottoman expansion in Greece.[17] A labile hero that many Italian cities deployed for local political ends and endowed with Christian allegories, Hercules was seen as a protective figure in Venice, with two stone reliefs of the hero amid his labors prominently adorning the west facade of San Marco.[18] The owner of the Seated Hercules could have looked upon this bronze hero as a defender of the imagined Arcadian sanctuary in his private chambers, as well as the guardian of the Venetian Republic’s empire that would soon reach Arcadia itself.

But why is Hercules sitting? Written descriptions and images of the sixth labor give no justification for this posture. It may be a simple exigency of the choice to use the Belvedere Torso as a model. It could also link the sculpture to an additional subject, namely Odysseus revealing his identity to Penelope by shooting an arrow through a dozen axes, his neglect to stand proof of his singularly skillful marksmanship.[19] These possibilities are not mutually exclusive, and a third seems especially likely. A vibrant praise of a small bronze occurs in ancient texts by Martial and Statius, who describe a Hercules by the Greek sculptor Lysippos.[20] Statius writes:

Such was the dignity of the work, the majesty confined in narrow limits. A god he was, a god! And he granted you, Lysippus, to behold him, small to the eye but huge to the sense. The marvelous measure was no more than a foot, yet if you let your vision travel you will be fain to cry: “this was the breast that crushed the ravager of Nemea, these are the arms that bore the deadly club and broke Argo’s oars.” So mighty the deception that makes a small figure large. . . . A rough seat supports him, a stone adorned with Nemean hide.[21]

Hercules’s seated position in this famous passage may have guided the maker of our small bronze.[22] The sculptor thereby honored himself through the parallel to Lysippos, as well as the bronze’s owner, given Statius’s praise of the collector Novius Vindex, who set the ancient sculpture within an extensive household collection that enabled him to exhibit his knowledge.

The Seated Hercules must have been made by an artist with significant classical knowledge, or at least with ties to learned patrons. While Bode suggested the bronze derived from a work by Antico, at The Met it gained a more plausible attribution to the Venetian sculptor Vittore Gambello, since unchallenged in published scholarship.[23] This attribution was surely the result of John Pope-Hennessy’s ascription of a substantial number of small bronzes to him.[24] Gambello held the important post of master of the dies at the Venice Mint, and while he is well known for his medals, his skill as a bronze sculptor is evident in his signed relief of the Battle of Nude Men.[25] The relief is most similar to our bronze in the figures’ faces and hair, as well as the musculature of an archer seen from behind. Gambello’s status and evident family wealth suggest he engaged with the type of informed patron desirous of a bespoke bronze like the Seated Hercules.[26]

-RC

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Comments regarding the sculpture’s condition are guided by R. Stone/TR, April 28, 2008. Stone proposes a possible Paduan origin based on technical evidence that links the bronze to Riccio’s practice, including the minimal use of small, sheered iron core pins.

2. Seen in the earliest photos of the bronze, when it was in the collection of Walter von Pannwitz; Bode 1907–12, vol. 3, pl. CCXXXVII.

3. Langenskiöld 1930, p. 126; Andrén 1952.

4. Haskell and Penny 1981, pp. 311–14; Bober and Rubinstein 2010, pp. 181–84.

5. Ackerman 1954; Brummer 1970; Geese 1985; Winner et al. 1998; Christian 2010, pp. 265–75.

6. Schwinn 1973; Barkan 1999, pp. 189–201; Bober and Rubinstein 2010, pp. 182–84.

7. On the Belvedere Torso’s enduring state of fragmentation, see Schwarzenberg 2003. On small bronzes and the restoration of antiquities, see recently Parisi Presicce 2015. See also Sheard 1985, p. 432.

8. Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, 476; Bargello, Br. 342; Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid, 52.72.9; Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Bro. 46. See Beck and Bol 1985, pp. 44–45, 330–31.

9. Winner 1998; Kryza-Gersch 2011, p. 18.

10. For example, MMA, 49.97.114.

11. Bode 1907–12, vol. 3, p. 18. See further Langenskiöld 1930, p. 126; Schwinn 1973, pp. 50–51; Sheard 1979, cat. 57; Sheard 1985, p. 432; Beck and Bol 1985, p. 332.

12. Examples include Baldassare Peruzzi’s cycle in the Villa Farnesina and Albrecht Dürer’s surviving canvas in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, thought to be part of a series.

13. Wright 2005, pp. 334–48.

14. Cranston 2019, pp. 111–37.

15. Pausanias, Description of Greece, 8.22.4–6, trans. W. H. S. Jones and H. A. Ormerod (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1918), IV.

16. Arcadia was, no less, the title of one of the most important pastoral texts in the vernacular, Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia, first printed in 1504.

17. P. Brown 1996, pp. 80–81, 204–6; Davies and Davis 2007.

18. P. Brown 1996, pp. 21–23. On the political and cultural malleability of Hercules in Italy, see Wright 1994.

19. I thank Denise Allen for this compelling observation from books 19 and 21 of the Odyssey. 20. On this passage in relation to small bronzes in the Renaissance, see Kenseth 1998, pp. 129–30.

21. Statius, Silvae, IV.6, vv. 32–42, 56–58, trans. D. R. Shackelton Bailey (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 283–85.

22. The bronze identified as the Herakles Epitrapezios has been linked to the subject of the Belvedere Torso; see Zadoks-Jitta 1987.

23. Bode 1907–12, vol. 3, p. 18; New York 1973, cat. 22. Richard E. Stone, however, noted that the unusual core supports of the Seated Hercules are more akin to working processes in Padua following the work of Riccio, thereby casting some doubt on Gambello’s authorship. See R. Stone/TR, April 28, 2008.

24. Pope-Hennessy 1963a, pp. 22–23.

25. See, for example, Gambello’s signed medal of Giovanni Bellini, MMA, 23.280.32, and recently Matzke 2018, pp. 299–306. For the relief, see V. Avery 2011, p. 246.

26. V. Avery 2011, pp. 65, 366–67.

Artwork Details

- Title: Seated Hercules in the act of shooting at the stymphalian birds

- Artist: Vittore Gambello (Italian, Venice 1455/60–1537)

- Date: ca. 1515–20

- Culture: Italian, Venice

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 11 3/4 × 8 × 5 1/4 in. (29.8 × 20.3 × 13.3 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Gift of C. Ruxton Love Jr., 1964

- Object Number: 64.304.2

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.