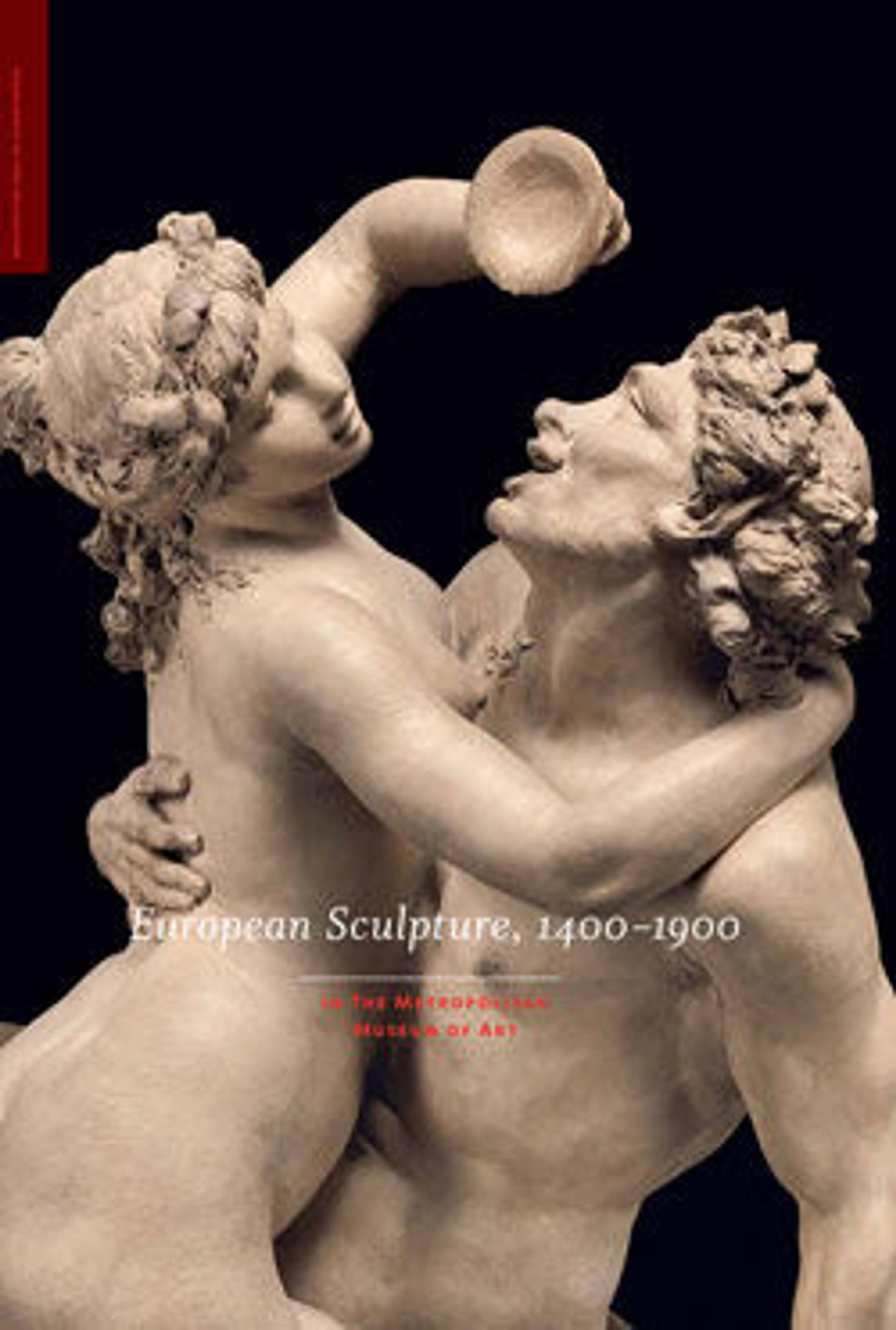

Andromeda and the Sea Monster

The opportunity to display a nearly naked damsel in distress pining for rescue was irresistible to many artists and patrons in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The first collector to whom this sculpture appealed was John Cecil, fifth Earl of Exeter, who evidently bought it on a trip to Rome. Cecil was one of the first Englishmen of his generation to collect Italian art on a grand scale. He acquired paintings by Luca Giordano and Carlo Maratta, commissioned Antonio Verrio and Louis Laguerre to paint frescoes at Burghley House, his manor in Stamford, and bought antiquities and contemporary sculpture.[2] Although the earl died on his way home to England in 1700, the sculpture safely completed the journey to Burghley House, where it was admired in various rooms, including the Gothic (or Great) Hall, until its removal sometime between 1957 and probably 1958.[ 3] While the identity of the patron is known, that of the sculptor was long mistaken. In the eighteenth century it was attributed to one of John Cecil’s favorite artists, Pierre-Étienne Monnot (1657 – 1733). That French sculptor, active in Rome and Kassel, met Cecil in 1699. The earl commissioned Monnot to carve his and his wife’s tomb, in the church of Saint Martin’s, Stamford (dated 1704), and acquired or commanded from him other works still at Burghley House.[4]

The attribution to Domenico Guidi, now generally accepted, was made only recently, by Andrea Bacchi.[5] The argument begins with a reminder of the first account of the Burghley House marble, based on a visit in 1727 by the antiquarian and engraver George Vertue, which includes the observation, "a fine Marble Statue. Andromeda. & Monster. Italian. carv’d by Dominico Guidi. cost 4000 crowns. at 5s 6d." [6] It was an antiquary from Stamford, Francis Peck, who in 1732 made the first written attribution of the Andromeda to Pierre-Étienne Monnot — probably because Monnot was the sculptor most firmly connected with Lord Exeter — and the error was perpetuated by subsequent authors. [7]

Bacchi also mentions the fact that Guidi had carved a marble Andromeda for Francesco II d’Este, Duke of Modena. In an exchange of letters in 1695 between Guidi and Rinaldo d’Este, Francesco’s successor, the sculptor stated that he had been commissioned to carve "in white marble the statue of an Andromeda tied to a rock in the act of being devoured by the monster" and requested payment for the finished work; but the new duke maintained that he could find no record of the commission.[8] Despite indications that Guidi was not paid, scholars assumed that the work mentioned in the Guidi-d’Este correspondence ended up in Modena because a marble Andromeda was recorded in the ducal palace there until 1771. Olga Raggio even proposed that Guidi’s presumed-lost work influenced the Metropolitan’s marble, which she, too, took to be by Monnot.[9] Bacchi also notes that Francesco II acquired a marble Andromeda carved by Orazio Marinali of Venice and proposes that this, rather than Guidi’s, was most probably the one that was in the palace at Modena. The likely scenario, then, is that John Cecil, visiting ateliers in Rome in 1699 – 1700, saw the unsold Andromeda in the workshop of Domenico Guidi and bought it. It may also be noted that Guidi likely made a modello, a smaller model in terracotta, for the marble, since there exists a bronze version in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy, and a lead version at Osterley Park, London, that must have been taken from it.[10]

Cecil would naturally have visited Guidi, who was the leading sculptor in Rome following the death of Gianlorenzo Bernini.[11] One of the most important works Guidi produced in the last decade of the seventeenth century was The Dream of Saint Joseph, a marble group on the altar of the Capocaccia Chapel in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome. The striking drapery patterns, the naturalistic carving of the rock base, and the angel’s stout limbs and classical features all bear a close relationship to those aspects of Andromeda and the Sea Monster, carved the year before The Dream of Saint Joseph was begun.

Guidi influenced a generation of French artists practicing in Rome, especially Monnot, who worked alongside him in the Capocaccia Chapel executing reliefs of the Adoration of the Shepherds and Flight into Egypt that flanked Guidi’s Saint Joseph group.[12] A comparison of Monnot’s reliefs — with their nervous line, minute drapery pleats, and sweet expressions — and Guidi’s group — with its more solid figures and broader treatment of cloth — clarifies the differences between the sculptors’ styles and places the Andromeda within the Italian master’s oeuvre.

Footnotes:

1. Domenico Guidi’s library contained a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It was inventoried there on April 16, 1701, after the artist’s death; see Archivio di Stato, Rome, Notario del Tribunale dell’Auditor Camerae, Notaio Marcus Josephus Pelusius, vol. 5636, 1701, fol. 152r – 164v (see Bershad 1970, p. 139). The story of Perseus and Andromeda is found in Metamorphoses 4.663 – 803. The quotation in this paragraph is taken from Ovid 1916 (ed.), vol. 1, p. 227.

2. See Honour 1958.

3. Horn 1797, pp. 182, 185. It was at Burghley House in July 1957 (records of the Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art, London), but Hugh Honour mentioned that he did not see it there in 1958.

4. See Pascoli 1730 – 36, vol. 2, pp. 491 – 92.

5. Bacchi 1994.

6. Vertue 1725 – 31/1931 – 32, p. 34.

7. Peck 1732 – 35, vol. 1, p. 45, "the finest white Marble I ever saw. It was done by the famous Peter Monot of Besancon." This attribution was followed in Harrod 1785, vol. 1, p. 291; Horn 1797, pp. 182 – 83; Hall 1858, n.p.; Castan 1887, pp. 134, 135; Lami 1906, p. 383; Brune 1912, p. 192; Réau 1931, pp. 148 – 49; Enggass 1976, p. 79.

8. Campori 1873, pp. 134 – 35.

9. Raggio 1977, pp. 371 – 72.

10. The bronze version measures 31 ½ by 27 ½ by 23 ⁵⁄8 inches (80 × 70 × 60 cm). On that version and the one at Osterley Park, see Sophie Harent in "Acquisitions" 2005, p. 84, no. 6 (Inv. 2003.14.1) and documents in the curatorial files of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum.

11. For Guidi, see Bershad 1970; Bershad 1996 (with bibliography).

12. Enggass 1976, p. 82; Ferrari and Papaldo 1999, pp. 352 – 53.

Artwork Details

- Title: Andromeda and the Sea Monster

- Artist: Domenico Guidi (Italian, 1625–1701)

- Patron: Commissioned by Francesco II, Duke of Mantua and Reggio (Italian, 1660–1694) , who died before the sculpture's completion

- Date: 1694

- Culture: Italian, Rome

- Medium: Marble

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 64 3/8 x 46 3/8 x 34 5/8 in. (163.5 x 117.8 x 87.9 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture

- Credit Line: Purchase, Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation Inc. Gift and Charles Ulrick and Josephine Bay Foundation Inc. Gift, 1967

- Object Number: 67.34

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Audio

2168. Andromeda and the Sea Monster

Ian Wardropper: This sculpture of a naked and chained young woman highlights the theatricality of late baroque style. As punishment for her mother's boasting, Andromeda has been chained to a rock to be devoured by a sea monster, presented quite spectacularly here at the left. As Andromeda twists and turns, she looks up hopefully, perhaps spotting her rescuer Perseus in the distance.

Depicting this crucial moment in the classical story intensifies the sense of drama, so emphasized in Baroque works. The sculptor, Domenico Guidi, worked in Rome at the end of the seventeenth century. James Draper, curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Art, points out how this single figure actively engages with the space it inhabits—a concept first explored by the great master sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

James Draper: It's a moment in the late Baroque, always inspired by Bernini, with these terrific diagonals and openings and sort of contradictory movements. The legs going one way, the head another with this extremely yearning expression. Flame-like movements, really.

Ian Wardropper: Baroque sculpture became highly prized by English collectors. This piece was acquired by John Cecil, the Fifth Earl of Essex, for his country house. It was displayed in the passage leading out to the garden.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.