Panel for a skirt or petticoat

Not on view

By the late seventeenth century, the appeal of Far Eastern goods and motifs had reached most levels of English society. Those who could not afford a cabinet mounted with imported Asian lacquer panels or a suite of tapestries like those produced by John Vanderbank (see MMA 53.165.2) could still satisfy their taste by wearing a petticoat or other fashionable accessory decorated with exotic motifs.

In 1688 John Stalker and George Parker published A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing, which includes twenty-four copperplate designs that could be used to decorate a variety of objects (see MMA 32.80.2). This book also gives detailed instructions on how to create imitation lacquer, or japanning, on various household objects. The text shows a lack of specificity regarding culture and geography that was typical of the period. For example, in their preface, the authors sing the praises of Japan and its architecture, but in the instructions the reader is advised "that if you would exactly imitate and copie [sic] out the Japan [design for imitation lacquer]" one should look to "the true Indian work" where they "never crowd up their ground with many Figures, Houses, or Trees, but allow great space to little work."¹

There are extant English mirrors that retain their original "Japanned" frames, as well as American furniture decorated with motifs from works like A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing.[2] However, such books inspired more than just imitation lacquer on furniture. This embroidered panel and its mate are among a number of English examples from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries that are stitched with similar exotic designs. A small quilt in the Metropolitan Museum and two panels in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, are all embroidered with the motifs of the woman carrying a fan with an attendant who shades her with a parasol, and tiny pavilions dwarfed by oversize foliage.[3] One of the panels in Boston bears the rare signature of a professional pattern draftsman, one John Stilwell who had a shop near Covent Garden, London. Stilwell would have drawn his designs directly on fabric that was then embroidered; for inspiration he probably relied on publications such as A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing.

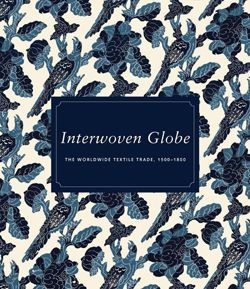

[Melinda Watt, adapted from Interwoven Globe, The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800/ edited by Amelia Peck; New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: distributed by Yale University Press, 2013]

Footnotes

1. Stalker and Parker, A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing . . . 1688, pp. xv, 40.

2. See, for example, a Connecticut chest of drawers, dated 1735–50, in the Metropolitan Museum, acc. no. 45.78.3; Safford, American Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 1, Early Colonial Period, pp. 275–78, no. 112.

3. See Metropolitan Museum, acc. no. 40.25, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (nos. 43.259 and 1995.5). The latter (1995.5) is inscribed in ink on the fabric: John Stilwell Drawear at Ye Flaming Soord [sword] Rusill Street Covint Garden Remoove at Quartear-Day 2 ye [3?] Pidgins in halfe moone sreet.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.