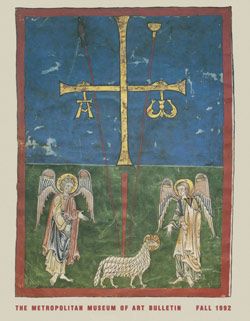

Cylinder seal and modern impression: royal worshiper before a god on a throne; human-headed bulls below

Not on view

Although engraved stones had been used as early as the seventh millennium B.C. to stamp impressions in clay, the invention in the fourth millennium B.C. of carved cylinders that could be rolled over clay allowed the development of more complex seal designs. These cylinder seals, first used in Mesopotamia, served as a mark of ownership or identification. Seals were either impressed on lumps of clay that were used to close jars, doors, and baskets, or they were rolled onto clay tablets that recorded information about commercial or legal transactions. The seals were often made of precious stones. Protective properties may have been ascribed to both the material itself and the carved designs. Seals are important to the study of ancient Near Eastern art because many examples survive from every period and can, therefore, help to define chronological phases. Often preserving imagery no longer extant in any other medium, they serve as a visual chronicle of style and iconography.

The modern impression of the seal is shown so that the entire design can be seen. The main scene depicts a worshiper offering a caprid to a divinity seated above two human-headed bulls. The god is enthroned on a stool with animal legs of a type known from actual contemporary remains in wood and ivory from both Egypt and Anatolia. in the field between them are a winged rosette disk with crescent, two stars, a squatting monkey, and an ankh, the Egyptian symbol for life. A sphinx wearing an Egyptian crown attacking an ibex is also depicted above a guilloche and a kneeling griffin-demon in a flounced skirt.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.