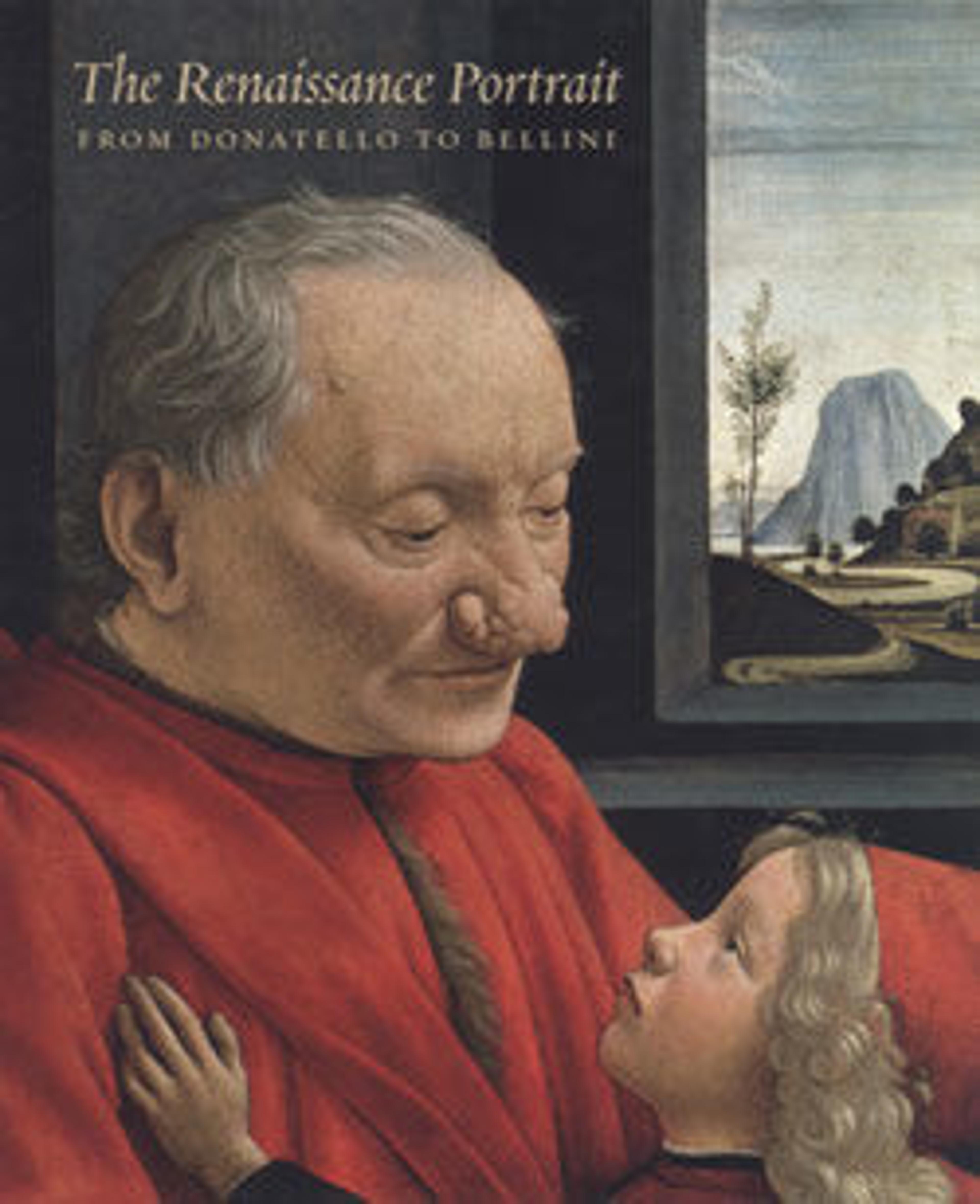

Portrait of a Young Man

This confident young Florentine, perhaps fifteen or sixteen years old, stands before the valley of the Arno river with Florence’s city walls and cathedral in the distance. Aristocratic parents typically commissioned portraits of their sons to mark a special occasion and to celebrate them as heirs—the budding masculinity and authoritative bearing of this unknown adolescent project his suitability for this role. Biagio specialized in works for domestic interiors, including painted wood panels (spalliere) and marriage chests (cassone), an example of which is on view nearby. This is one of just three known portraits by the artist; each depicts a young man before a landscape.

Artwork Details

- Title: Portrait of a Young Man

- Artist: Biagio d'Antonio (Italian, Florentine, active by 1472–died 1516)

- Date: probably ca. 1470

- Medium: Tempera on wood

- Dimensions: Overall 21 3/8 x 15 1/2 in. (54.3 x 39.4 cm); painted surface 20 1/4 x 14 1/4 in. (51.4 x 36.2 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931

- Object Number: 32.100.68

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.