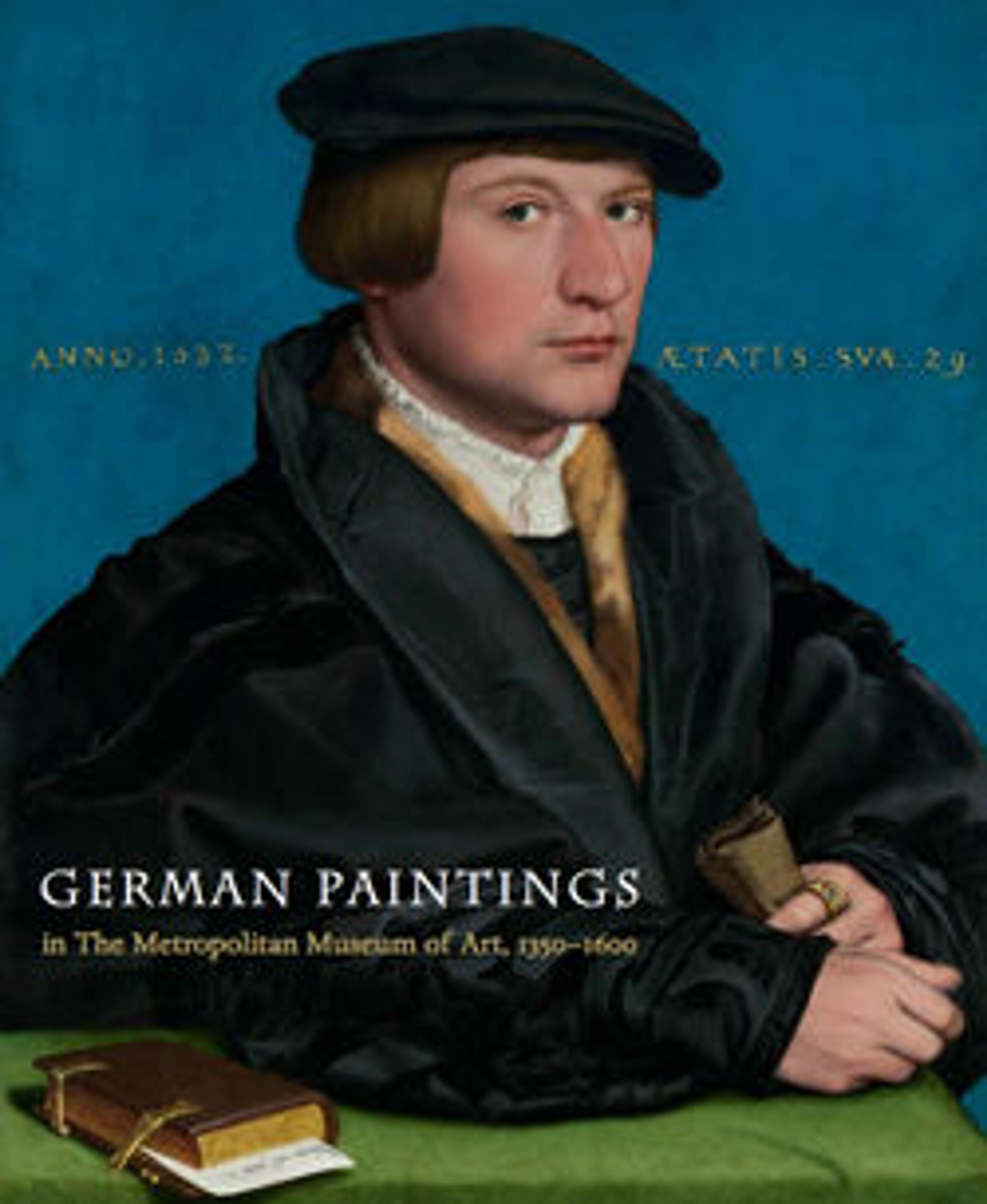

Derick Berck of Cologne

This painting belongs to a group of portraits Hans Holbein made for the German merchants of the Hanseatic League in London (see also his Portrait of a Member of the Wedigh Family nearby). The bearded, thirty-year-old sitter is identified by the letter in his hand, which is addressed "To the honorable and pious Derick Berck, London, at the Steelyard [. . .]." The other inscription on the cartellino refers to a passage from Virgil’s Aeneid that reads, "[Perchance even this distress] will someday be a joy to recall." Exhorting perseverance, this statement might have been the sitter’s personal motto.

Artwork Details

- Title: Derick Berck of Cologne

- Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger (German, Augsburg 1497/98–1543 London)

- Date: 1536

- Medium: Oil on canvas, transferred from wood

- Dimensions: 21 x 16 3/4 in. (53.3 x 42.5 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Jules Bache Collection, 1949

- Object Number: 49.7.29

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.