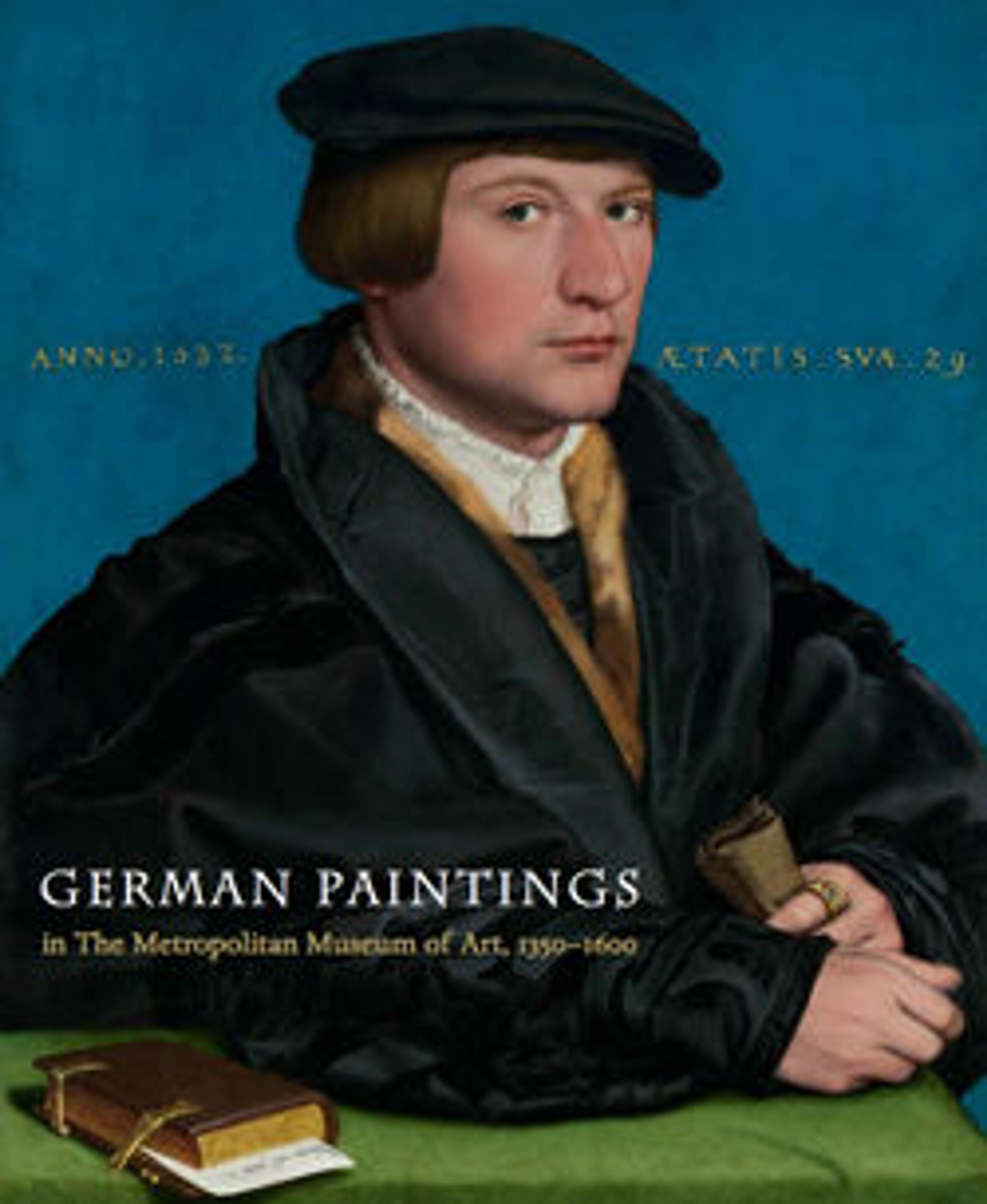

Edward VI (1537–1553), When Duke of Cornwall

Edward, the sole legitimate son of Henry VIII, was born on October 12, 1537 and crowned Edward VI in 1547. This portrait shows the future king at age six, when he was still the Duke of Cornwall. It was subsequently adapted in costume to reflect Edward’s stature at the time of his coronation. The roundel format and the sitter’s profile pose evoke the coinage of classical antiquity, admired at the Tudor court. The panel was once considered an autograph work by Holbein. Technical evidence, however, suggests it was painted after his death by a workshop assistant, based on an earlier design by the master.

Artwork Details

- Title: Edward VI (1537–1553), When Duke of Cornwall

- Artist: Workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger

- Date: ca. 1545; reworked 1547 or later

- Medium: Oil and gold on oak

- Dimensions: Diameter 12 3/4 in. (32.4 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Jules Bache Collection, 1949

- Object Number: 49.7.31

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.