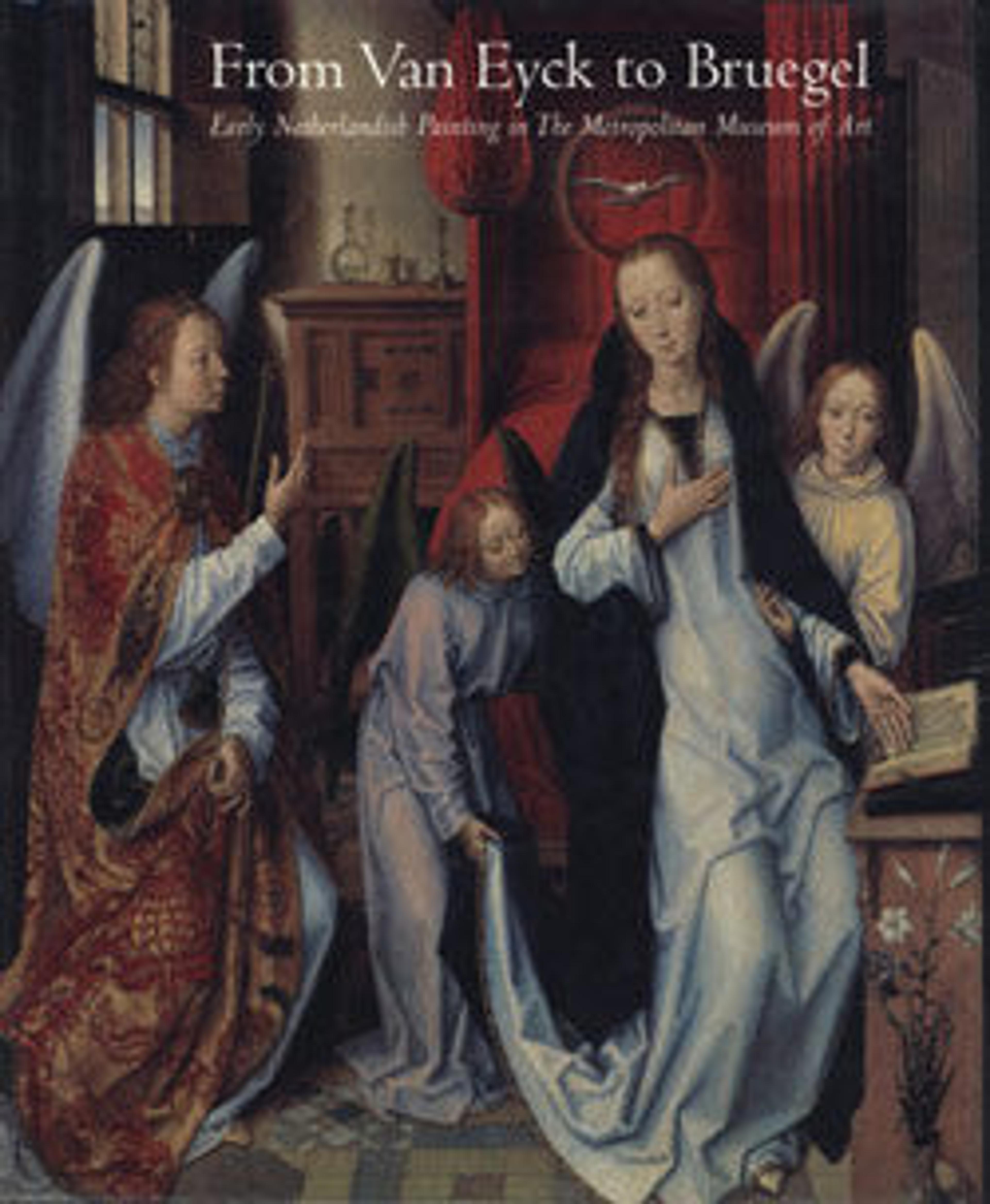

The Adoration of the Christ Child

The fourteenth-century mystic Saint Bridget of Sweden recounted Christ's birth after experiencing a vision. The "great and ineffable light" she described as emanating from the Child is the most compelling feature of this picture. The portrayal of this divine splendor allowed painters to convey the mystical aura of the event and to experiment with dramatic lighting effects. Drawings and numerous paintings of the subject suggest that a lost work by Hugo van der Goes was the source of the composition. A variation on the theme, produced by a different workshop, also belongs to the Museum (Robert Lehman Collection).

Artwork Details

- Title: The Adoration of the Christ Child

- Artist: Follower of Jan Joest of Kalkar (Netherlandish, active ca. 1515)

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: Overall 41 x 28 1/4 in. (104.1 x 71.8 cm); painted surface 41 x 27 5/8 in. (104.1 x 70.2 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982

- Object Number: 1982.60.22

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.