The Painting and its Commission: The Marriage Feast at Cana is a theme not frequently encountered in early Netherlandish painting, except for cycles representing the miracles of Christ. Only the Gospel of St. John 2:1–11 relates Christ’s first miracle that occurred as he and his Mother, the Virgin Mary, attended a wedding feast. During the celebrations, Mary noticed that the wine was depleted, and turned to her son (at the far left of the table) for a solution. Christ instructed the servants to fill the empty jugs with water, but when the liquid was subsequently poured, it had been changed into the highest quality wine. Upon sampling the wine, the steward remarked to the bridegroom on his unconventional choice of serving the finest wine at the end rather than the beginning of the feast. This painting represents the moment the miracle occurred. As a servant pours water into a jug in the foreground, Christ raises his right hand in blessing, effecting the conversion of water into wine. Mary lovingly looks at her son and with hands raised in a prayerful attitude, acknowledges the miracle taking place. Behind the servant stands the wine steward, holding a large golden covered cup topped by a red gemstone, from which he will offer the miraculous drink to the bridal couple. The bridegroom and his bride are engaged in a thoughtful exchange, while a man viewed between the columns at the left directly addresses the viewer.

The composition is simplified to the bare minimum of figures necessary for the theme. During the Middle Ages, the wedding at Cana was often believed to represent that of John the Evangelist to Mary Magdalen,[1] thereby emphasizing piety and marital chastity. In fact, Queen Isabella I of Castile’s 1505 inventory describes The Met painting as “the marriage of Saint John” (Sanchez Canton 1930), and the groom’s appearance conforms to conventional, idealized images of John in which he is beardless and wears a red robe and cloak. It has also been suggested that the married couple may be disguised portraits of Isabella’s son, Prince Juan, and daughter-in-law, Margaret of Austria, on the occasion of their marriage on April 3, 1497, barely a month after Margaret had arrived in Burgos. The bride, like Margaret of Austria, has blond hair, and a rather narrow face with prominent nose. Furthermore,

margaritas, a daisy-like flower, adorn the diadem she wears and the jeweled clasps of her mantle (Ishikawa 2004, p. 92). John the Evangelist was Isabella’s patron saint as well as the Prince Juan’s namesake, supporting the notion that the prince joins Margaret here as a disguised portrait.[2]

Carl Justi (1887) listed this painting as one of a group of forty-seven small painted panels representing the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary in the February 25, 1505 inventory of Queen Isabella the Catholic at the castle of Toro. As Justi noted (also Reynaud 1967), the list is missing some important scenes, among others, the Resurrection and Christ Washing the Feet of the Apostles, indicating that the project may have been left incomplete at the death of Queen Isabella in 1504. Alternatively, a few panels could have been lost before the inventory was recorded. The document describes the paintings as being "en un armorio" (in a cupboard), suggesting that the series was not framed as a unit. A number of the panels, including The Met’s, had gilded borders, serving as fictive frames.[3] This would have encouraged each to be handheld or arranged in groups for private devotion.

After Isabella’s death, thirty-two of the panels, including the Cana scene, were bought by Diego Flores, treasurer of Margaret of Austria, and brought to Mechelen where they were recorded in Margaret’s collection in 1516.[4] It was there that Albrecht Dürer first encountered the panels and commented in his diary in 1521 on their "purity and quality" (Muller 1918). By 1524 only twenty-two of the panels were still in Margaret’s palace in Mechelen. She selected eighteen of the narrative scenes, and in 1527 had them mounted in a diptych format with an elaborate silver-gilt frame, all topped by

The Marriage Feast at Cana and

The Temptation of Christ (National Gallery of Art, Washington). Ishikawa’s reconstruction (2004, p. 13, fig. 4), based on the framing order in the inventory in 1600 of a subsequent owner, Philip II, shows nine scenes on each wing. The two groupings could be read from left to right and top to bottom. Nail holes in the corners and at the sides of The Met’s panel and others in the group likely resulted from that installation.

Margaret of Austria’s decision to install the panels together in an elaborate frame may have had something to do with the lack of any possibility of a complete and unified presentation of the remaining panels. Joined together in a new ensemble, they were perhaps more impressive for their stunning style and execution (Ishikawa 2004, p. 15). It cannot be a coincidence that it was at this time that the diptych was moved from the Regent’s bedroom—her locus of daily private devotions—to her

riche cabinet where the most impressive pieces of her collection were installed for the enjoyment of visitors (Eichberger 2002, pp. 241–43; Ishikawa 2004, p. 15). The placement of

The Marriage Feast at Cana and

The Temptation of Christ at the peak of the two wings of the diptych may have been intended to signal “their embodiment of Christ’s simultaneous human and divine nature: the

Marriage Feast at Cana is the first demonstration that the man has divine powers; while the

Temptation of Christ is the first test of God for human weakness” (Ishikawa 2004, p. 15). Below this first miracle of Christ in

The Marriage Feast at Cana are additional scenes of his teachings and miracles.

However, there may be other more personal reasons for Margaret having featured

The Marriage Feast at Cana in such a way. Eichberger noted that the Regent commissioned and retained an unusually large number of themes that feature female protagonists.[5] Mary Magdalene is conspicuous in five of the scenes—

The Marriage Feast at Cana,

The Penitence of Mary Magdalene,

The Raising of Lazarus,

The Three Maries at the Tomb,

Noli Me Tangere—the latter four of which are prominently displayed across the central row of Margaret’s diptych. Moreover, as discussed above,

The Marriage Feast at Cana, at the peak of the diptych’s left wing, likely shows a disguised portrait of Margaret as the bride, with Prince Juan as the bridegroom (Ishikawa 2004, p. 15). This then would constitute a prominent display of the sanctity of the Regent’s marriage to Juan and their piety.

The painting is in good condition and intact with all of its original edges. There are remnants of an apparently original gold border and nail holes at all four corners and at the mid-points of each side. The jewel-like paint surface is fairly well preserved, except for some abrasion to the upper paint layers and the repainted right eye of the bride over a knot in the wood. Over time, some of the paint layers have become more transparent, allowing the underdrawing to show through, visible to the naked eye.

The Artist and Date: Carl Justi (1887) was the first to connect the forty-seven small panels of the life of the Virgin and Christ in Isabella of Castile’s 1505 inventory with Juan de Flandes, documented as the Queen’s court painter from 1496 until her death in 1504. He further made the stylistic link between the fifteen remaining panels in Madrid (Museo del Palacio Real) and the eleven documented panels Juan de Flandes painted for the

Retablo Mayor in Palencia Cathedral.[6] There have been various opinions about the authorship of the panels comprising Isabella’s series of the life of the Virgin and Christ—to Juan de Flandes, Michel Sittow, and possibly Felipe Moros (Ishikawa 1989, 2004; Silva Maroto 2006; Weniger 1994, 2011). However, the attribution of The Met’s painting to Juan de Flandes has only found one dissenting voice, assigning the authorship to an anonymous Netherlandish master (see References and V[ernon] J. W[atney] 1915).

As is the case with the series in general, The Met’s painting exhibits a conflation of Netherlandish and evolving Spanish painting styles. Probably trained in Ghent and Bruges, Juan de Flandes comes out of a tradition of miniature painters whose skills were tailormade for paintings on a diminutive scale and intended to be filled with meticulously rendered details of figures and their settings. Although Juan de Flandes later proved that he could adapt completely to the Spanish style of painting (see

58.132), while he worked as a court artist for Isabella of Castile, he maintained the Flemish style so admired by Isabella, and for which she had hired him to work at her court. The kind of narrative detail exemplified in the

Marriage Feast both in design and in scale is equivalent to the best illuminated books produced for royal patrons. The close-up view of figures in intimate architectural spaces found in the

Breviary of Isabella of Castile (British Library, London; see figs. 1, 2 above), presented to the Queen shortly before 1497 by the Spanish Ambassador Francisco de Rojas, offers a devotional counterpart to the individual scenes painted by Juan de Flandes in the series of the lives of Christ and the Virgin.[7]

However, Juan’s habitual inclination to fill his compositions with all kinds of details was mediated by his patron and perhaps her spiritual advisor, Hernando Talavera, who likely influenced the final design toward a certain sense of psychological restraint and austerity. This can be detected in Juan’s working procedures for the painting. The composition in general is derived from those of the theme painted by Bruges artists such as Gerard David, possibly in an earlier version of his

Marriage Feast at Cana (Musée du Louvre, Paris; fig. 3) as it postdates Juan’s painting by several years (Bauman 1984, pp. 63–64).[8] The room is laid out in similar fashion with the open colonnade at the left, the table occupying the center and right, similarly-shaped stone jugs in the foreground, and the attendees seated around the table with Christ at the left, blessing the water to be turned into wine.

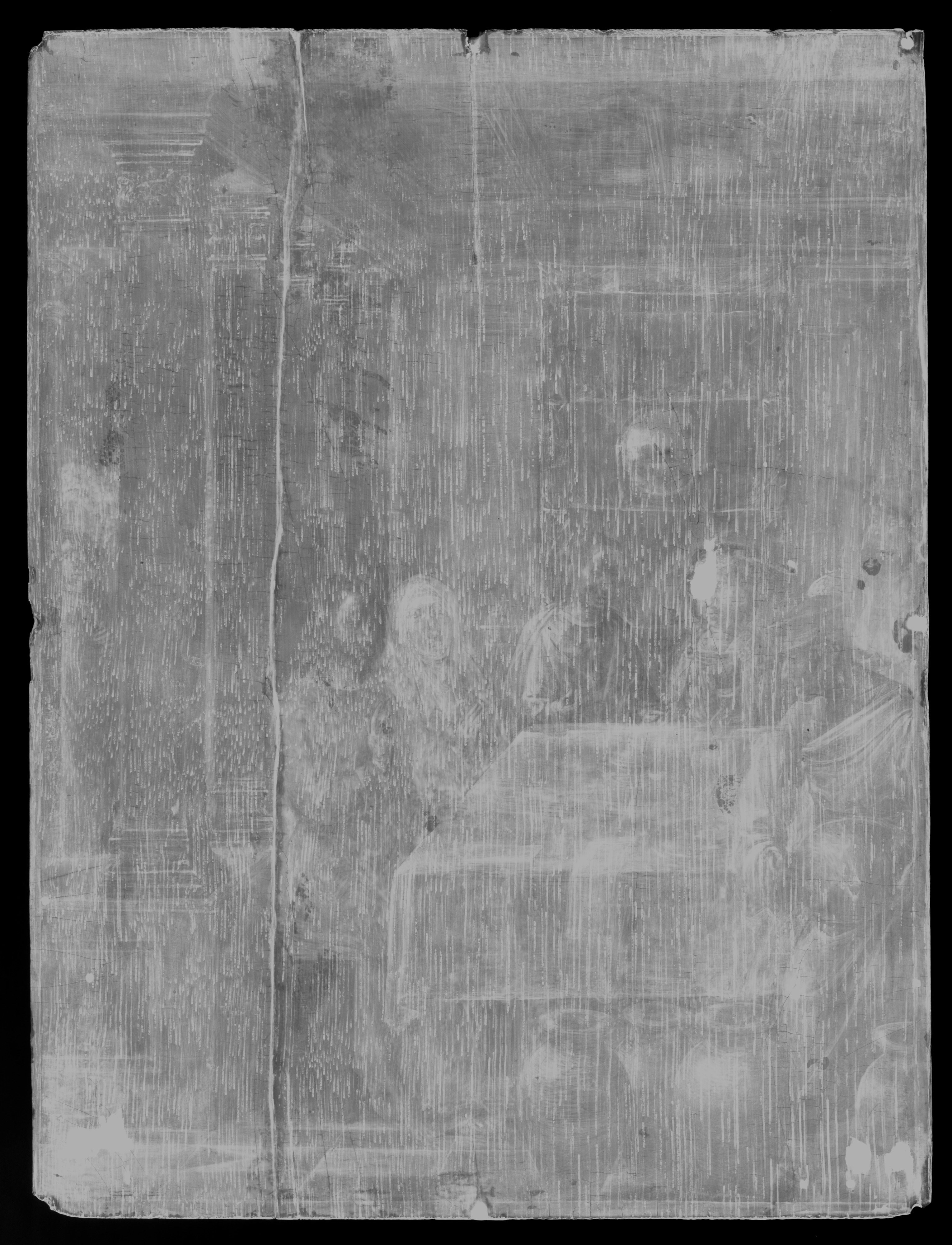

Examination with infrared reflectography (fig. 4) has revealed numerous changes made from the underdrawing to the painted layers. These changes converted what was initially planned as a composition filled with charming incidental details into a reduction of these to the bare minimum required. The underdrawing, some of which is visible to the naked eye, was carried out in two stages: a rough sketch in a black crumbly medium, probably black chalk, gone over with a quill pen in a liquid medium. In some places Juan used tiny dots of the liquid medium to mark the edges of forms, an aspect of execution that is characteristic of his underdrawings (Ainsworth 2008). Originally in place of the brick wall with the gold–trimmed, green cloth of honor and convex mirror, Juan first designed an open archway flanked with putti blowing trumpets or holding festive swags, such as one finds in paintings by Hans Memling (e.g., the

Triptych with the Virgin and Child Enthroned, of about 1480–88 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) or Gerard David (e.g., the

Triptych with the Virgin and Child Enthroned, of about 1490–95 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). The table was filled with plates, napkins, a knife, possibly another loaf of bread, and a large charger in the middle. In place of the potted plant at the lower left was a small dog, sniffing curiously at the ground. These are all the kind of features that a typically Flemish marriage feast would include. Here, however, the painted version is stripped down to the bare essentials. While this may have been an aesthetic choice to coordinate the

Marriage Feast with other paintings of the series, the new directness and simplicity of the composition may also have been in keeping with the court milieu (Ishikawa 2004, p. 25–26). The austere style of presentation complemented the Queen’s approach to religious matters, as expressed above all by her spiritual advisor, Fray Hernando de Talavera, the Archbishop of Granada and the Queen’s confessor (Ishikawa 2004, pp. 26–33).

Some other changes made from the underdrawing to the painted surface imply the possible intervention of Isabella in tailor-making the scene in more personal ways. Notably, the bride, who has been identified as a disguised portrait of Margaret of Austria (see above), was underdrawn with a plain veil, while in the painted version her blond hair is adorned with a diadem of

margaritas and her mantle with jeweled clasps of the same flower to support the identification of her as Margaret. In addition, the bride adopts a devout manner with the prayerful gesture of her hands. John responds as if holding an object—a no-longer visible ring?—in his right hand, another feature that is not prepared in the underdrawing but only appears in the painted layers. Finally, the male figures at the far left and far right were not underdrawn but added late in the paint stages. They appear portrait–like, and one wonders whether they could be images of a court advisor, such as Talavera at the left, or a self–portrait of the artist at the right.

If

The Marriage Feast at Cana in part commemorates the union of Prince Juan and Margaret of Austria, then it may have been painted around the time of their wedding on April 3, 1497, but before October 4, 1497, when Prince Juan unexpectedly died. This panel then would have been among the earliest produced in the series.

Maryan W. Ainsworth 2022

[1] Saint Jerome is credited with the identification of Saint John the Evangelist as the bridegroom at the Marriage Feast at Cana; see Gertrud Schiller,

Iconographie der christliche Kunst, 5 vols., Gütersloh, 1986, vol. 1, p. 164.

[2] This conforms to the practice during this time in Castile of including royal portraits within religious scenes as participants or in the guise of various key protagonists. Isabel is portrayed as a servant in Juan de Flandes’

Birth and Naming of John the Baptist (Cleveland Museum of Art), and among the multitude in the

Miracle of Loaves and Fishes, part of the

Retablo de Isabel la Católica (Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid). Furthermore, Michel Sittow apparently included Margaret of Austria and Prince Juan as Saint Margaret and Saint John as part of a lost diptych that was listed in Margaret’s 1516 inventory. See Ishikawa 2004, pp. 92, 161 n. 36.

[3] Lorne Campbell,

The National Gallery Catalogues, The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools, London, 1998, p. 264.

[4] For a detailed description of history of the forty-seven panels and their various owners, see Campbell 1998, pp. 262, 264.

[5] Dagmar Eichberger, “Die Sammlung Margarete von Ősterreichs,” Unpublished

Habilitationsschrift, 1999.

[6] For which, see Ignace Vandevivere,

La Cathédrale de Palencia et l’Église Paroissiale de Cervara de Pisuerga, Brussels, 1967, pp. 1–81, pls. I–CLXXVII.

[7] See Thomas Kren and Maryan W. Ainsworth in Thomas Kren and Scot McKendrik,

Illuminating the Renaissance, The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, exh. cat., J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2003, pp. 347–51, no. 100. See also Jennings 2021 for the relationship of Isabella’s life of Christ and the Virgin to manuscript illumination.

[8] Hans van Miegroet,

Gerard David, Antwerp, 1989, pp. 203, 207, 209, no. 42, pp. 307–8.