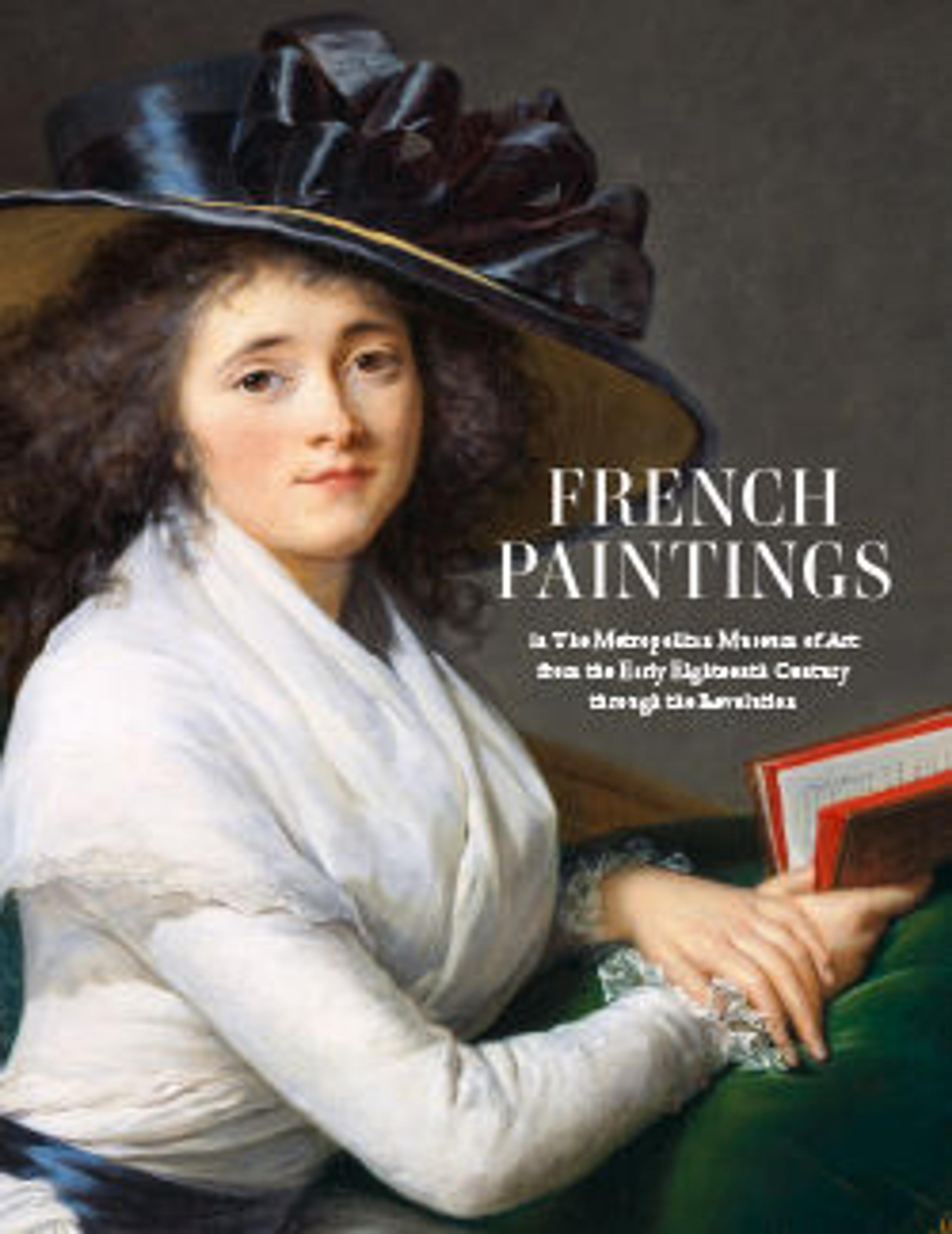

The Interior of a Woman Painter's Studio

Although she painted this work in 1789, Lemoine could not exhibit it at the prestigious Paris Salon until 1796, when post-Revolutionary reforms greatly expanded women artists’ access to the official art world. The title suggests an ideal or generic depiction of women artists, but those close to Lemoine recognized a self-portrait with her sister Marie Elisabeth, who was also a painter. Lemoine’s skills in still life and portraiture, categories in which women most often trained, are readily visible, but a history painting—the highest category in the academic system and usually considered in this period as ill-suited to women—is underway on the easel in the scene.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Interior of a Woman Painter's Studio

- Artist: Marie Victoire Lemoine (French, Paris 1754–1820 Paris)

- Date: 1789

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 45 7/8 x 35 in. (116.5 x 88.9 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Gift of Mrs. Thorneycroft Ryle, 1957

- Object Number: 57.103

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.