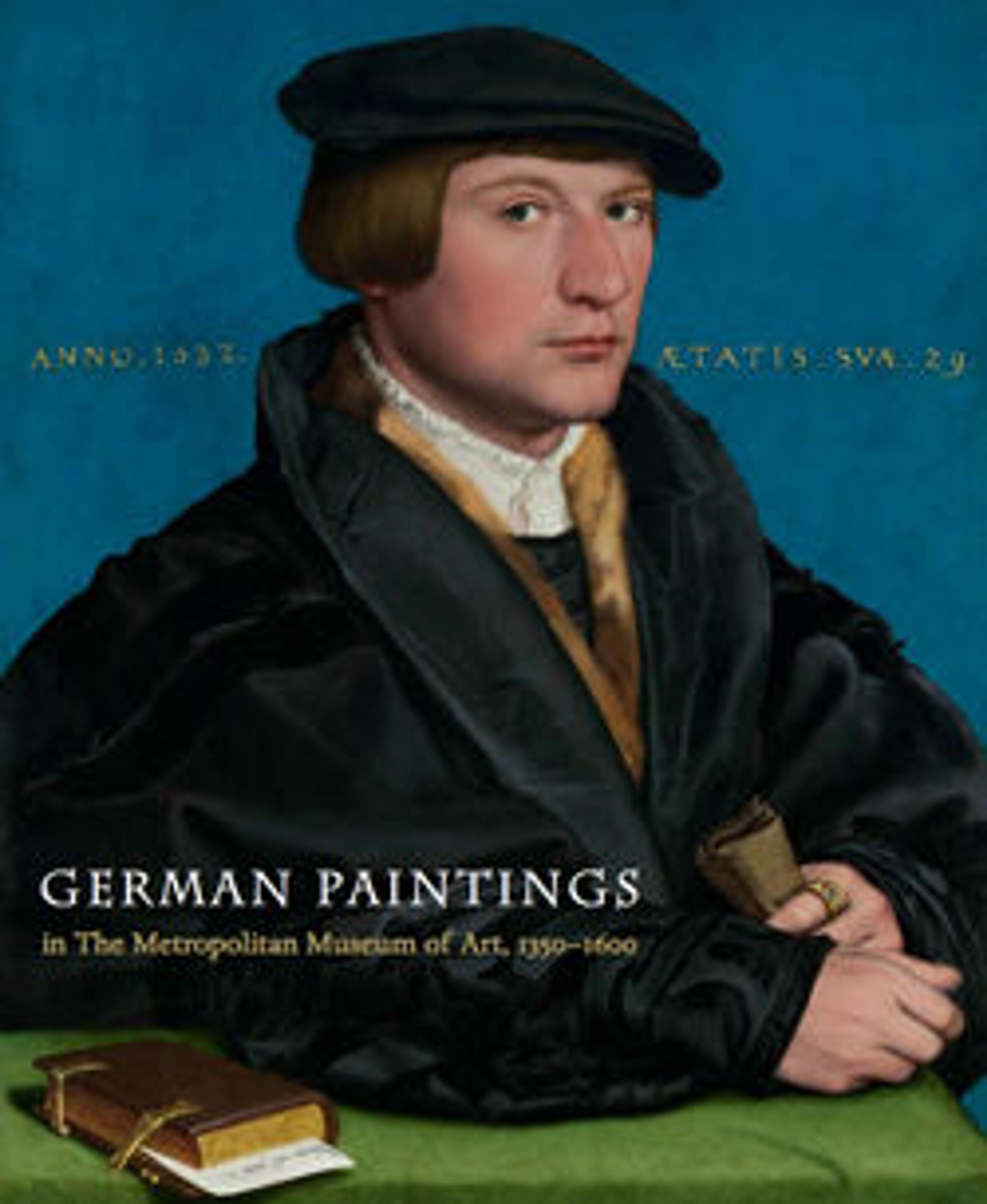

The Dormition of the Virgin; (reverse) Christ Carrying the Cross

Despite its monumental size, this large, double-sided panel is actually a fragment that was once one of four wings of a folding triptych. Its panels represented scenes from the Passion of Christ on the exterior and the Life of the Virgin when open. Here, the Dormition or "falling asleep" of the Virgin at the end of her life is paired with an image of her son carrying the cross on the way to his execution. The peacefulness of the mother’s death, surrounded by reverent apostles, contrasts with Christ’s suffering and the mockery of his tormenters.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Dormition of the Virgin; (reverse) Christ Carrying the Cross

- Artist: Hans Schäufelein (German, Nuremberg ca. 1480–ca. 1540 Nördlingen)

- Artist: and Attributed to the Master of Engerda (German, active ca. 1510–20)

- Date: ca. 1510

- Medium: Oil and gold on fir

- Dimensions: 55 x 53 1/8 in. (139.7 x 134.9 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Karen and Mo Zukerman, Kowitz Family Foundation, Anonymous, and Hester Diamond Gifts, 2011

- Object Number: 2011.485a, b

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

5225. The Dormition of the Virgin; (reverse) Christ Carrying the Cross, Part 1

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.