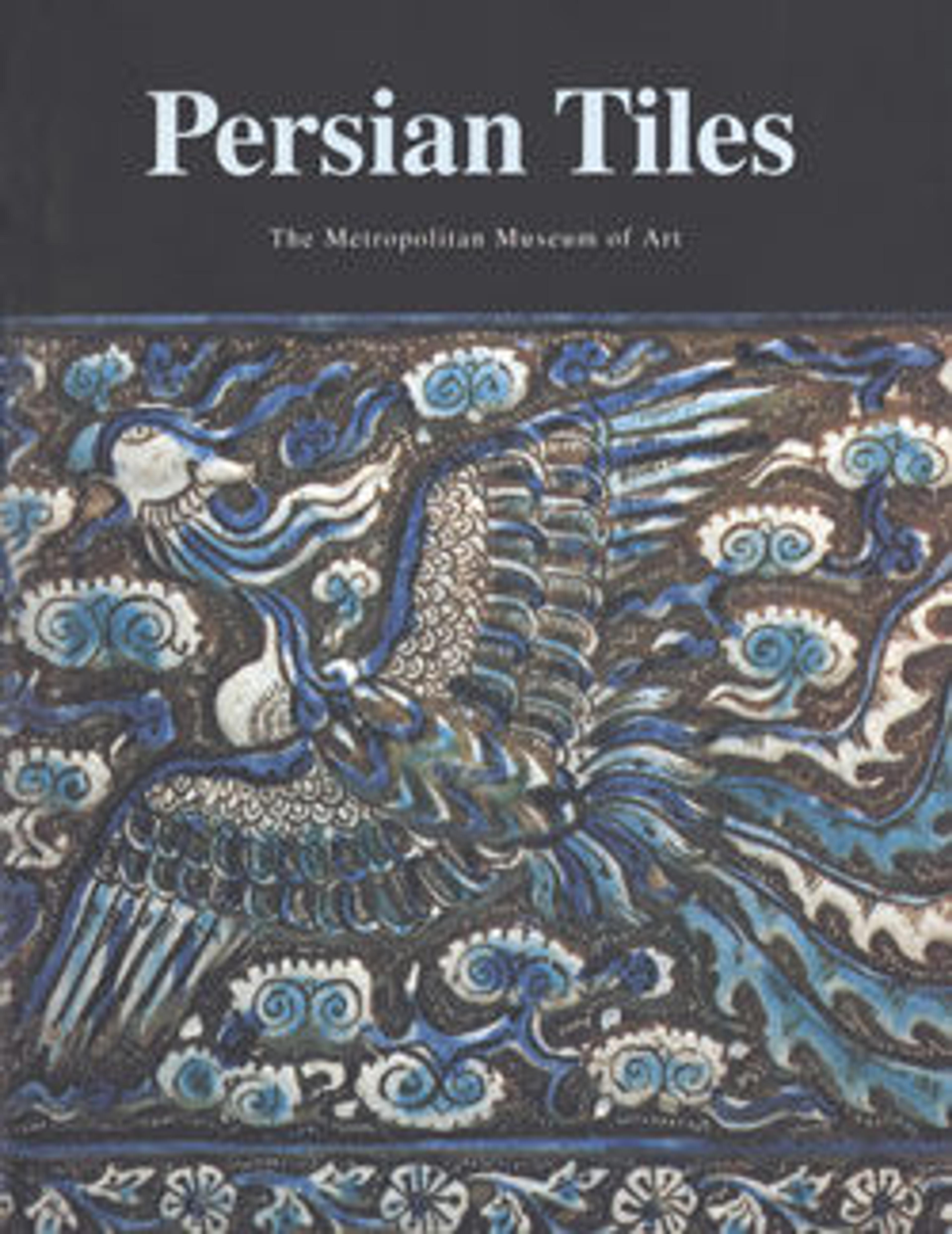

Tile with an Image of a Prince on Horseback

Mainly produced in Tehran, the Qajar capital, continuous friezes of rectangular underglaze-painted tiles, such as this example, were common in nineteenth-century architecture. Here, a young man on horseback is depicted with his hand extended toward Huma, the fabulous bird, the embodiment of health and strength, hovering over his head. Only royalty fell under the shadow of Huma, suggesting that the horseman depicted here is a prince.

Artwork Details

- Title: Tile with an Image of a Prince on Horseback

- Date: second half 19th century

- Geography: Made in Iran

- Medium: Stonepaste; molded, polychrome painted under transparent glaze

- Dimensions: H. 13 1/2 in. (34.3 cm)

W. 10 3/4 in. (27.3 cm)

D.

Wt. - Classification: Ceramics-Tiles

- Credit Line: Bequest of George White Thorne, 1883

- Object Number: 83.1.67

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.