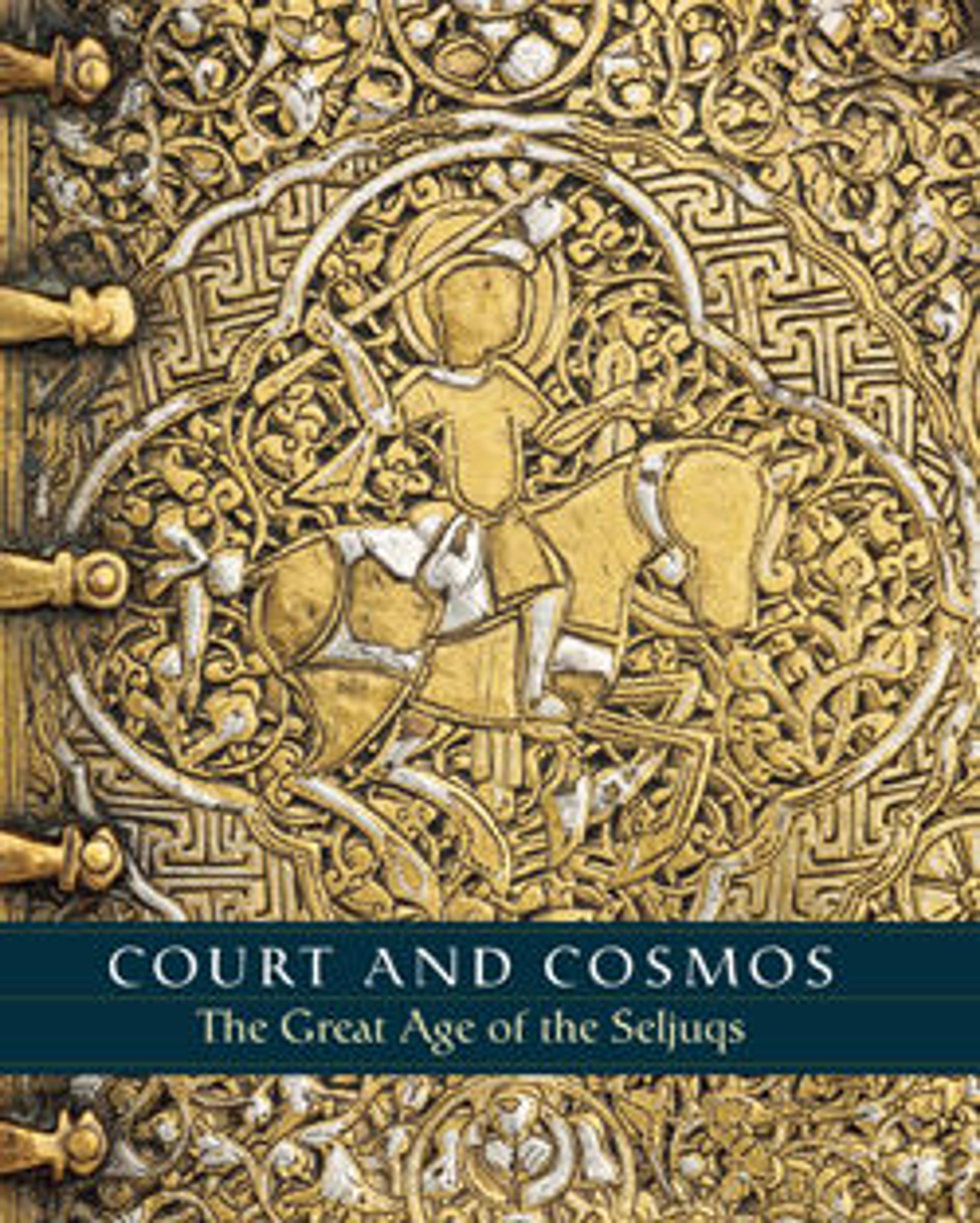

Candlestick with Enthronement Scene

This sophisticated candlestick illustrates various scenes celebrating the sovereign’s power over both earth and cosmos: images of the planets appear alongside scenes of him slaying a lion and enjoying a royal feast. His authority becomes most evident in the enthronement scene. Here, a bearded figure bends to kiss the ruler’s right hand, alluding to the obligation of kissing the sovereign’s hand or the floor before him. This courtly display of obeisance demonstrated the ruler’s supremacy and the loyalty of his subjects.

Artwork Details

- Title: Candlestick with Enthronement Scene

- Date: second quarter 13th century

- Geography: Attributed to Jazira, probably Mosul. Country of Origin Iraq

- Medium: Brass; engraved, incised, inlaid with silver

- Dimensions: H. 9 9/16 in. (24.4 cm)

Diam. 14 1/2 in. (36.8 cm) - Classification: Metal

- Credit Line: Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891

- Object Number: 91.1.563

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

Audio

605. Candlestick with Enthronement Scene

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.