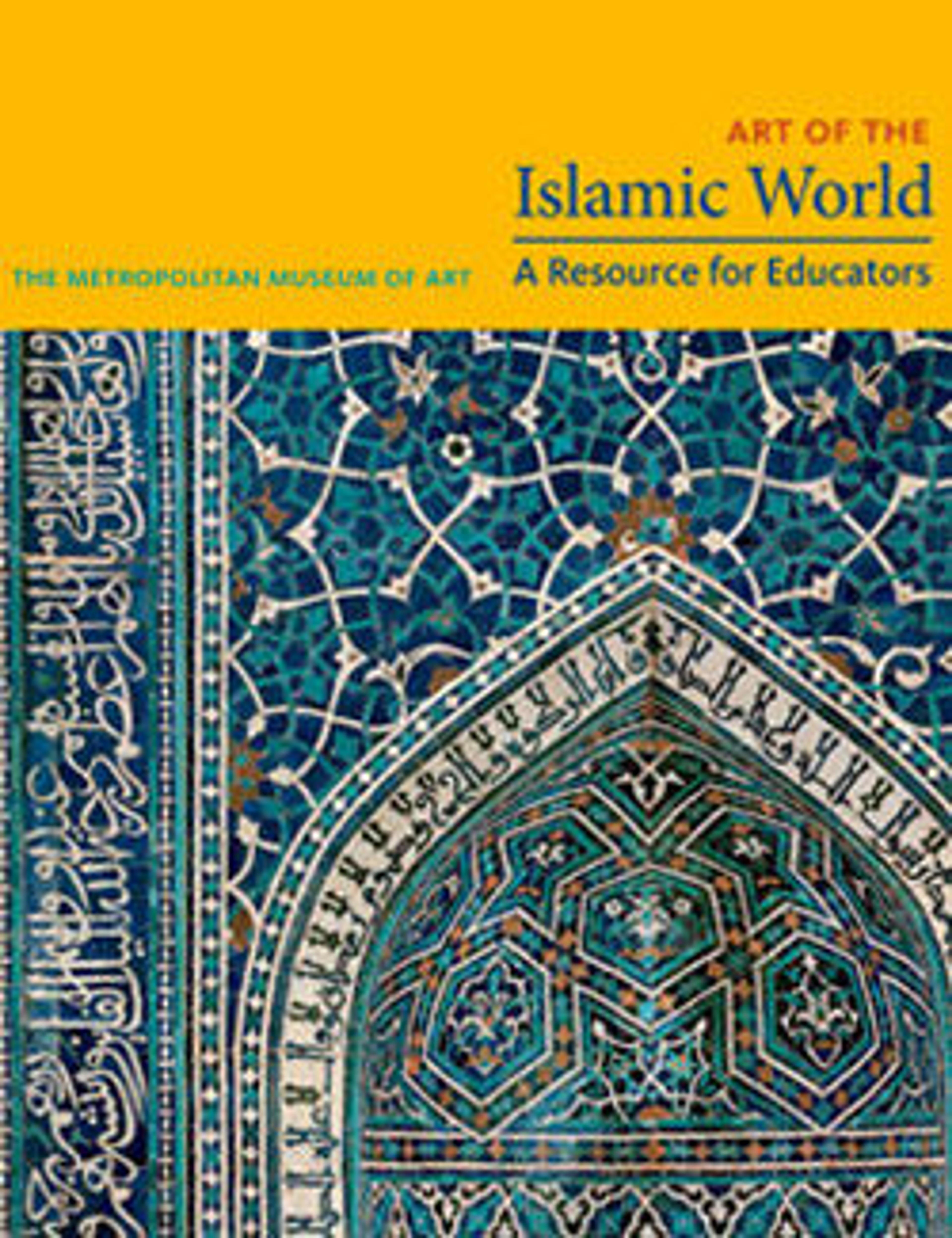

Tile with Image of Phoenix

Artwork Details

- Title: Tile with Image of Phoenix

- Date: late 13th century

- Geography: From Iran, probably Takht-i Sulaymän

- Medium: Stonepaste; modeled, underglaze painted in blue and turquoise, luster-painted on opaque white ground

- Dimensions: H. 14 3/4 in. (37.5 cm)

W. 14 1/4 inl (36.2 cm) - Classification: Ceramics-Tiles

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1912

- Object Number: 12.49.4

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

Audio

6709. Tile with Image of Phoenix, Part 1

DENISE-MARIE TEECE: My name is Denise-Marie Teece. And I'm a Research Associate in the Department of Islamic Art. And I'm here with my colleague Maryam Ekhtia. And we're talking today about this beautiful phoenix tile.

MARYAM EKHTIAR: This phoenix tile is a wonderful piece from an Ilkhanid Palace,14th Century. It's got a molded design… And it shows this mythical bird, soaring to the skies. It's got very lively feathers and long plumage.

DENISE-MARIE TEECE: So this tile is really a striking example of the adoption of Chinese imagery by Persian artists in the 14th Century. And how this happened was that, during the 14th Century, in the Ilkhanid period, there was a vast trading network that opened up between China and Iran.

MARYAM EKHTIAR: The phoenix is actually a Chinese motif. However, the Persian potters and painters take it and transform it into a bird that is thoroughly Persian. …It's a bigger-than-life bird living in the mountains. And in the Shahnameh, the Book of Kings, the phoenix figures very prominently.

DENISE-MARIE TEECE: From excavations, we know that these kinds of tiles were used in the Ilkhanid Palace, the Summer Palace known as Takht-i Sulayman. So within these palaces, tiles like this with the phoenix would have alternated with similar tiles, but with dragon motifs. So both of these are being taken from Chinese iconography.

NARRATOR: To hear about Chinese and Islamic connections along The Silk Road, press PLAY.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.