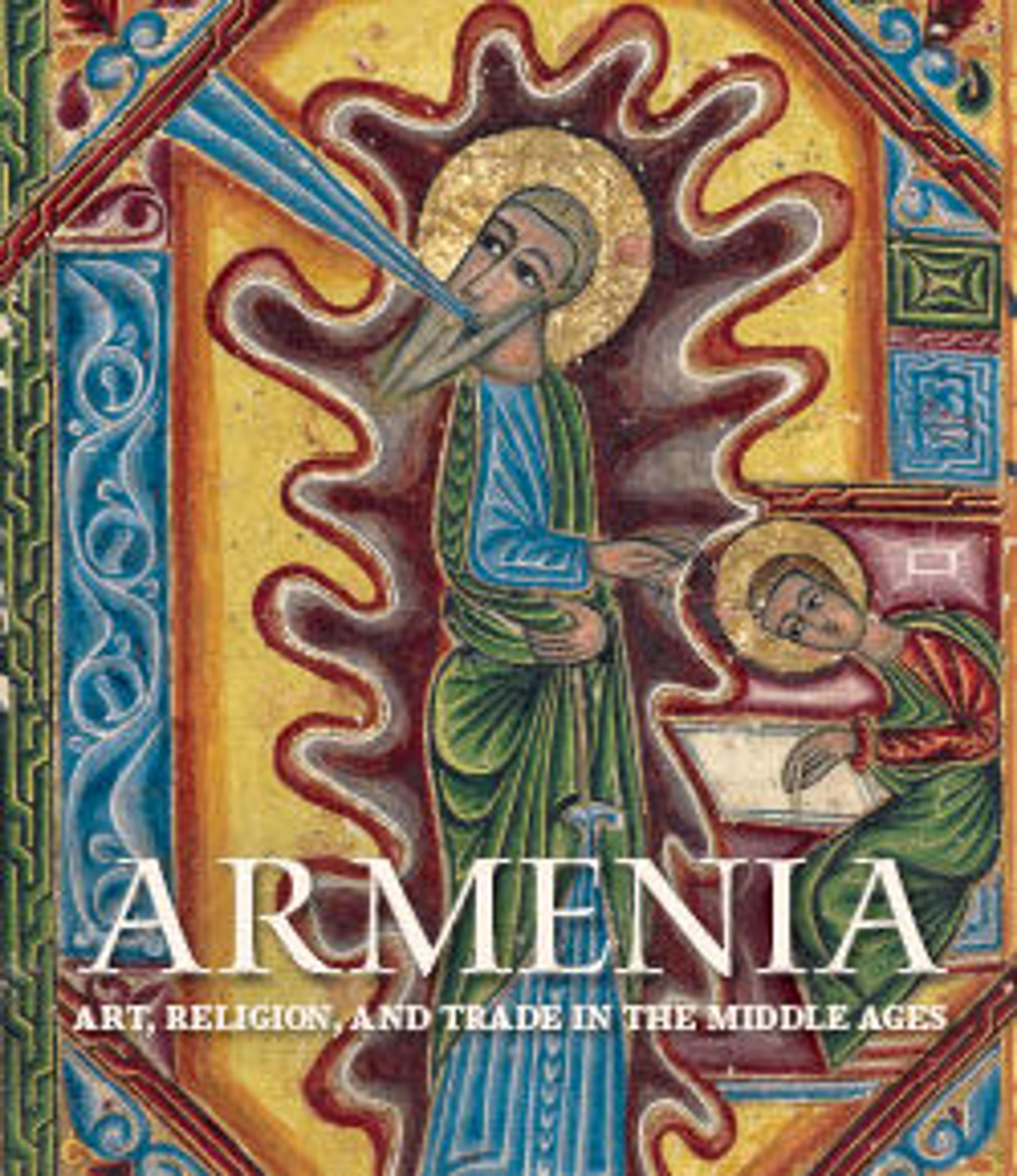

Cope

Armenian merchants played an important role in facilitating trade in and outside Iran, so when the Safavid ruler Shah 'Abba' (r. 1587–1629) planned to revitalize Iran's economy, he resettled a community of Armenians from the city of Julfa to his new capital, Isfahan. From there, the Armenians helped Iran's famous silk reach markets around the world. This cope probably comes from an Armenian church in Isfahan, as suggested by the presence of Armenian bishop-saints and Armenian inscriptions on the orphrey attached to its long straight edge. The cope was pieced together from robes (the seams are still visible) of a type of costly, popular seventeenth-century Persian velvet.

Artwork Details

- Title: Cope

- Date: first half 17th century (velvet)

- Geography: Attributed to Iran

- Medium: Silk, cotton, metal wrapped thread; cut and voided velvet, brocaded, embroidered, with engraved metal fittings

- Dimensions: Textile: Max. L. 44 1/2 in. (113 cm)

Max. W. 103 in. (261.6 cm)

D. 1/4 in. (0.6 cm) - Classification: Textiles

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1914

- Object Number: 14.67

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.