Tombstone of Abu Sa'd ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Hasan Karwaih

Artwork Details

- Title: Tombstone of Abu Sa'd ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Hasan Karwaih

- Maker: Ahmad ibn Muhammad Astak (Iranian)

- Date: dated 545 AH/1150 CE

- Geography: Attributed to Iran, Yazd

- Medium: Marble; carved, painted

- Dimensions: H. 22 1/4 in. (56.5 cm)

W. 14 5/8 in. (37.1 cm)

D. 2 7/8 in. (7.3 cm)

Wt. 64lb. (29kg) - Classification: Stone

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1933

- Object Number: 33.118

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

Audio

6684. Tombstone of Abu Sa'd ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Hasan, Part 1

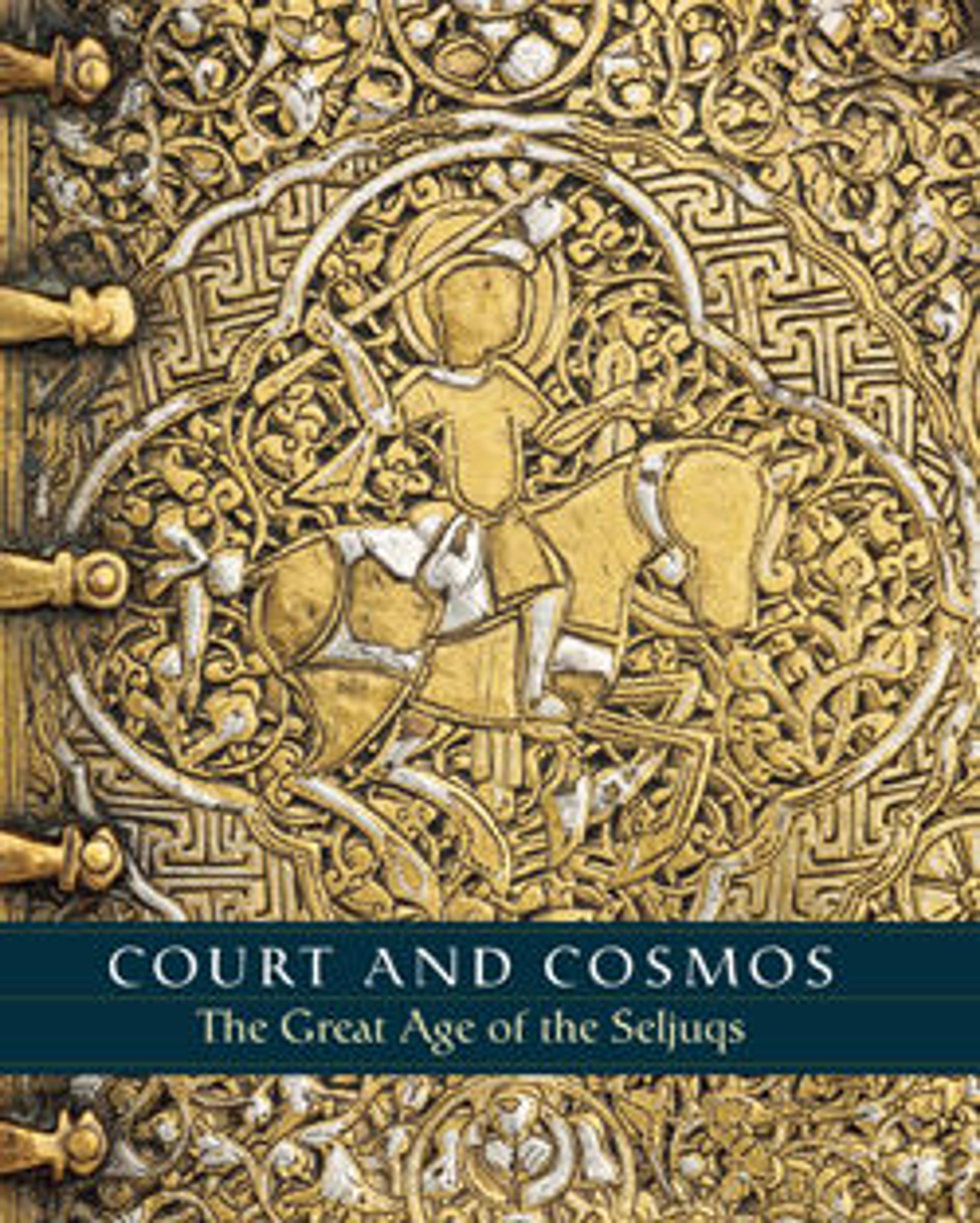

NARRATOR: In the center of this carving is a shape which refers to a prayer niche. It has three different styles of script. The inscriptions around the outermost edge tell us that this came from Iran.

DENIZ BEYAZIT: Hi, I'm Deniz Barzit. I'm one of the curators in the Islamic Art Department. We are standing in front of a tombstone. Let's have a closer look on the content of the inscriptions, which is interesting. …We have a surat from the Qur’an going around on the outside. Then we have here in the upper part just above the niche, one line, which is the Shahada, the profession of faith, that there is only one God and no other god in the world and Mohammed is his prophet. And then we have, also, very interesting, at the bottom, a line where it is said, "This is the work of [Ahmed], son of Mohammed [Ashtak]." So we have the name of the artist and if we go further into the details, we see in the center of the niche, we have one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight lines where it is clearly said that "This is the grave of Abu S’ad, son of Mohammed, son of Ahmad son of [unintelligible], and he died in the month of Muharram of the year 545," which in our calendar is 1150.

NARRATOR: The shape of the central prayer niche refers to the prayer niche of a mosque, known as the mihrab. As you explore, you can hear some thoughts about how many of the objects in these galleries refer to ritual practices in the mosque. Press PLAY.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.