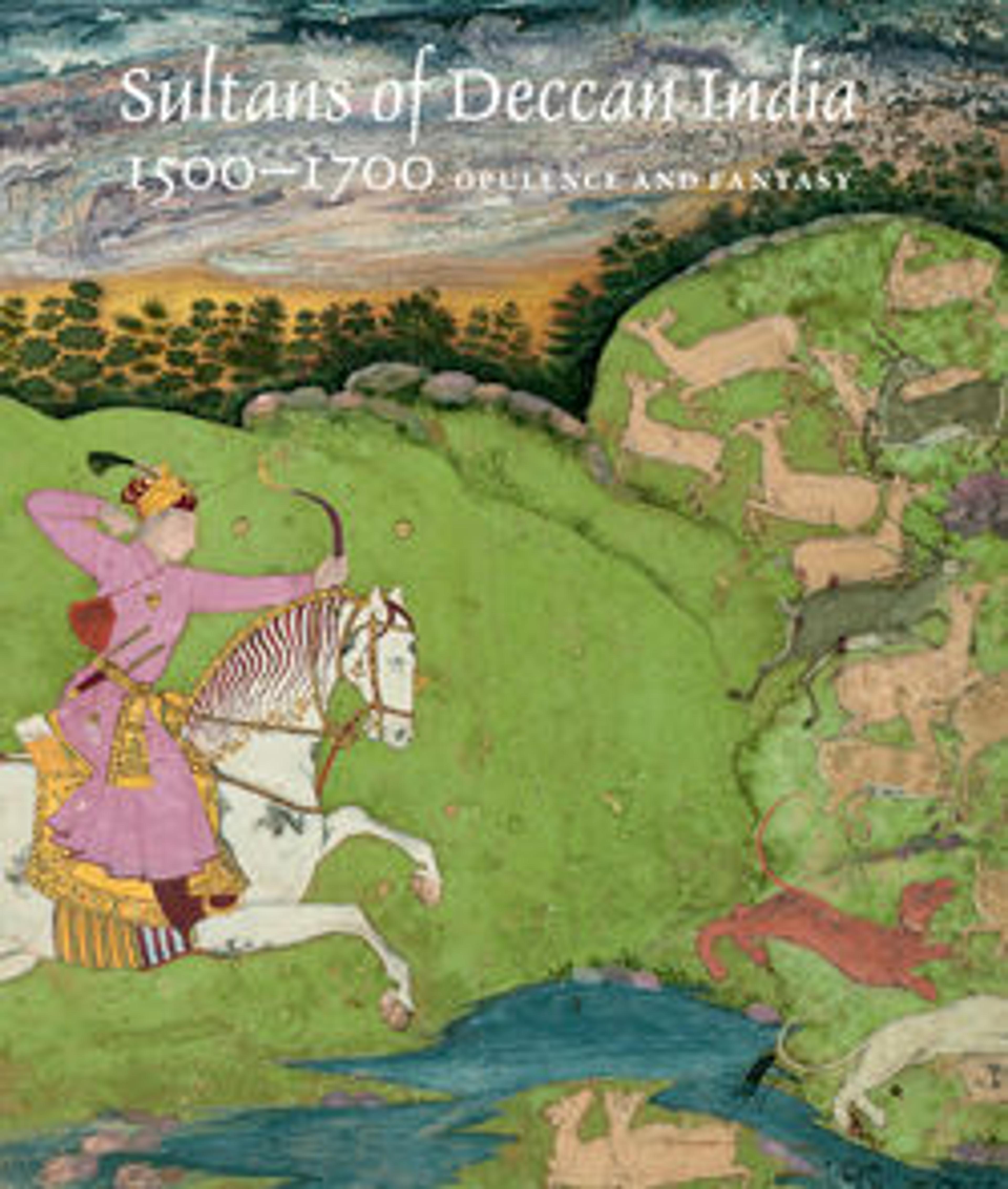

The House of Bijapur

This image from Bijapur made for the last of its rulers, Sikandar, shown here as a young boy soon before the fall of the kingdom to Mughal conquerors in 1686, brings together all nine ‘Adil Shahi sultans in a dynastic assembly likely inspired by Mughal paintings illustrating the same idea. Distant views of water hint at Bijapur’s former vastness, which, at its greatest extent, stretched to include Goa on the Arabian Sea. The key of legitimacy is being handed over by Isma’il, founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran (here erroneously identified as Shah ‘Abbas in a later inscription), to Yusuf, founder of the Bijapur dynasty, symbolizing the unwavering allegiance of the ‘Adil Shahi family to the Shi’ite creed. During its golden period under the free-thinking Ibrahim II (1579–1626, shown third from right), however, Bijapur witnessed an open embrace of Hinduism and Sufism and the formalization in 1583 of Sunnism as the state religion, which lasted until the end of his tenure.

Artwork Details

- Title: The House of Bijapur

- Artist: Painting by Kamal Muhammad (active 1680s)

- Artist: Painting by Chand Muhammad (Indian, active 1680s)

- Date: ca. 1680

- Geography: Made in India, Deccan, Bijapur

- Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper

- Dimensions: Page: H. 16 1/4 in. (41.3 cm)

W. 12 13/16 in. (32.5cm)

Mat: H. 22 in. (55.9 cm)

W. 16 in. (40.6 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Purchase, Gifts in memory of Richard Ettinghausen; Schimmel Foundation Inc., Ehsan Yarshater, Karekin Beshir Ltd., Margaret Mushekian, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Ablat and Mr. and Mrs. Jerome A. Straka Gifts; The Friends of the Islamic Department Fund; Gifts of Mrs. A. Lincoln Scott and George Blumenthal, Bequests of Florence L. Goldmark, Charles R. Gerth and Millie Bruhl Frederick, and funds from various donors, by exchange; Louis E. and Theresa S. Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art and Rogers Fund, 1982

- Object Number: 1982.213

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

Audio

6733. The House of Bijapur, Part 1

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.