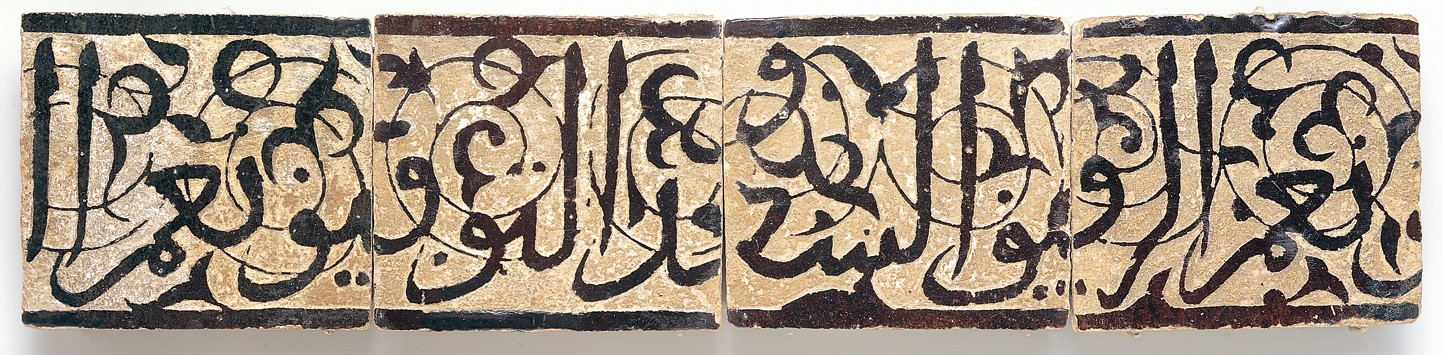

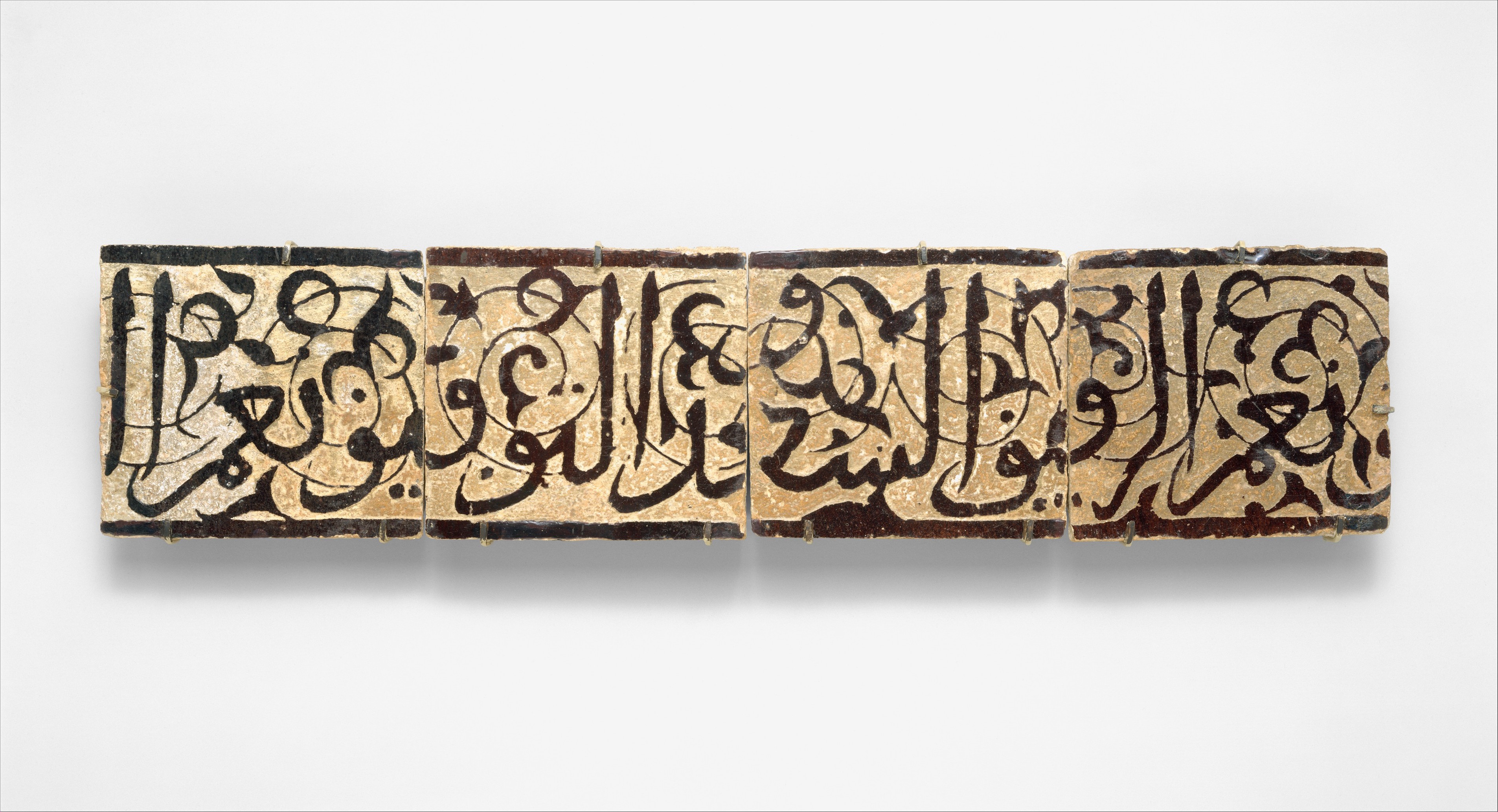

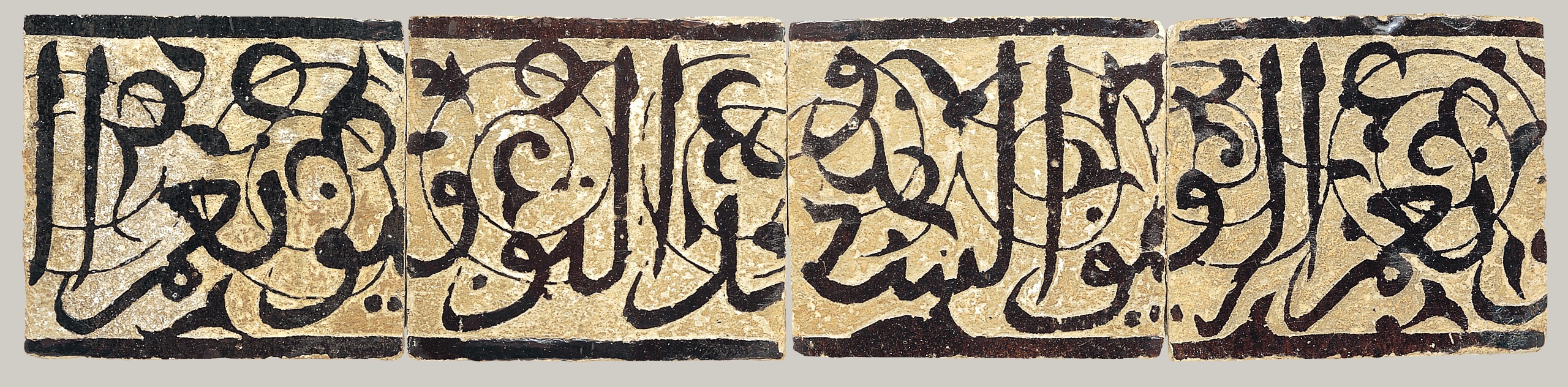

Panel of Four Calligraphic Tiles

Not on view

Epigraphic friezes executed in ceramic tile were integral to the decorative program of interiors in both Morocco and Spain. They were situated near eye-level, between a dado of tile mosaic and upper-wall decoration of carved stucco. These tiles were first entirely coated in purplish-black glaze, which was carved away leaving behind the calligraphy on a background of foliate scrolls.

#6718. Panel of Four Calligraphic Tiles

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.