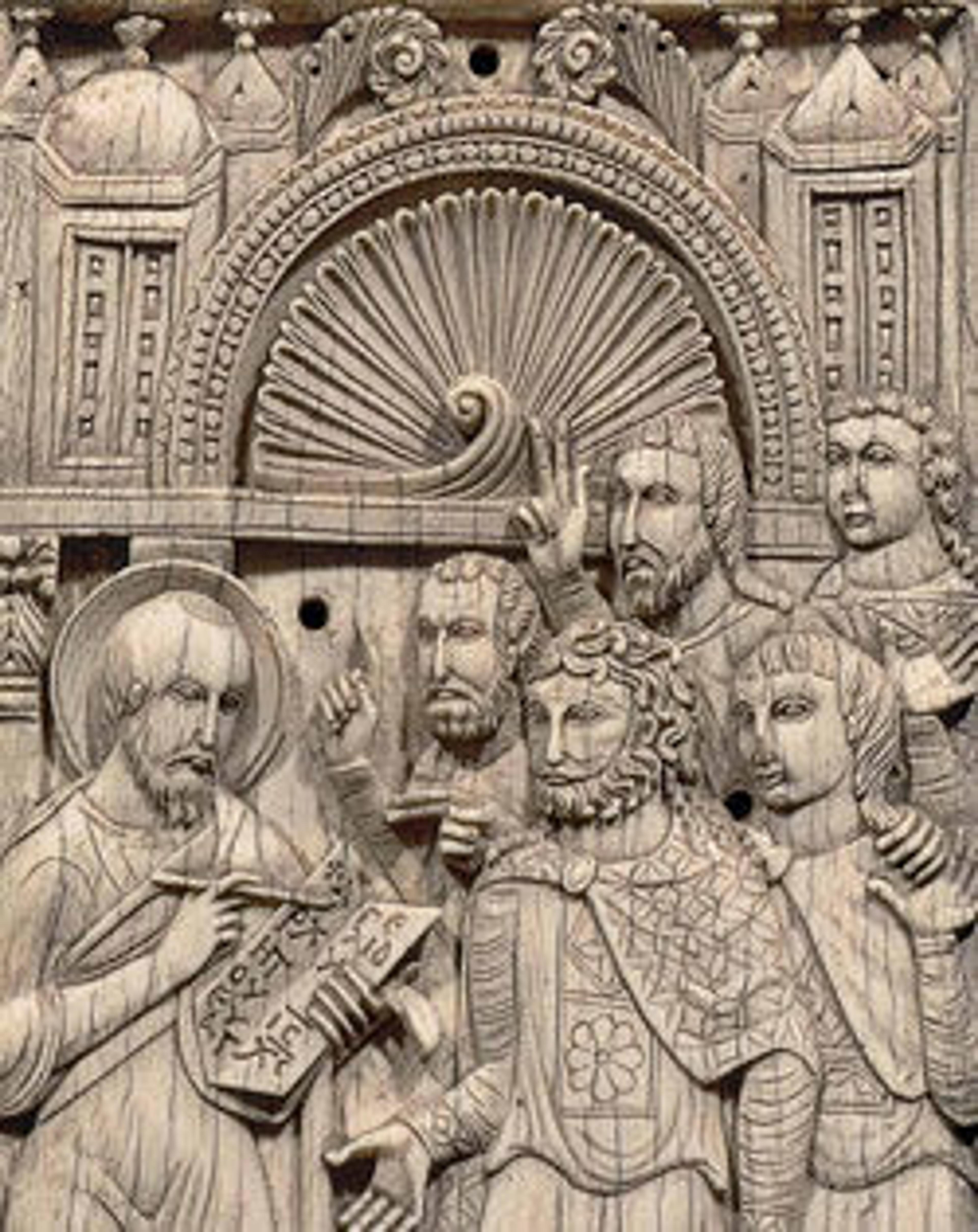

Fragment of a Frieze with the Miracle of Loaves and Fishes

On this heavily damaged stone, Christ sits enthroned under an arch, extending his right hand toward twelve baskets. Saint Mark the Evangelist (6:33–44) wrote that from a meager five loaves and two fish, Christ was able to feed a crowd of five thousand people—with twelve baskets of food left over, as here. In this depiction, angels stand to Christ’s left and right; beyond them, apostles or saints carry books in their left hand and gesture with their right as if speaking or preaching.

Artwork Details

- Title: Fragment of a Frieze with the Miracle of Loaves and Fishes

- Date: 6th–7th century

- Geography: Said to be from Egypt, Bawit

- Medium: Limestone; carved

- Dimensions: H. 9 5/8 in. (24.5 cm)

W. 39 38 in. (100 cm)

D. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm)

W. 112 lb. (50.8 kg) - Classification: Sculpture

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1910

- Object Number: 10.176.21

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.