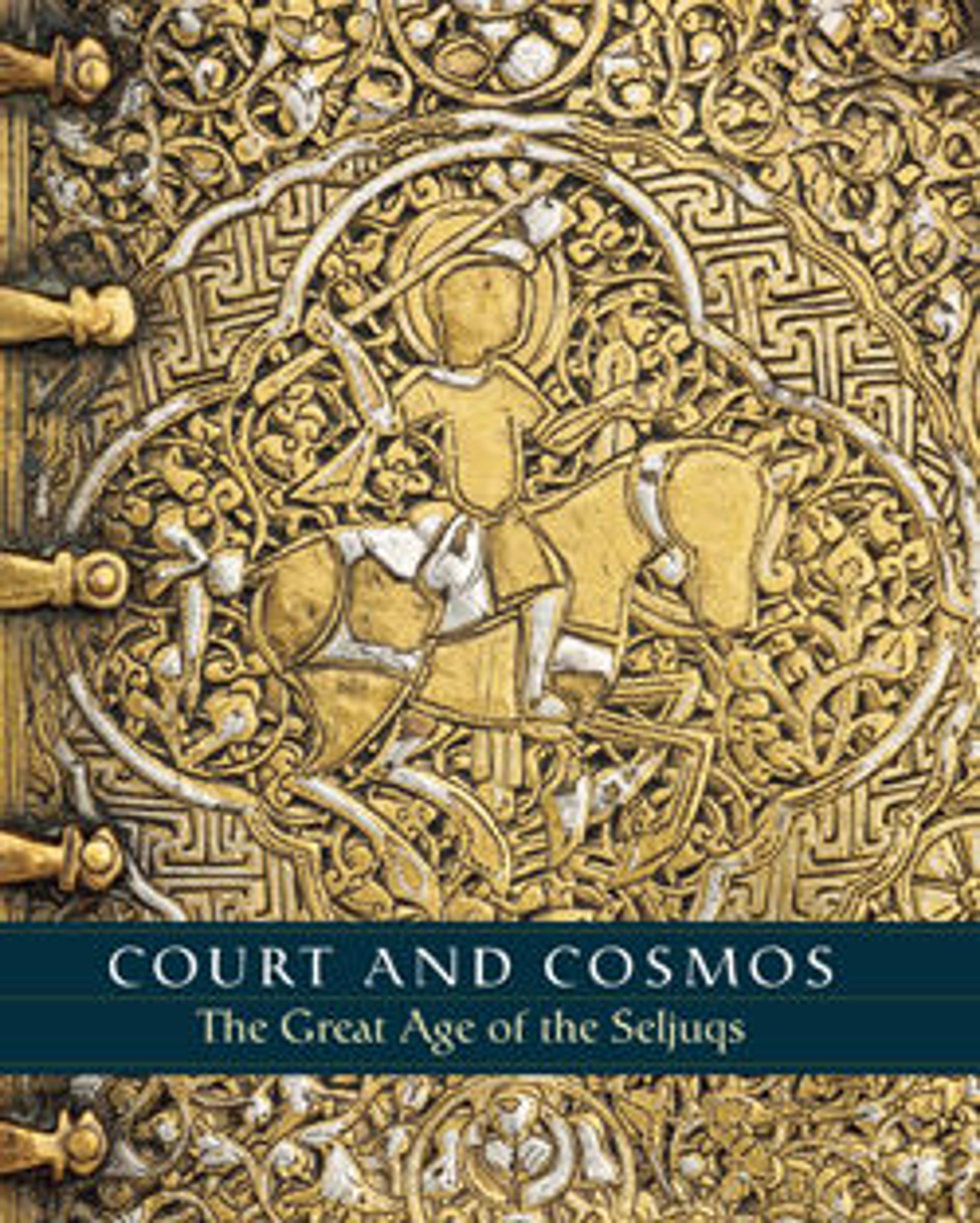

Gravestone of Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, died Shawwal 532 A.H. [June/July 1138 A.D.]

The inscription states that it is the tombstone of “the Shaykh, the martyr Jamal al-Qura' Muhammad b. Abi Bakr b. Amin al-Muqri' Khwajakak.” “Shaykh” identifies the deceased as a scholar, Sufi, or social leader, while “martyr” suggests that his death did not occur naturally. The son of a muqri' or Qur'an reciter, Jamal is characterized as “al-Qura',” an ascetic. “Khwajakak” is related to the Persian word for merchant, possibly his occupation.

Artwork Details

- Title:Gravestone of Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, died Shawwal 532 A.H. [June/July 1138 A.D.]

- Date:dated 532 AH/1138 CE

- Geography:Found Iran, Nishapur

- Medium:Steatite; carved

- Dimensions:H. 16 in. (40.6 cm)

W. 13 3/4 in. (34.9 cm)

D. 3/4 in. (1.9 cm) - Classification:Stone

- Credit Line:Rogers Fund, 1948

- Object Number:48.101.3

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.