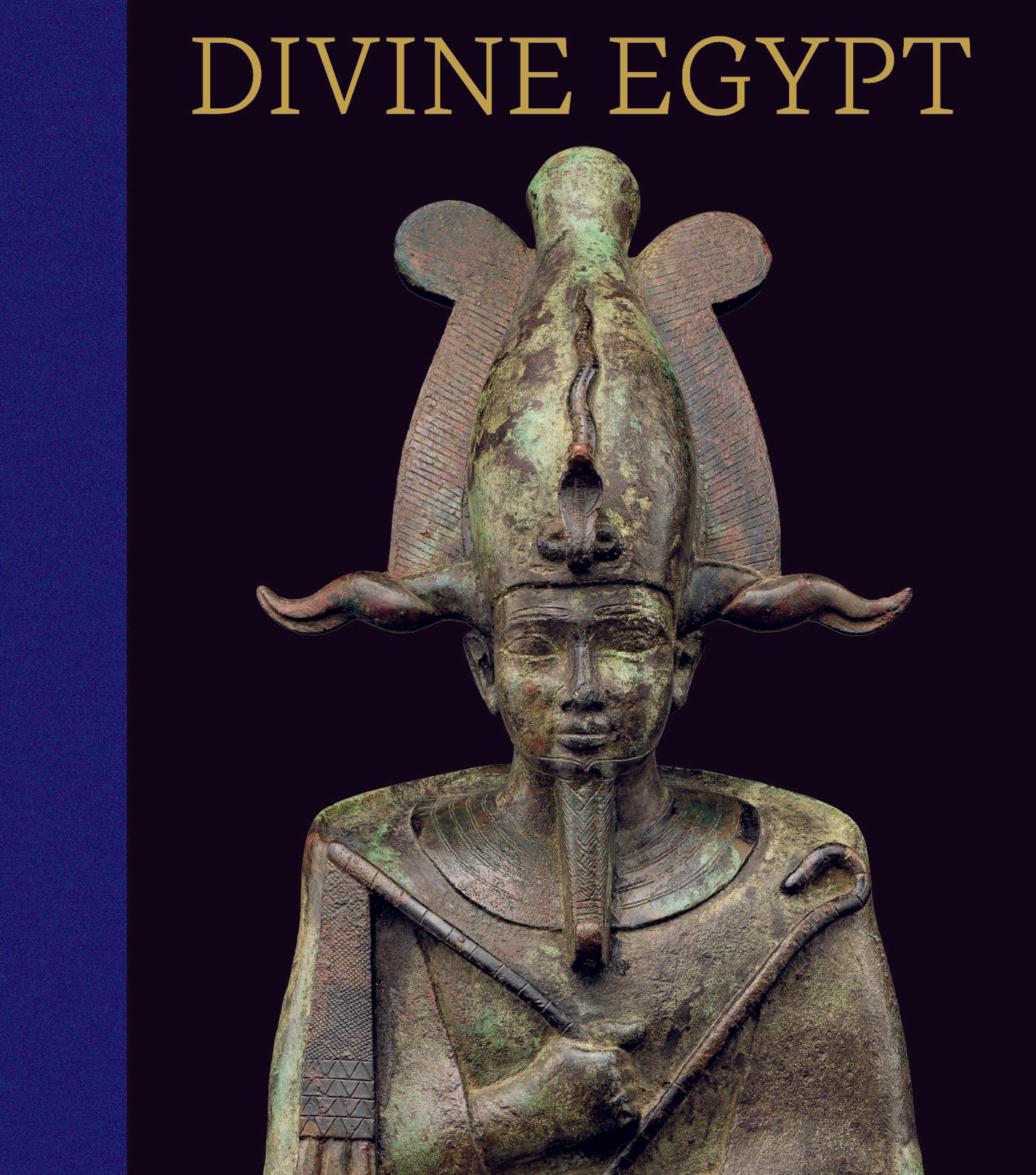

Statuette of an ancestral king

It is not easy to explain the presence among the animal-headed divinities of the human-headed figure wearing—as seen here—the regalia of a pharaoh. Some scholars interpret the figure as the representation of an actual king. Others understand it as a mythical being that introduces royal aspects into the otherworldly ritual. Whatever its exact meaning, this masterpiece of wood carving was certainly part of a temple's equipment. Its ritual character was further emphasized by a covering of lead sheet, now vanished.

Artwork Details

- Title: Statuette of an ancestral king

- Period: Late Period–Early Ptolemaic Period

- Dynasty: Dynasty 30 or later

- Date: 390–246 BCE

- Geography: From Egypt

- Medium: Wood, formerly clad with lead sheet

- Dimensions: H. 20.8 × W. 14.5 × D. 11 cm (8 3/16 × 5 11/16 × 4 5/16 in.); H. (with tang): 23.3 cm (9 3/16 in.)

- Credit Line: Purchase, Anne and John V. Hansen Egyptian Purchase Fund, and Magda Saleh and Jack Josephson Gift, 2003

- Object Number: 2003.154

- Curatorial Department: Egyptian Art

Audio

3271. Ritual Figure, Part 1

At this wonderfully animated figure, we have a conversation between Philippe de Montebello, Director Emeritus of the Metropolitan Museum, and Dorothea Arnold, Head of the Egyptian Department. They remember when the statue first arrived at the Met.

PHILLIPE DE MONTEBELLO: What puzzled me at the time was your saying to me, that actually this piece, whose surface¬– the wonderful polish of the wood I so admired – was actually the underside, that it had originally covered with lead. Is that correct?

DOROTHEA ARNOLD: That is correct. And that’s of course what also preserved the woodwork in such a pristine condition. This is a piece from an Egyptian temple. And, this is a world of a lot of magical potency. So to increase that, they often sheathed pieces either in gold, silver, or in this case, lead, which had a special magical meaning.

PHILLIPE DE MONTEBELLO: The thinness of the cloth of the skirt as it stretches between the uplifted knee and the other – it’s just a wonderful rendering. And the hollow below the knee, the wonderful curvature of the leg, it’s magical.

DOROTHEA ARNOLD: Indeed, it’s like a dancer really….

PHILLIPE DE MONTEBELLO: … This is a reaction to something seen, surely.

DOROTHEA ARNOLD: I would say so too. And it does indeed speak to everybody. You don’t have to know very much about ancient Egypt I think.

PHILLIPE DE MONTEBELLO: Although, ironically, I wonder if our modern sensibility doesn’t prefer the piece in its current state, than had it been covered with lead.

DOROTHEA ARNOLD: I think yes there’s something about that, and in its life now in the museum this is the way it lives with us.

NARRATOR: The figure is actually doing a specific ritual dance, called “henu.” To hear about it, press PLAY.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.