Installation photo of the "Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá" gallery in Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 28, 2018

Visitors to Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas encounter an immersive gallery (designed by Dan Kershaw) containing works of art found at a single site: the Sacred Cenote of Chichén Itzá. This sinkhole, formed from a collapsed cave in the limestone bedrock, became one of the greatest repositories of offerings in the ancient Americas. The extraordinary assemblage contains a wealth of information about indigenous concepts of value among the Maya, the foreign presence or influence at Chichén Itzá, and an unparalleled look into rituals of sacrifice.

Named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988, Chichén Itzá is one of the most visited destinations in Mexico. In fact, the city, with its iconic pyramids and temples covered in elaborate sculptural programs, has been a popular destination since at least the first millennium A.D. Over the course of centuries, Maya peoples from all over the northern Yucatan Peninsula visited Chichén Itzá, many of them on a pilgrimage to the Sacred Cenote (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The Sacred Cenote. Photo by Kim N. Richter

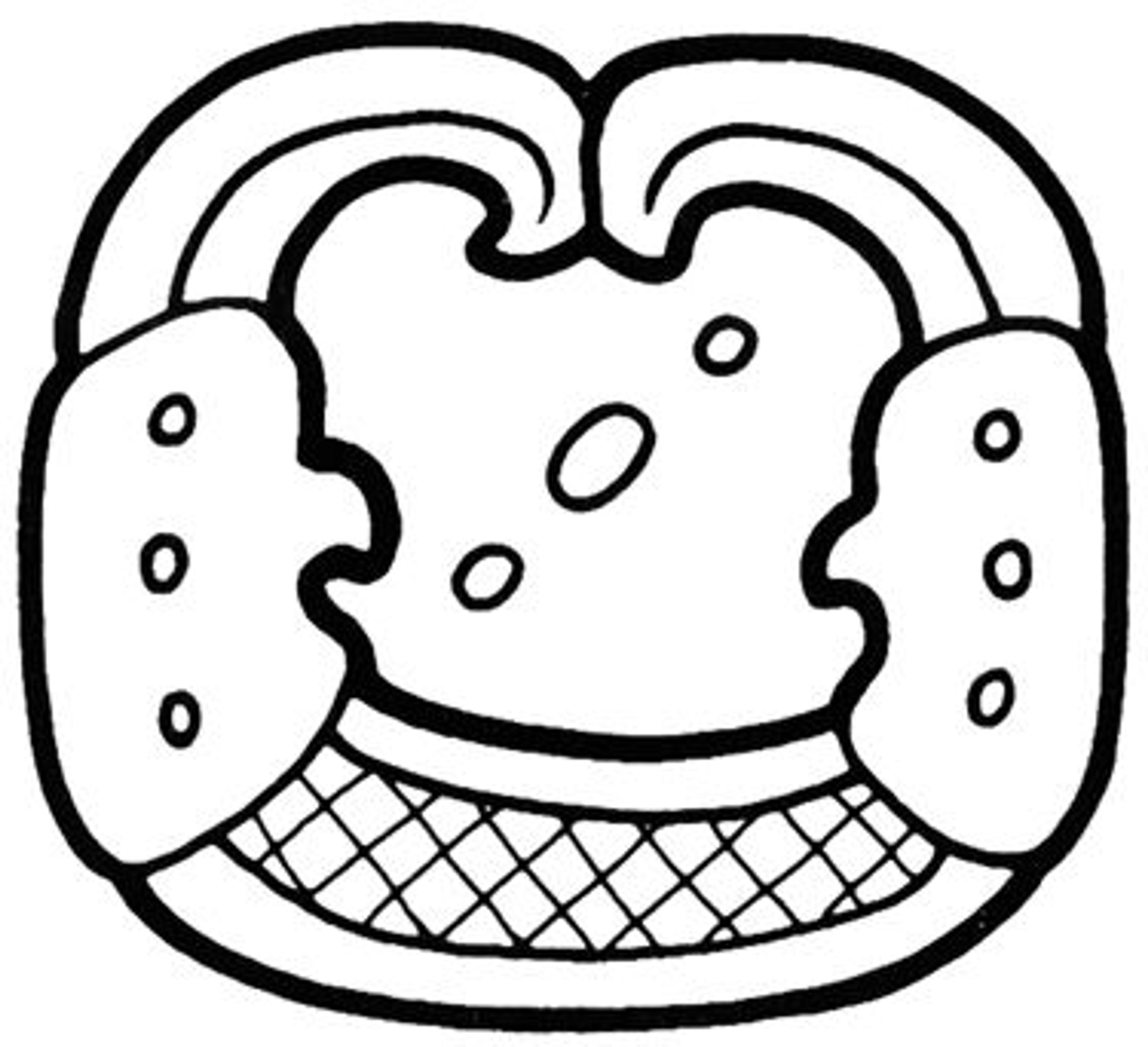

Cenotes were central in Maya cosmology as the liminal spaces that served as vital portals between the earthly realm and the watery underworld. Through this opening, the deceased passed, and from this opening, humans and deities were reborn. Artists and scribes depicted cenotes in Maya art as the gaping, bony jaws of a great centipede (fig. 2). On the other side of the centipede's jaws, dark characters of the underworld lurked.

Fig. 2. Drawing of the Maya hieroglyphic sign for "cenote." From Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting. Drawing by Marc Zender

People probably offered a variety of objects for a variety of motivations. The tossing of precious things into the cenote reaffirmed the resident's or pilgrim's dedication to the natural cycles that created life-giving rains so vital to sustaining maize cultivation and the lives of their ancestors. Archaeological investigations in the twentieth century at the Sacred Cenote of Chichén Itzá—including the controversial dredging project directed by Edward H. Thompson from 1904 to 1910, and later projects led by Mexican archaeologists under the aegis of the National Institute of Anthropology and History—recovered human remains and an impressive array of luxury goods, the result of repeated depositions by locals or visitors from faraway places.

Jade was the most precious material to the ancient Maya, and hundreds of jade objects were thrown into the Sacred Cenote. Plaques and pectorals were ritually burned and fractured; some of these were possibly heated up to shatter when they hit the cold water. A number of plaques in non-local styles attest to the wide-ranging trade networks in place near the end of the first millennium A.D.

A plaque on view in Golden Kingdoms, likely sculpted by artists from the Pacific coast of Guatemala, depicts a richly attired figure holding a small cacao tree and standing on the back of a monumental crab (fig. 3, left). To the right of the ruler is a column of circular hieroglyphs, which are also unique to Pacific Guatemala. In that region, peoples grew cacao, which was highly valued as a tribute good in ancient Mesoamerica and is the main component used to create chocolate today. Other artists carved jade plaques and beads in the famed Maya-Toltec style, perhaps at the site itself (fig. 3, right). They were subsequently removed from economic and ritual circulation, and sacrificed to the cenote.

Fig. 3. Left: Plaque, A.D. 700–1100. Mexico, Yucatan, Chichén Itzá, Sacred Cenote. Maya. Jadeite, 13.7 x 11.3 x 0.6 cm (5 3/8 x 4 7/16 x 1/4 in.). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (10-71-20/C7410). Right: Plaque, A.D. 700–900. Mexico, Yucatan, Chichén Itzá, Sacred Cenote. Maya. Jadeite, 9.3 x12.8 x 0.6 cm (3 11/16 x 5 1/16 x 1/4 in.). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (10-71-20/C6666). Photos © President and Fellows of Harvard College

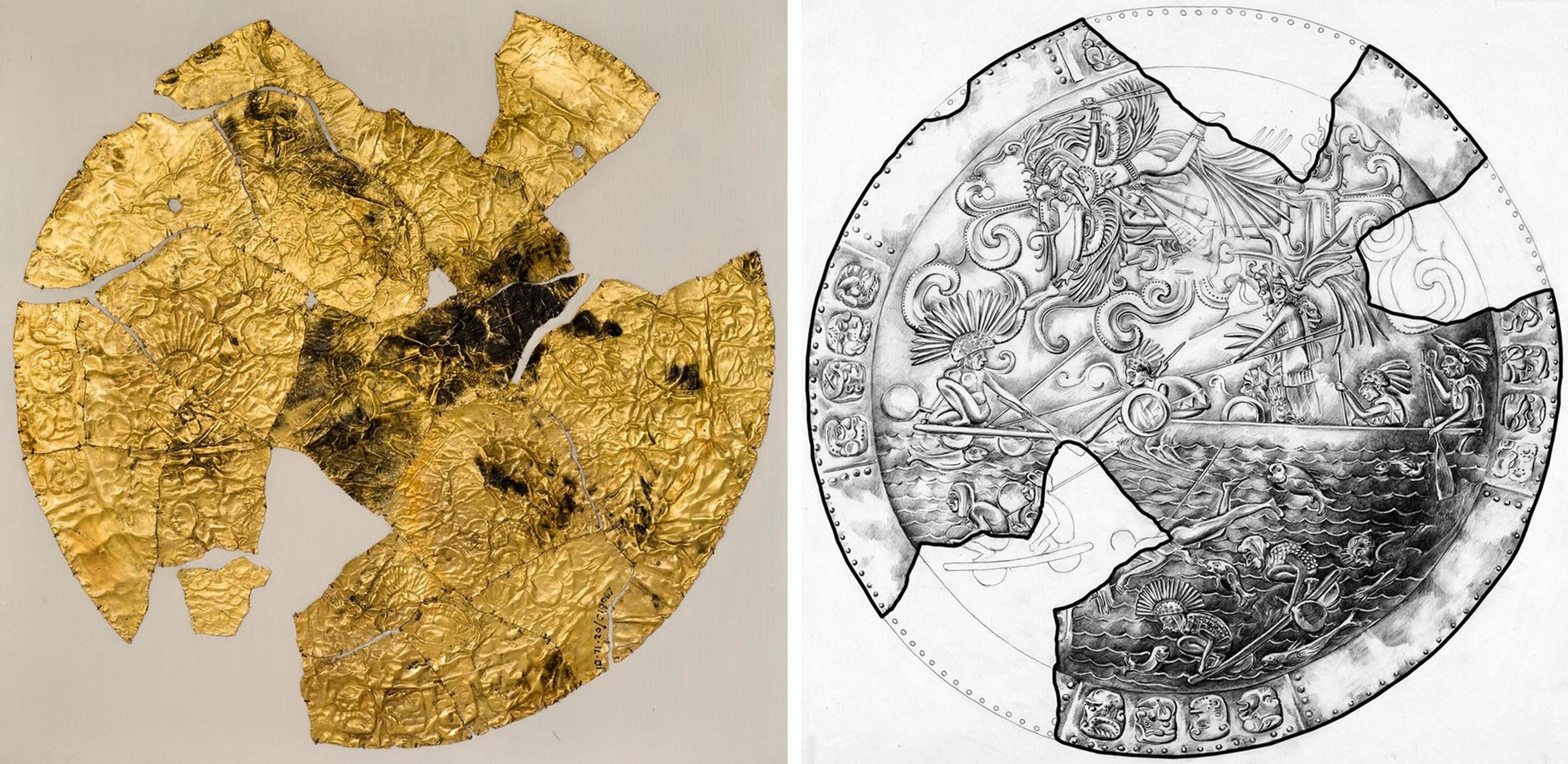

Gold and copper objects are scarce in Maya tombs and caches, but the Sacred Cenote was full of metal. The sample of metal objects deposited directly into the cenote includes figures, bells, and disks made in Costa Rica and Panama (fig. 4, left). Additionally, the Maya of Chichén Itzá traded for gold to transform; they began importing finished hammered gold disks or native gold in the form of nuggets. During the ninth century, the Maya began to rework the imported blank disks from southern Central America, hammering them to be paper-thin and chasing mythological scenes onto their surface (fig. 4, right).

Fig. 4. Left: Close-up view of a vitrine in Golden Kingdoms featuring an array of bells from Costa Rica or Panama deposited in the Sacred Cenote. Photo by author. Right: Disk H (detail), A.D. 800–900. Mexico, Yucatan, Chichén Itzá, Sacred Cenote. Maya. Gold; 22 x 21.5 x 0.1 cm (8 5/8 x 8 7/16 x 1/16 in.) Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (10-71-20/C10068). Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

One such disk—which was burned, punctured, and torn up before being offered into the cenote—shows a rare scene of a naval battle between people in a large canoe and others on three small rafts (fig. 5). There are five people in the canoe, all with feathered headdresses, four of which have speech scrolls extending from their lips, a graphic representation of shouts of commands. The standing individual in the center, distinguished by his large circular earflares, holds two spears in his left hand as he readies a third in his right to throw at the fleeing raft to the left of the scene. The raft already suffered two direct spear hits, but its navigator survives to address his attackers. The artist who transformed this disk into a narrative scene fused reality, including jumping fish from the choppy water, with the mythological, as seen in the winged deity floating above the battle, perhaps a martial force on the side of the attackers.

Fig. 5. Left: Disk G, A.D. 800–900. Mexico, Yucatan, Chichén Itzá, Sacred Cenote. Maya. Gold, 24 x 20 x 0.1 cm (9 7/16 x 7 7/8 x 1/16 in.). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (10-71-20/C10067). Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Right: Drawing of disk G's original appearance by Tatiana Proskouriakoff

Perhaps the most incredible things from the cenote are those that were lost to the ravages of time elsewhere in the Maya Lowlands: works of art made from wood, textile, and other organic materials. Entire offerings were preserved whole, such as ceramic bowls with large quantities of copal resin into which the Maya stuffed jade beads (fig. 6). These conglomerate offerings are a window into the material aspect of a ritual world of the Maya that is otherwise unknown.

Fig. 6. Tripod bowl containing copal and jadeite beads, A.D. 1300–1450. Mexico, Yucatan, Chichén Itzá, Sacred Cenote. Maya. Copal, ceramic, jadeite, 12 x 12 x 12 cm (4 3/4 x 4 3/4 x 4 3/4 in.). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University (07-7-20/C4561). Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Resources

Coggins, Clemency Chase, ed. Artifacts from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichén Itzá, Yucatan. In Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Harvard University 10, no. 3. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Finamore, Daniel, and Stephen D. Houston, eds. Fiery Pool: The Maya and the Mythic Sea. Salem, MA, and New Haven, CT: Peabody Essex Museum, 2010.

Lothrop, Samuel K. Metals from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichén Itzá, Yucatan. In Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Harvard University 10, no. 2. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, 84, 226–241. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Getty Research Institute, 2017.

Proskouriakoff, Tatiana. Jades from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichén Itzá, Yucatan. In Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology Harvard University 10, no. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974.

Wren, Linnea, Cynthia Kristan-Graham, Travis Nygard, and Kaylee Spencer, eds. Landscapes of the Itza: Archaeology and Art History at Chichén Itzá and Neighboring Sites. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2017.

Related Content

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 28, 2018.

See more digital content related to Golden Kingdoms, including a walkthrough of the recent exhibition in English and in Spanish.

Read more articles in this exhibition's blog series.

Purchase a copy of the exhibition catalogue in The Met Store.