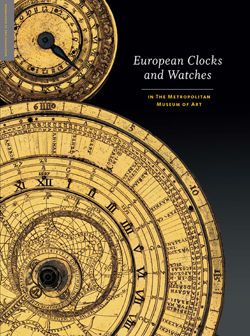

Watch in the form of a Lesser George

Movement by Nicholas Vallin Flemish

Made in the shape of the ensign of the order of the garter and named after Saint George, this watch was the epitome of prestigious watches when it was made. Founded in the fourteenth century by the English King Edward III (1312–1377), the Order of the Garter still exists. Its knights are installed according to custom in the magnificent fifteenth-century chapel of Saint George at Windsor Castle, and the ceremony is presided over by Queen Elizabeth II. In his history of the order, court historian Elias Ashmole (1617–1692) lists as part of its insignia the Greater George, an elaborate pendant image of Saint George fighting a dragon, which is worn on a collar as part of full ceremonial dress; and the Lesser George, a simpler pendant that the knights were obliged to wear in daily dress. Ashmole describes the Lesser George as being

for the most part made of pure Gold, curiously wrought by the hand of the Goldsmith, but we have seen divers of them exquisitely cut in Onix’s, as also in Agats. . . . In this Jewel is St. George represented in a riding posture, encount[e]ring the Dragon with his drawn Sword. . . . This George is allowed to be enriched and garnished at the pleasure of him that wears it. [1]

Two historical references of a George incorporating a watch have so far come to light. The first watch appears in the inventory from 1587 of the jewels of Queen Elizabeth I,[2] and the second watch is found in an inventory from 1614 of the possessions of Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton (1540–1614).[3] The George watch in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection is apparently the sole surviving example of this kind of watch.

The Museum’s watchcase, made of gold and decorated with variously colored enamels, consists of an oval band with a pendant and two hinged covers. The front cover has a hinged gold bezel set with an oval plaque of rock crystal. The exterior side of the band has a representation of the garter (or symbol of the order) located between its two beaded borders, and includes the motto: “HONI.SOIT.QVI / MAL.Y.PENSE” (Evil be to him who thinks of it). The beaded borders carry traces of opaque blue enamel en ronde-bosse, or applied to a raised metal surface, as does the sculpted fleur-de-lis-like pendant. The remainder of the band is decorated with champlevé enamel, a technique achieved by cutting away, or excavating, the underlying gold ground so that colored enamels can be applied to the hollowed-out area, fired in a kiln, and subsequently polished down to the level of the gold ground, a process that creates a design in which each color is separated by a gold border that is actually part of the metal band. The colors of the band are translucent blue for the garter, opaque white for the buckle and holes of the garter, and translucent red for the background. The hinged back cover is cast, and its exterior bears an image in relief of Saint George slaying the dragon. These figures are enameled en ronde-bosse on a matte gold ground in white, green, blue, and red. The interior of the cover is decorated with scroll ornament in opaque black champlevé enamel on a stippled gold ground.

The dial is attached to the movement, which can be made to slide into the band of the case, where it is held by two latches that are attached to the back plate of the movement. These latches engage two holes in the band of the case. The dial has four lugs that fit into slots in the band of the case and three feet by which it is pinned to the movement. The back plate of the movement carries the signature of the watchmaker, “N. Vallin.” The decoration of the dial is executed in champlevé enamel with the numerals and half-hour marks in gold on the translucent blue chapter ring. The remainder of the dial is ornamented with scrolls on a background of translucent red. The single sculptured hand is made of gilded brass with traces of black filling.

The maker of the case and dial is unknown, but the George watches found in late sixteenth-century or early seventeenth-century records have been in English possession, hardly surprising since the order is English. It would, therefore, seem likely that the Metropolitan Museum’s watchcase was made in England.[4] A traditional theory holds that this watch is of Continental European origin, which is not implausible.[5] It was not unheard of for English and Scottish watchmakers to make movements for French cases,[6] and until comparatively recent scholarship established the identity of the watchmaker who signed the movement “N. Vallin,” the name could easily have been understood as French.[7] Thanks to the research of H. Alan Lloyd and Charles B. Drover, we have a great deal more information about the maker of the watch than we had before the middle of the twentieth century. Nicholas Vallin (active ca. 1565–1603), the son of Johannes (or John) Vallin (ca. 1535– 1603), was born in the town of Ryssel, Flanders, which is now Lille, France. By 1567, John was in Brussels working as a clockmaker, a move undoubtedly precipitated by the political troubles in the Netherlands, and subsequently he and Nicholas immigrated to London, probably before 1590. Soon thereafter Nicholas became the leading clock- and watchmaker in London, his Flemish training probably responsible for the sophistication of his clocks and watches.[8] Records indicate both he and his father died in the plague epidemic of 1603.

The technological importance of the Metropolitan Museum’s watch lies in its diminutive size.[9] The movement consists of a single train of four wheels, which is driven by a coiled spring regulated by a cone-shaped fusee, and the fusee is connected to the spring barrel by a length of gut. These elements are contained within two oval brass plates that are held apart by four early Egyptian-style pillars, which are riveted to the front plate and pinned to the back plate. When fully wound, the watch has a duration of around fifteen and one-half hours.

The outside of the back plate is engraved with the signature “N. Vallin” with a border of floral scrolls, and includes the head of a putto made in a fashion characteristic of English watches of the late sixteenth century and first quarter of the seventeenth century.[10] The back plate also carries a gilded-brass cock that supports a circular steel balance, a steel click wheel, a brass-nosed steel click, and a click spring for setting up the mainspring (adjusting its initial force). The click wheel, click, and click spring are mounted above the balance, and there are two steel latches for securing the mechanism within the case, one on the left below the foot of the cock, and one on the right above the balance. The cock, click, and latches are richly decorated with pierced work, and the cock is pinned over a stud, or post, which is riveted to the back plate. The steel parts, including the rim of the circular balance, carry traces of gilding.

One of the metal tags that hold the rock crystal cover for the dial is now broken off, and one side of the catch on the back cover of the watch is missing. There are losses of en ronde-bosse enamels on numerous areas of low relief in the scene of Saint George, and the surface of some of the champlevé enamels shows decomposition, especially the areas with blue. Otherwise, the watch is in remarkably good condition. It is not known for whom the watch was originally intended. The inventory that lists a George watch in Queen Elizabeth’s possession is dated 1587, or two years before evidence indicates that Nicholas Vallin was in London. In any case, the description of the queen’s watch does not match that of the watch in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection. The description of the one that belonged to the Earl of Northampton in 1614 is too concise to warrant any conclusion. Furthermore, the earl was not created a Knight of the Garter until 1605, or two years after Vallin’s death. Although two beguiling, though mutually contradictory, theories have been propounded,[11] very little is known of the watch’s provenance before 1857, when it was both illustrated and described as part of the collection of the Englishman Albert Conyngham (1805–1860), who was created first Baron Londesborough in 1850.[12] The watch subsequently came into the hands of Paris antique dealer and collector Frédéric Spitzer (1815–1890), and it is described and illustrated in a volume of his collection catalogue published in 1892.[13] After the auction of his collection in Paris the following year, the watch passed into the collection of Carl H. Marfels, the German watch dealer and collector.[14] Marfels exhibited his collection in Neuchâtel, the Swiss watchmaking city, in 1910, and on that occasion the collection was sold to J. Pierpont Morgan, despite a concerted attempt by local businessmen to keep it in Switzerland.[15] The watch finally entered the Metropolitan Museum’s collection in 1917, as one of Morgan’s many gifts.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] Ashmole 1672, sect. ix, p. 226.

[2] “A book of soche Jewells . . . delivered to the charge and custodie of Mistress Mary Radclyffe,” Ms. Royal Append. 68, British Library, London. Quoted in Britten 1894, p. 61, and Hayward 1969, pp. 2–4, among others.

[3] Shirley 1869; for the watch, see p. 350.

[4] For a discussion of the probable origin of the case, see Leopold and Vincent 2000, pp. 141–43.

[5] Ibid., pp. 145–46.

[6] Ibid., p. 148, n. 12; Vincent 2007, pp. 317–21.

[7] Lloyd and Drover 1955.

[8] For Vallin’s musical clock in the British Museum, London (inv. no. CAI-2139), see Thompson 2004, pp. 56–57.

[9] For further discussion of the effect of size on the technology of the watch, see Leopold and Vincent 2000, pp. 144–45.

[10] Hayward 1969, p. 6, and pls. 1, 2, 5, 7, 9.

[11] See Leopold and Vincent 2000, pp. 145–46.

[12] Fairholt and Wright 1857, p. 80, and pl. xxvi, figs. 6, 6a.

[13] Collection Spitzer 1891–93, vol. 5 (1892; plate vol.), “Horloges et montres,” pl. vii, no. 3; Palustre 1892, p. 53, no. 3.

[14] Speckhart 1904, pl. ii, nos. 1–3. For Marfels, see Marfels 1921; Otto 1929; von Osterhausen 2003. See also Williamson 1912, pp. 136–37, no. 143, and pl. lxiv.

[15] “Morgan’s Collection of Watches” 1913; “Collection of Watches” 1914.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.