Watch and chatelaine

Case maker: Hippolyte Téterger French

Gold of chatelaine chased by Jules-Paul Brateau French

Not on view

During the Nineteenth century in France, a variety of ornament known as grotesque was understood to be a revival of Italian Renaissance design. Derived ultimately from Roman wall decorations discovered during the excavations begun in Rome about 1480 in the Domus Aurea (Golden House) of the emperor Nero (37–68) the style was quickly adopted by Italian artists and soon widely disseminated through the medium of prints.[1]

An etching from a series titled Petits Panneaux Grotesques (1562) by Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau (ca. 1520–1585/86) [2] displays both the vertical organization and the fanciful inhabitants of the grotesque style, which took its name from the grottoes or underground areas where the motifs were originally found. Du Cerceau’s etchings or similar ornament prints must have inspired the designer of a French watch and chatelaine in the Metropolitan’s collection. The object is a product of a Parisian jeweler at work during a period of eclectic taste when a sixteenth- century vocabulary of ornament could comfortably be combined with a watch suspended from an elaborate chatelaine, itself a revival of a fashion current a century earlier than the Museum’s watch and chatelaine.

The watch was illustrated in a report by Lucien Falize (1839–1897) of the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878, which appeared in the influential Gazette des beaux-arts.[3 ]A great deal more is known about Falize than about Hippolyte Téterger (1831–after 1891), the maker of the case and chatelaine. Henri Vever (1854–1942), author of a three-volume history of nineteenth-century French jewelry, had little to say of Téterger other than that after their apprenticeships with the prominent Parisian jeweler Jean-Paul Robin the Elder (1797–1869), Hippolyte and his brother Eugène had hoped to join Robin’s firm. The opportunity never arose, and the two brothers opened their own establishments, sometimes separately and sometimes together.[4] The date of Hippolyte’s birth remained unknown to historians of jewelry until it was discovered in a French police report in 1891.[5] It is still not known when he moved to the address engraved on the Museum’s watch, when he retired, or when he died. Vever illustrated a bracelet in the Art Nouveau style attributed to the “Maison Henri Téterger” that was displayed in the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900.[6] He noted, as well, that a son, Henri, had been trained by Hippolyte, and he seems to imply that Henri was born in 1862.[7] Some later historians have apparently remained uncertain of Vever’s meaning and have assumed that 1862 was the date when Henri took charge of his father’s firm (Maison Téterger).[8 ]The assumption is most unlikely, however, given the age that Hippolyte would have been at the time, to say nothing of Henri. Moreover, Falize,[9] writing in 1878, felt free to describe the Museum’s chatelaine as among the best works of “Monsieur Téterger,” seemingly indicating that at that time Hippolyte was still the only Téterger to be credited with its creation, but in the same sentence crediting Jules Brateau (1844–1923) with chasing the gold elements.[10]

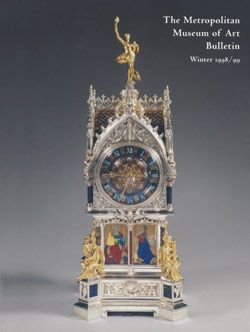

The mythological griffins, the half-human females, and the mask at the bottom of the chatelaine are beautifully executed, but most of the effect of the piece depends upon the setting of the diamonds, which were cleverly chosen to emphasize the separate parts of the design. From the top, the design begins with a three-leaved ornament reminiscent of the French lily, or fleur-de-lis, that grows out of a large diamond flanked by the gold figures of addorsed griffins. The griffins are seated upon a larger diamond that anchors a cascade of diamond-encrusted foliage and is flanked by diamond-petaled flowers from which depend a continuous diamond-set, M-shaped chain. Punctuated by large diamonds, the chain forms the attachment for the raised arms of the two half-nude females, their tails ending in a golden grotesque mask with diamond-set tendrils issuing from its mouth. The diamond-encrusted foliage that hangs below the center of the “M” serves to disguise the hook by which the pendant of the watch can be attached so that either the dial of the watch or the back of its case is visible. A gold tongue-shaped clip with openwork neoclassical ornament derived in part from Greek honeysuckle motifs is attached to the back at the level of the two diamond-petaled flowers and stamped “HIPPTE TETERGER / H. T. DÉPOSE.”

The watchcase displays an exquisite use of enamel combined with gemstones, another greatly admired skill of Téterger’s. The back of the case, the side that would ordinarily be visible when the watch was worn, consists of a large central diamond set within an eight-pointed star and eight spade-shaped ornaments, all set with diamond trefoils on a ground of dark and light blue, pink, and mauve enamel encircled by a band of small diamonds. The back snaps off to reveal the gold dome of the inner case that is signed “Téterger / 31 RUE ST AUGUSTIN / Paris.”

Lest any part of the case appear to have been neglected, the side of the gold case, or band, supports applied foliate designs of platinum set with diamond sparks. The front cover is glass with a bezel set with yet another circle of small diamonds. The glass cover allows a clear view of the dial with its hour circle (1–12) in blue and white enameled Arabic numerals that are separated by gold fleurs-de-lis. The center of the dial consists of a pink and mauve enameled design of quatrefoils issuing from a cluster of foliage, against which the openwork hands with diamond chips set in platinum inspire admiration not only for their exquisite craftsmanship but also for the ease by which the time can be read. The winding stem, too, is pavé-set with tiny diamonds, more diamonds adorn the dolphins that form the pendant of the watch, and yet another cluster of diamond-set foliage is applied to the band at the six o’clock position. Altogether, the object is a prime example of nineteenth-century French extravagance that might be dismissed as mere exhibition showmanship except for the fact that the craftsmanship it displays is exquisite.

The movement is unsigned, but it is a high-quality example of single-plate bridge construction with ruby endstones pivoting the arbors of its three wheels, a lever escapement, and a spring balance with temperature compensation. It features the two steel wheels necessary to wind the mainspring by manipulation of the stem,[11] a commonplace occurrence in Continental watches made in both France and Switzerland by the 1870s. The anonymity of its maker suggests that the prestige of the jeweler far surpassed the reputation of the watchmaker.

A few small diamonds on the chatelaine are missing.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] See Dacos 1969, pp. 78–99; see also entry 2 in this volume.

[2] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (acc. no. 21.10.1[11]), from the Paris edition of 1562.

[3] See Falize 1878, pp. 253–54.

[4] See Vever 1906–8, vol. 1 (1906), p. 208. See also Gere and Rudoe 2010, pp. 286–87, 289, 519, n. 166.

[5] Mémoires de M. le Préfet de la Seine 1892, p. 752, Procès-verbal of Dec. 27, 1891, naming Hippolyte Teterger, born in 1831, a jeweler living at rue des Mathurins, 3. The author thanks Rose Whitehill, former Research Associate, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum, for bringing this information to my attention.

[6] Vever 1906–8, vol. 3 (1908), p. 616. See also Duncan 1994, vol. 2, p. 233, in which the bracelet and a neck ornament, both displayed in the Exposition Universelle in 1900, appear as the work of Henri Teterger.

[7] Vever 1906–8, vol. 3, p. 645.

[8] See, for example, Gere 1998–99, p. 40.

[9] See entry 54 in this volume for more about Falize.

[10] See Falize 1878, p. 254. Jules Brateau is well known for his skill in metalworking. The Museum has seven of his designs in pewter (acc. nos. 1985.110.1, .2, 1992.16.1, .2, 1995.396.1, .2, and 2001.657).

[11] See entry for 1983.183.5 in this volume.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.