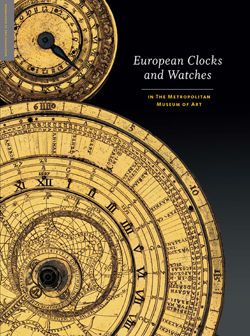

Longcase clock with calendar

Clockmaker: Joseph Knibb British

When the earliest pendulum clocks were made, short pendulums were directly attached to the crown-wheel and verge escapements. These early clocks were subject both to friction in the escapement and to a slight circular error in the pendulum’s swing. Although they were far more accurate than almost all the clocks that had preceded them, they were not ideal timekeepers. While clockmakers tried various solutions, they found that it was sufficient to use a pendulum that swung in a small arc to obtain better results, but this improvement necessitated a new form of escapement. It remained for English clockmakers to develop a practical device that looks somewhat like a ship’s anchor and is controlled by a longer pendulum of approximately thirty-nine inches that beats seconds (the so-called Royal Pendulum). The optimum shape of the anchor was not immediately determined. Several experimental shapes are illustrated by Tom Robinson,[1] and further evidence of early changes in the shape of the anchor can be found in the movement of one of the Metropolitan Museum’s longcase clocks (1999.48.2).[2] Problems with the pendulum that were caused not only by changes in temperature and atmospheric pressure but also by the escapement, which produced a rocking motion of the anchor as it alternately advanced and slightly retarded the teeth of the escape wheel, a motion that created a slight recoil of the wheel. These problems were eventually solved during the course of the next century. Nonetheless, the anchor escapement and long pendulum contributed immensely to the enormous success of English clockmaking.

In the last decade of the seventeenth century, the London clockmaker William Clement (1633–1704) [3] was credited with the invention of the anchor escapement.[4] The priority of the invention had already been disputed by Robert Hooke (1635–1703), Curator of Experiments for the Royal Society of London, but while Hooke is known to have experimented with pendulums, there is little evidence that he attached them to an anchor escapement.[5] Joseph Knibb (1640–1711), however, is now recognized as having fitted an anchor escapement and long pendulum to a turret clock in Wadham College, University of Oxford, in 1670,[6] and he is credited with the conversion in the same year of the clock in the University Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Oxford, to an anchor and long pendulum.[7] Historian C. F. C. Beeson, who did much of the original research on the Knibb family of Oxford, was probably the first to point out that the Wadham College’s clock preceded by one year the clock with an anchor escapement by Clement for King’s College, University of Cambridge, known to have been made in 1671.[8]

Born in Claydon, Oxfordshire, Joseph Knibb was not apprenticed in either Oxford or London. He may perhaps have learned the clockmaking craft in Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire, from his cousin Samuel Knibb (1625–1690).[9] Although he is known to have worked in Oxford, Joseph was not granted freedom of trade there until 1668; instead, he became an employee of the university.[10] By 1663, Samuel had moved to London and paid a fee to become a member of the Clockmakers’ Company. He died in London in 1670, perhaps providing the occasion for Joseph’s subsequent move there.[11] Whatever the circumstances, Joseph was made free of the Clockmakers’ Company in January 1670 (or 1671 in the new calendar),[12] leaving his brother, John, in charge of the Oxford business. Whether or not Joseph Knibb had a claim to the priority of the invention, his longcase clocks, with their anchor escapements and seconds-beating pendulums, assured his success in London, even in competition with such outstanding clockmakers as Thomas Tompion (1639–1713), John Fromanteel (1638–1692), and Daniel Quare (1647/49–1724).

The Metropolitan Museum’s clock exemplifies the variety of longcase clock that made Knibb so successful. The case, developed in response to the improvements in the technology of the pendulum, now had wider proportions than the earliest longcase clocks, allowing the new, seconds-beating, long pendulum to swing undisturbed. The walnut- veneered plinth, with four bun feet that are rare survivals of seventeenth-century casemaking practice, supports a well-proportioned trunk. The trunk, in turn, supports a rising hood that rests on a convex molding typical of English clockcase design before about 1700, and consists of a protective pane of glass for the ten-inch-square dial framed in walnut veneer and flanked by baroque columns with simple Tuscan-style capitals made of carved walnut. The columns support an elegantly proportioned cornice that incorporates a fabric-backed wooden frieze of openwork scrolls. Above, the pediment consists of swan-necked baroque scrolls with floral swags, which frame a central block with a carved wooden cockle shell. Ten panels of matched walnut veneer on the door to the trunk are framed by half-round walnut strips that provide the sole decoration of the lower portion of the case.

The special delight of the exterior of the clock lies in the dial. One of Knibb’s most felicitous, it has a silvered-brass skeleton chapter ring marked with roman numerals (I–XII) for the hours, with each individual minute in Arabic numerals (1–60) on the outer edge of the ring. On the interior edge, the quarters are marked by lines, and the half hours are marked by lozenge-shaped cutouts. The ring is applied to a finely matted area of the gilded-brass dial plate, and the remaining surface is polished and gilded brass with four applied reliefs of winged cherub heads in foliate ornament for the spandrels.[13] The remaining portions of the dial plate are enlivened by engraved foliate scrolls; at the center bottom edge, the clockmaker’s name appears: “Ioseph Knibb London.” A small aperture at the twelve o’clock position reveals the day of the month, and three holes for winding squares complete the dial. The two steel hands are described elsewhere as “hollow cut, bevelled and facetted.”[14]

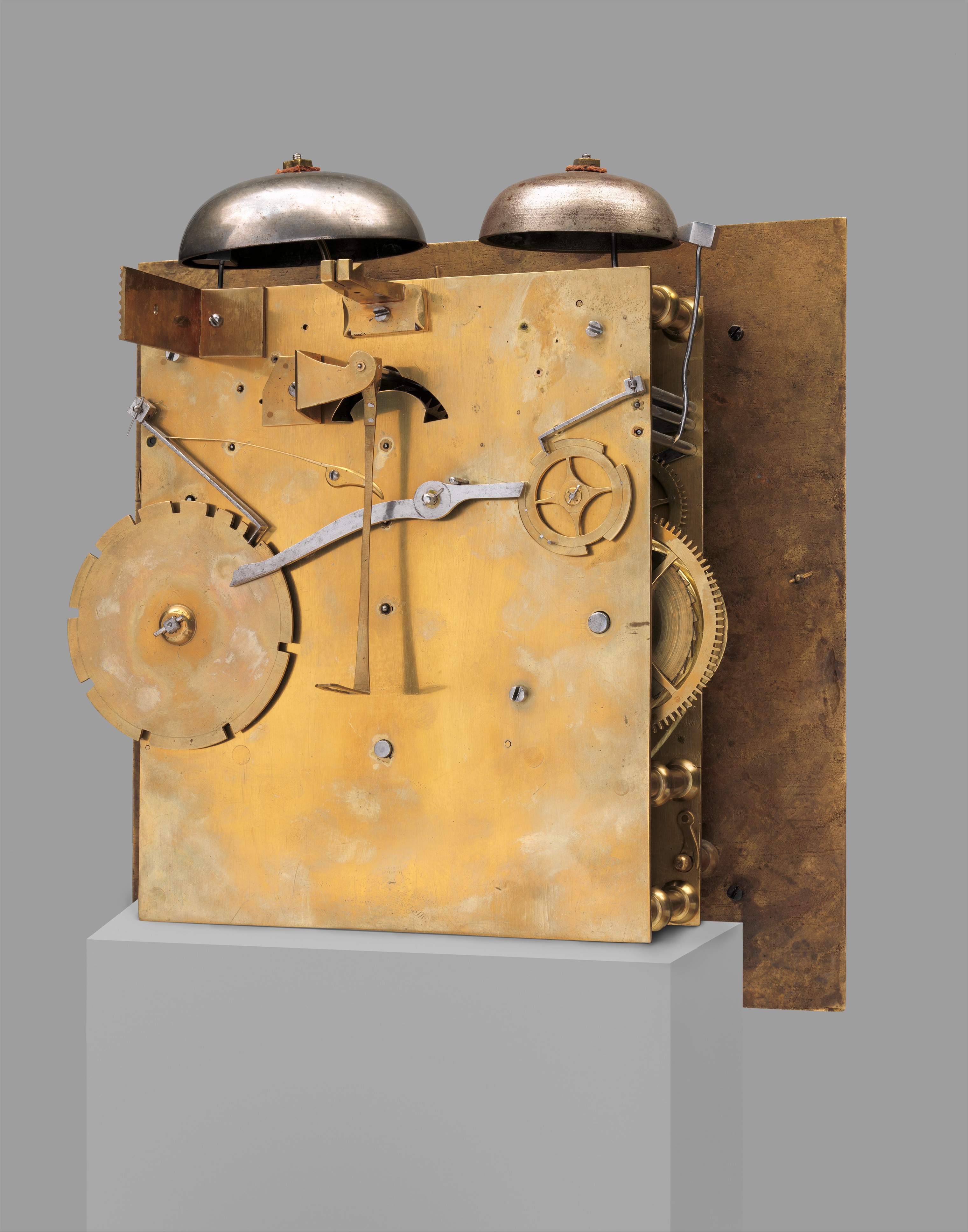

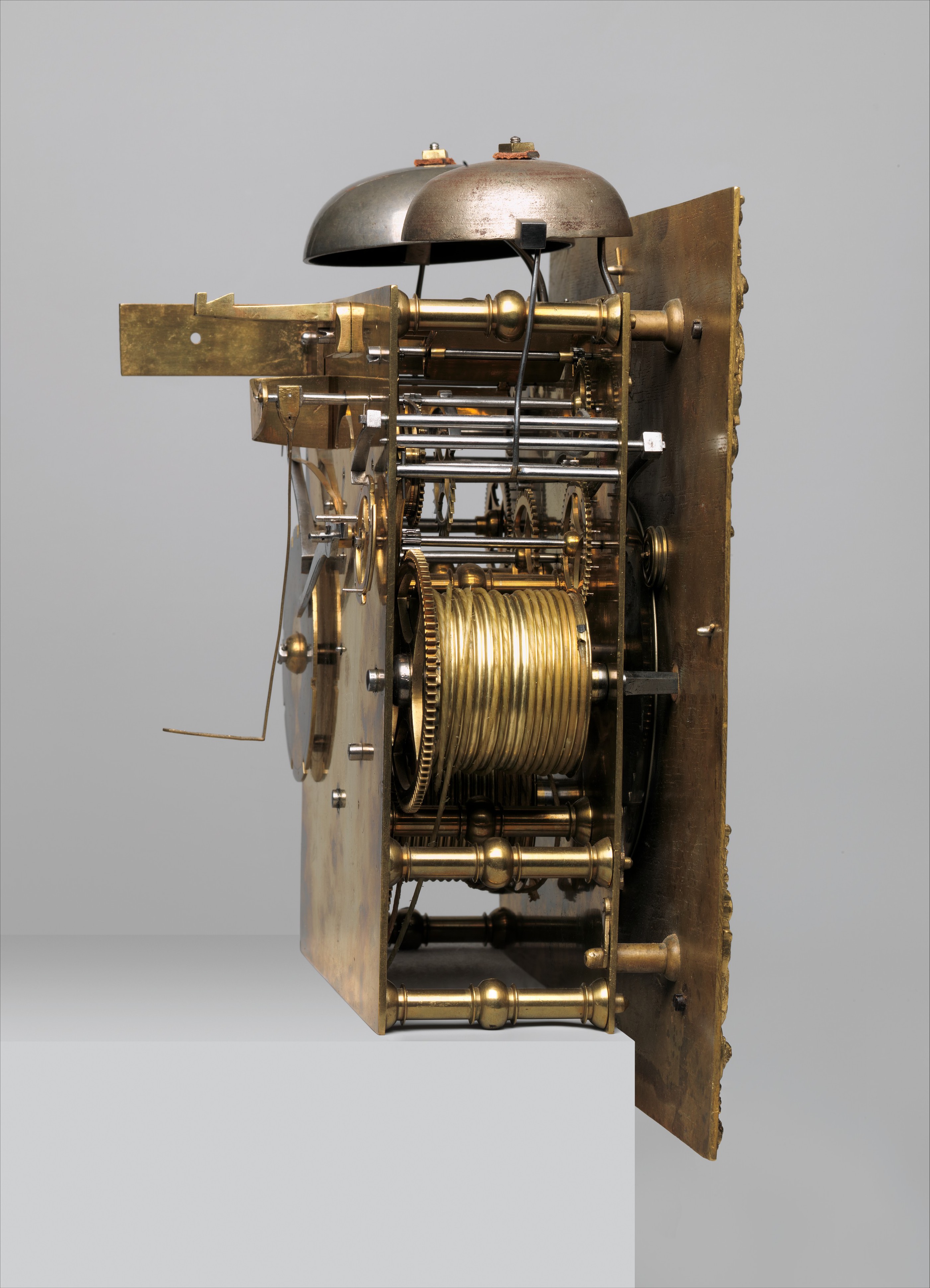

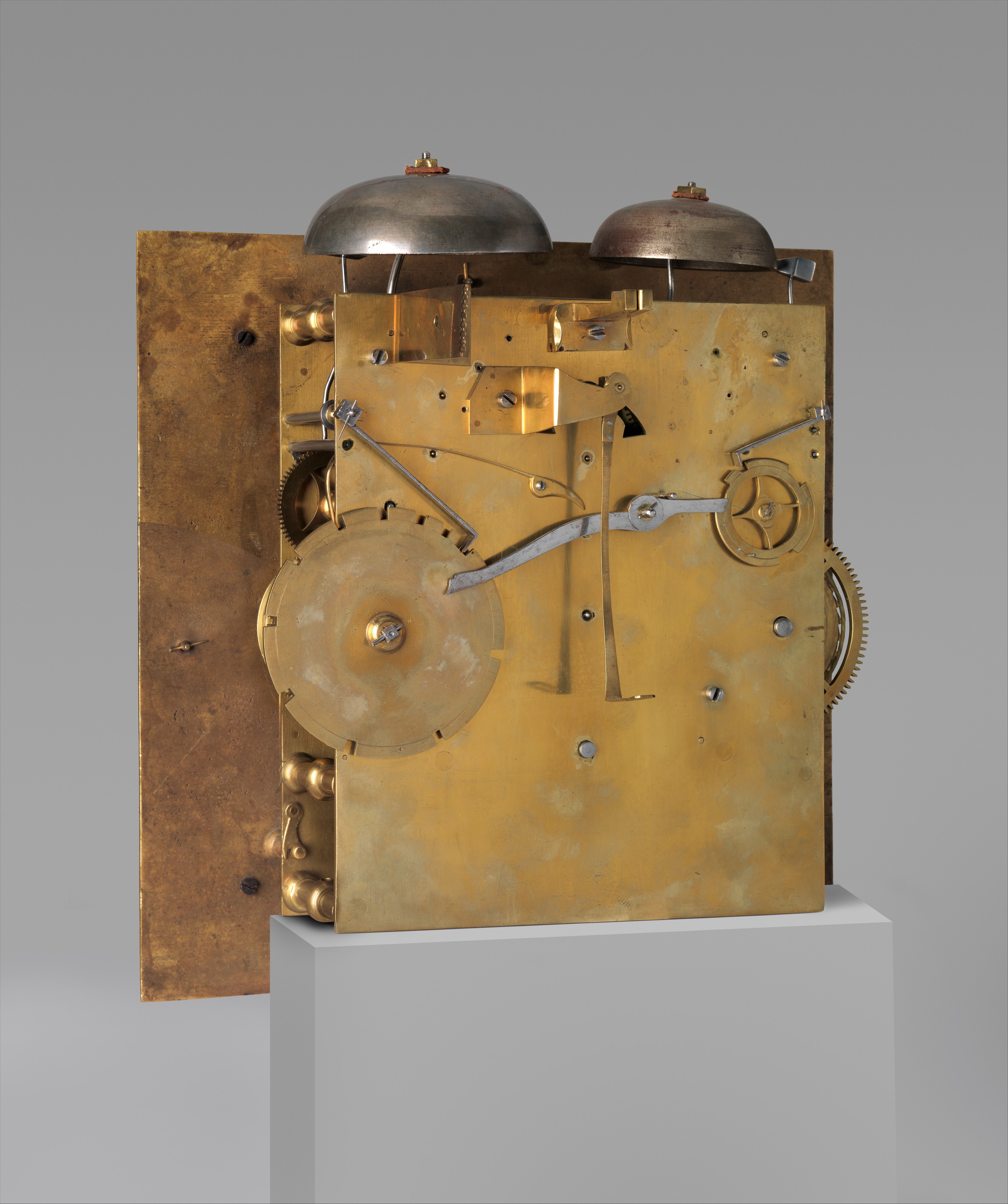

The weight-driven movement of the eight-day duration for this clock consists of a central going train of four wheels that end in an anchor escapement with a long pendulum. Two separate trains for hour striking and quarter-hour striking on two bells occupy the sides. The right side contains the hour-striking train that consists of four wheels and a fly, and the left side contains the quarter-striking train that also consists of four wheels and a fly. The front plate is divided into three latched sections and held apart from the back plate by twelve pillars in a system that greatly facilitates access to a single train, which makes repairs considerably easier for clockmakers. Other features facilitate repairs, including the latches on the interior of the front plate for ease in securing the feet of the dial plate, and the slot in the back plate that allows the removal of the anchor and its arbor without taking apart the entire movement. In the hourstriking train, the great wheel carries the count wheel that governs the number of blows struck by a hammer on the larger bell. The quarter-striking train is powered by a separate weight and has its own count wheel mounted, like the hour-striking count wheel, on the exterior of the back plate. It strikes quarters on the smaller bell. This arrangement makes it easy to adjust the cycle of striking.

Although the movement was made to have a seconds hand, instead it has a calendar for the day of the month in place of a seconds chapter ring. The cock for the pendulum crutch is a replacement, as is the pendulum spring. The small bell is probably not original, and the quarter-striking fly is a replacement. The twisted columns applied to the hood may at one time have been blackened. Irwin Untermyer purchased the clock from a London auction,[15] and the accompanying catalogue states that it had been the property of one religious institution since the eighteenth century, though the name of the institution has not been disclosed. The clock was in running condition when it entered the Museum, and it has been running more or less continuously since 1975.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] Robinson 1981, p. 45, figs. 3/1, 3/2.

[2] See entry 22 in this volume.

[3] Loomes 1981, pp. 151–53. See also Penfold 1962.

[4] J. Smith 1694 and Derham 1696, quoted in Robinson 1981, p. 44.

[5] For further remarks about Hooke, see entry 23 in this volume. See also Hall 1978, p. 263.

[6] See Beeson 1967, pp. 64–66, and pl. 5, figs. 7, 8. The clock is now in the Science Museum, London.

[7 ]Ibid., pp. 61–62.

[8] Ibid., p. 66. See also Thompson 2004, p. 76; Vehmeyer 2004, vol. 2, pp. 503–5.

[9] Beeson 1967, pp. 122–23. Lee 1964, pp. 14–15, gives a slightly different account.

[10] Beeson 1967, p. 122.

[11] Ibid., pp. 124–25.

[12] Ibid., p. 123; Loomes 1981, p. 343.

[13] See Robinson 1981, p. 449, fig. G/6, no. 5, said by the author to have been rarely used before about 1685.

[14] Lee 1964, p. 97, said by Lee to be typical of those used by Knibb for longcase clocks between 1680 and 1695.

[15] Christie’s 1972, p. 13, no. 17, ill.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.