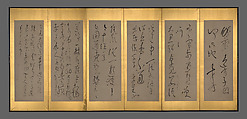

Screens with Chinese Poems

Ryōkan Taigu Japanese

Not on view

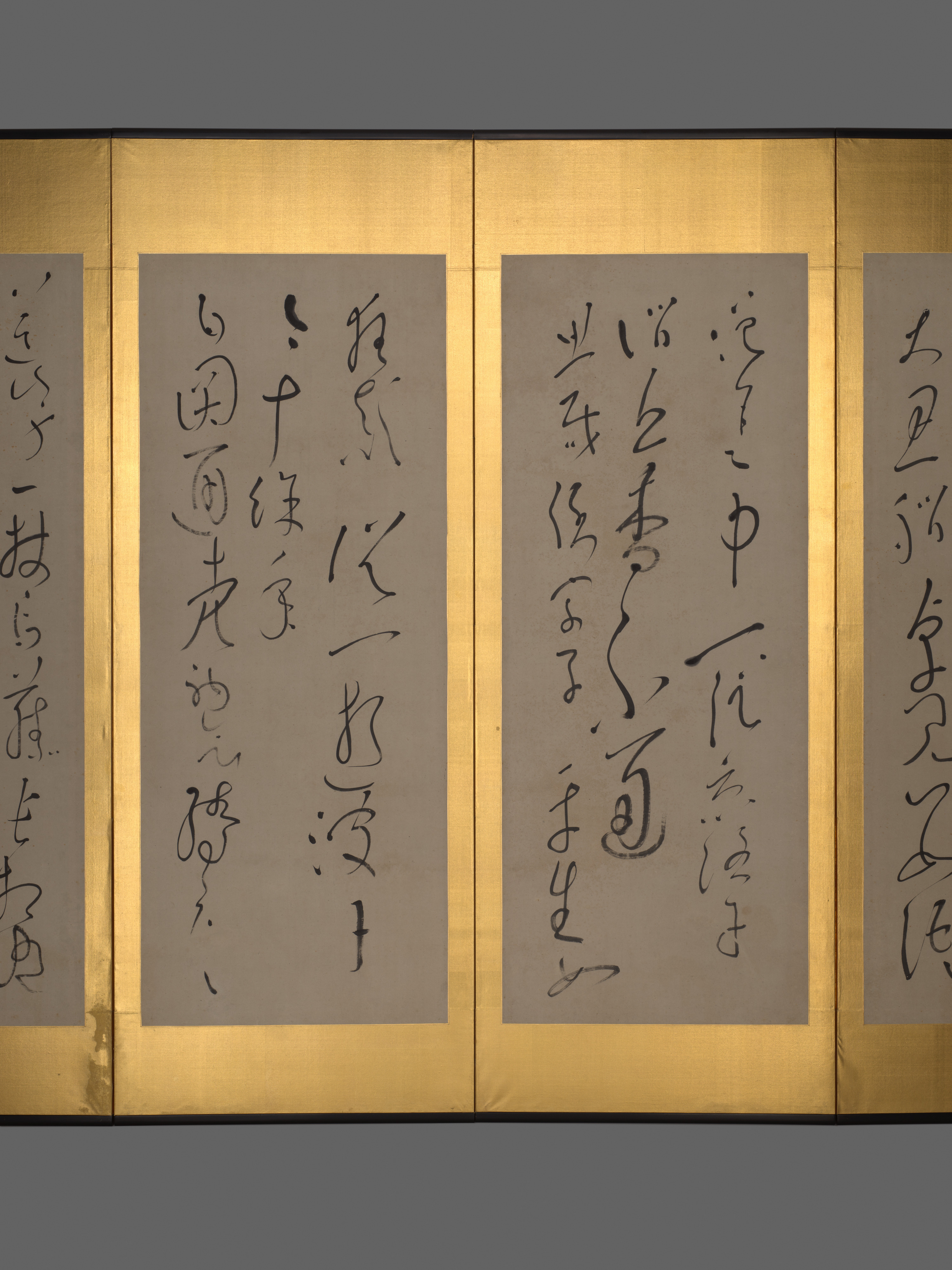

Ryōkan Taigu studied model books of Japanese and Chinese brush writing in cursive script. The script’s simplified forms, abbreviating the rigid structures of characters through fluid curvatures, became prevalent in his calligraphies, which he executed with a thin brush to emphasize the liberated shapes of the characters.

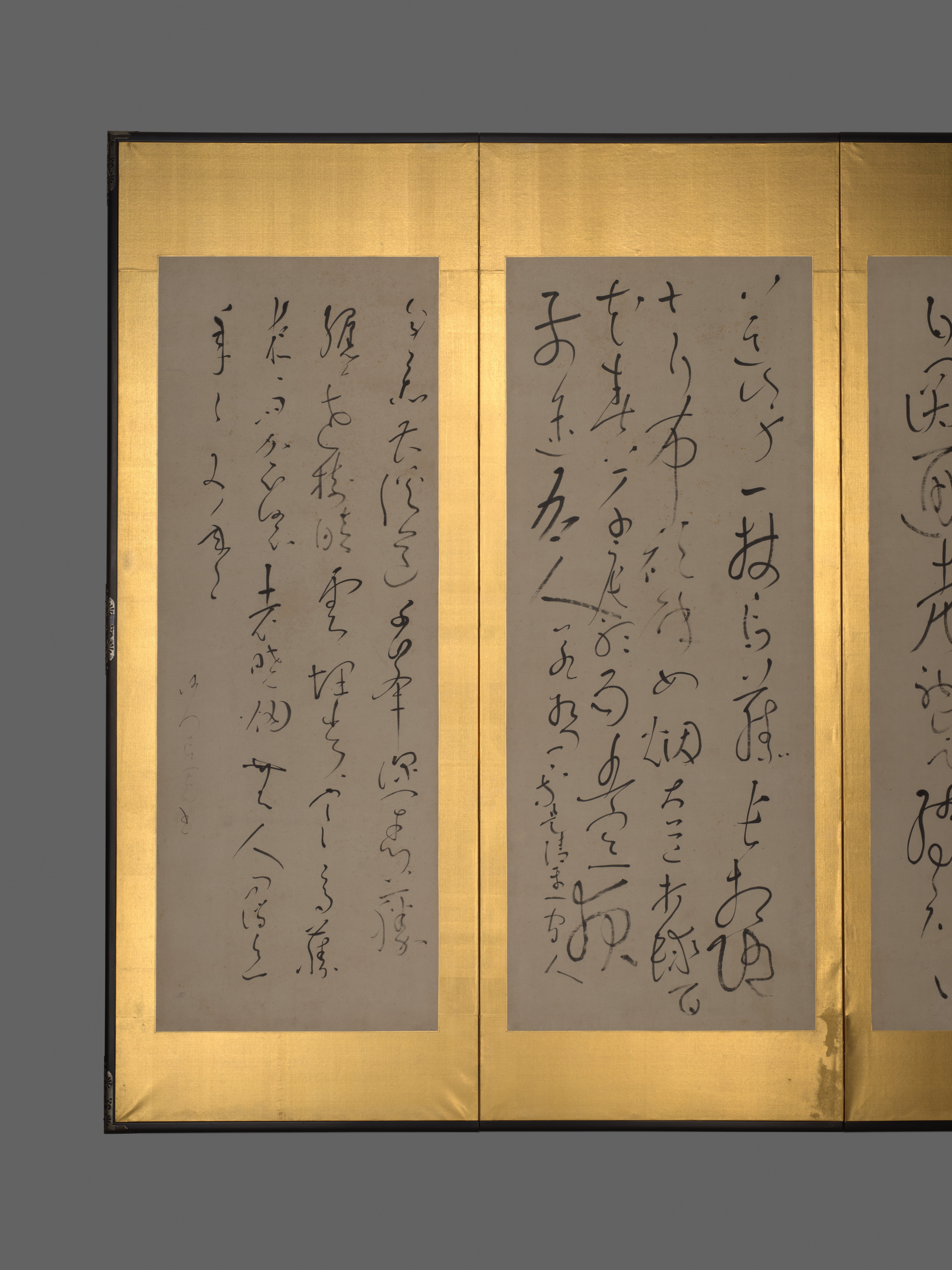

The opening poem on the left-hand screen reveals that, for Ryōkan, calligraphy was a means of pursuing Buddhist teachings. It reads:

吾与筆硯有何緣 一回書了又一回

不知此事問[阿]誰 大雄調御天人師

What karmic bond draws me

to the brush and inkstone?

Once I have written, I write yet again.

I know not whom to ask about this matter,

the Buddha, the Great Mentor,

the Teacher of Gods and Men.

In this pair of screens, twelve individual sheets are mounted within borders of gold-painted paper that has been pressed to resemble the texture of silk. The Sōtō Zen monk Ryōkan Taigu transcribed nine original Chinese poems in his unrestrained cursive style. Instead of a conventional composition, with characters of similar size aligned in columns, Ryōkan opted for a haphazard arrangement of variably spaced and scaled characters.

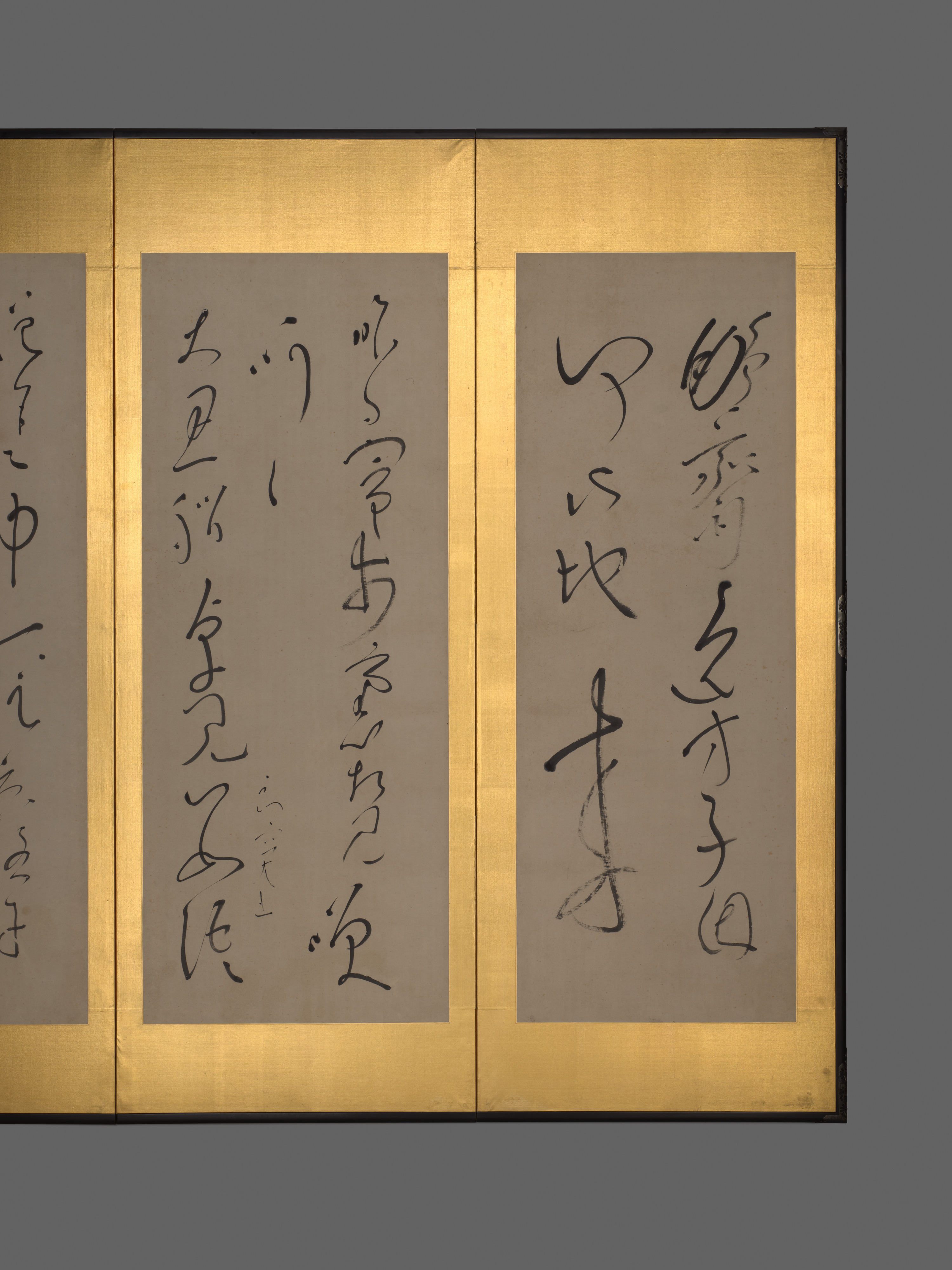

The first poem describes an unexpected encounter with his literati friend Kameda Bōsai (1752–1826), a calligrapher also renowned for his idiosyncratic cursive script:

鵬齋逸才子 因何此地來

昨日鬧市裏 相見咲呵々

Bosai, the unfettered genius,

why has he come to this place?

Yesterday in the bustling marketplace

we met and laughed with joy.

The opening poem on the left-hand screen reveals that, for Ryōkan, calligraphy was a means of pursuing Buddhist teachings. It reads:

吾与筆硯有何緣 一回書了又一回

不知此事問[阿]誰 大雄調御天人師

What karmic bond draws me

to the brush and inkstone?

Once I have written, I write yet again.

I know not whom to ask about this matter,

the Buddha, the Great Mentor,

the Teacher of Gods and Men.

—Trans. Tim T. Zhang

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.