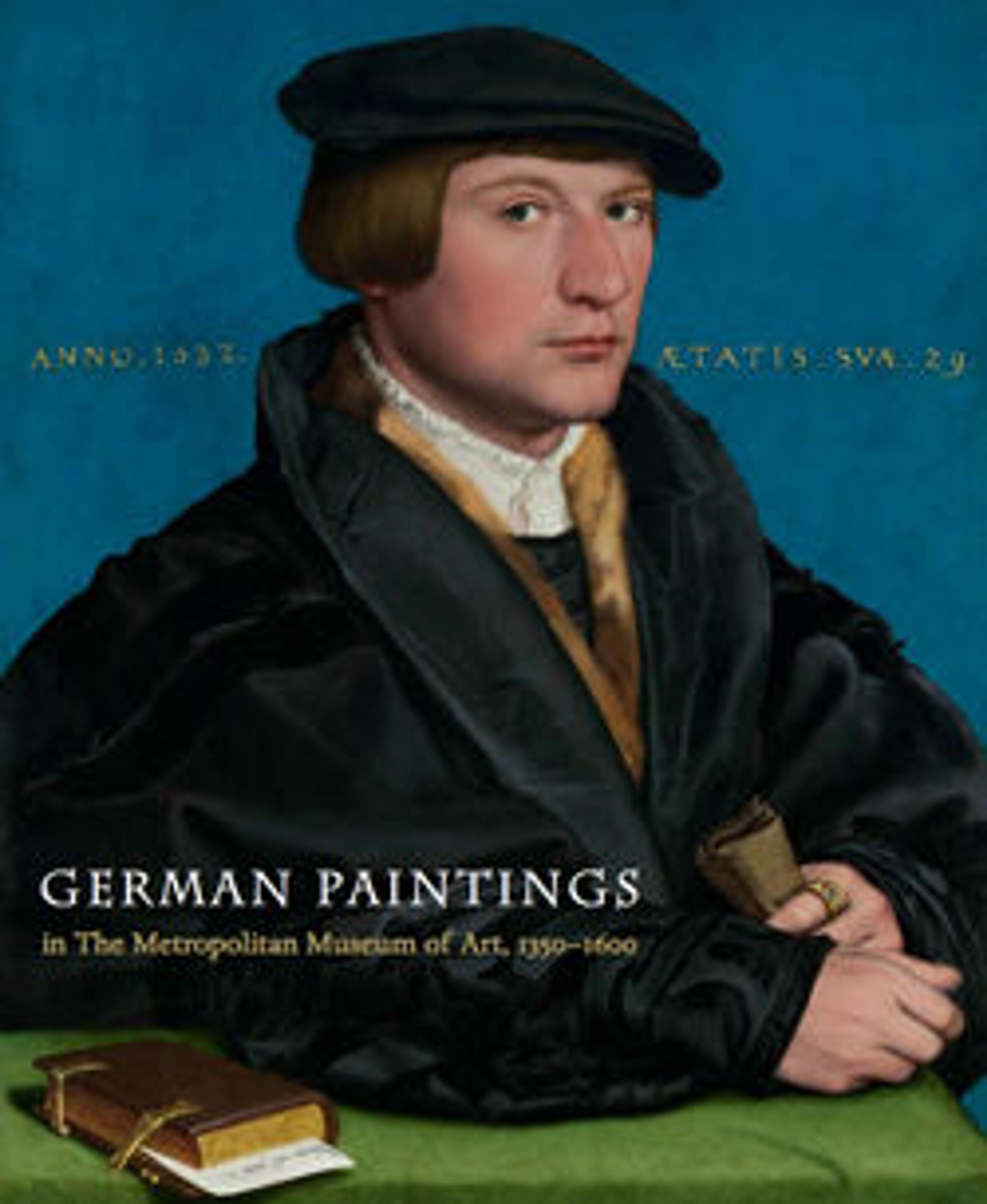

Benedikt von Hertenstein (born about 1495, died 1522)

In 1517 Holbein decorated the house of Jakob von Hertenstein, a magistrate in the Swiss city of Lucerne. At the same time, he made this portrait of the magistrate’s eldest son, Benedikt, who engages the viewer both with his direct glance and the inscription in his own voice, which reads: "When I looked like this, I was twenty-two years old." Following these words is the declaration that "HH" painted the work. The artist’s use of paper mounted on wood reflects his working method. He initiated the portrait as a drawing on paper and then continued working it up in oil colors to its completion.

Artwork Details

- Title: Benedikt von Hertenstein (born about 1495, died 1522)

- Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger (German, Augsburg 1497/98–1543 London)

- Date: 1517

- Medium: Oil and gold on paper, laid down on wood

- Dimensions: Overall 20 1/2 x 15 in. (52.4 x 38.1 cm); painted surface 20 3/8 x 14 5/8 in. (51.4 x 37.1 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, aided by subscribers, 1906

- Object Number: 06.1038

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.