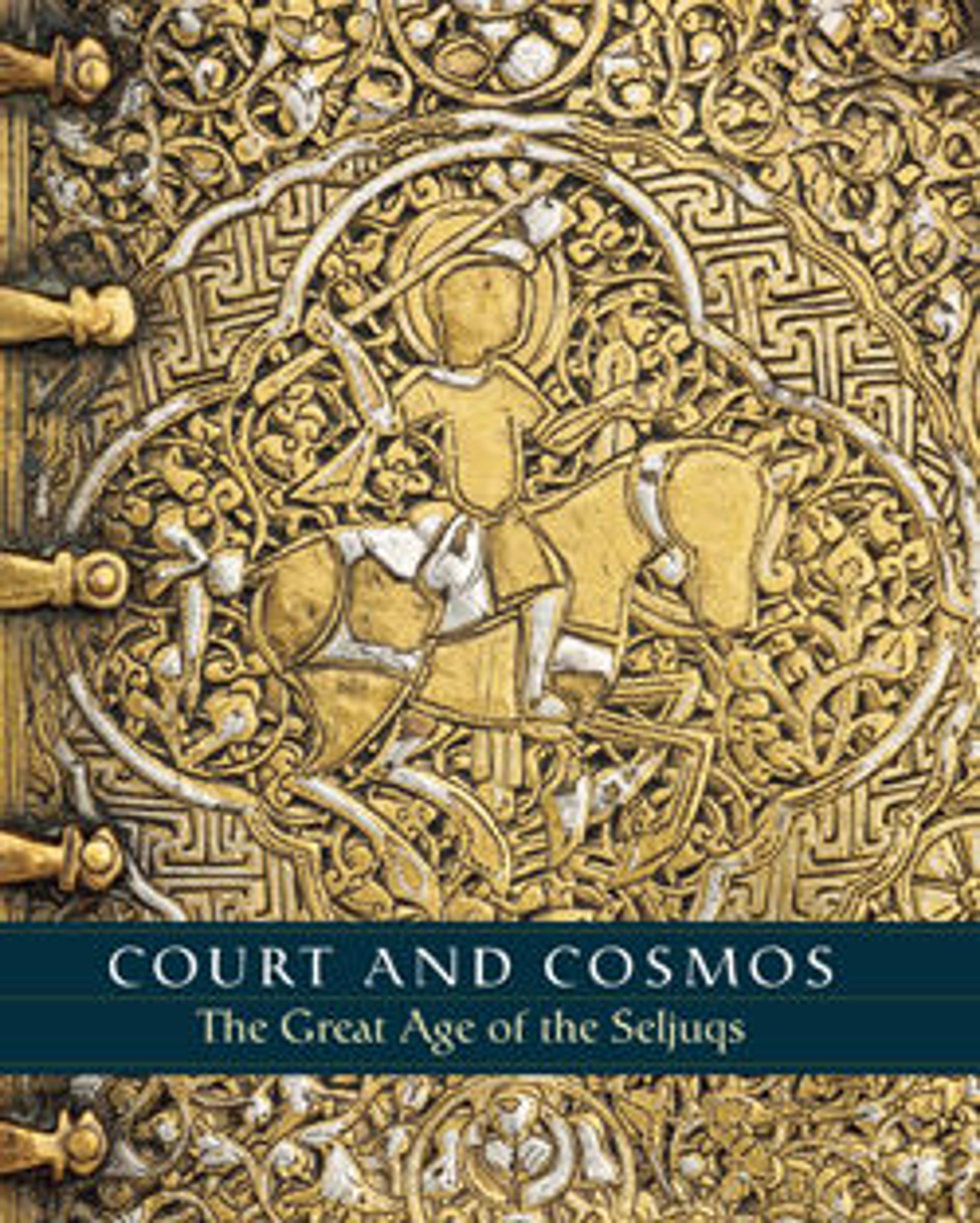

Luster Star-Shaped Tile

Although the technology is believed to have originated in Iraq in the early ninth century and first spread westward to Egypt and Syria, lusterware became a dominant type of ceramic production in medieval Iran, possibly having spread from Egypt to Iran in the early 12th century by artisans migrating to set up workshops. Within Iran the town of Kashan was the finest and most prolific producer of lusterware. One aspect that sets Iranian lusterwares apart from their western Islamic counterparts is the remarkable frequency with which these pieces were accompanied by signatures and dates of manufacture. On the tile presented here, a depiction of a sultan surrounded by members of the court is framed by three quatrains of Persian poetry and dated to the year A.H. 608 (A.D. 1211–12). The leopard and birds may imply that the scene is set outdoors

Artwork Details

- Title: Luster Star-Shaped Tile

- Date: dated 608 AH/1211–12 CE

- Geography: Attributed to Iran, Kashan

- Medium: Stonepaste; luster-painted on opaque glaze with inglaze painting

- Dimensions: H. 3/4 in. (1.9 cm)

Gr. Diam.12 3/4 in. (32.1 cm) - Classification: Ceramics-Tiles

- Credit Line: H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Horace Havemeyer, 1940

- Object Number: 40.181.1

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.