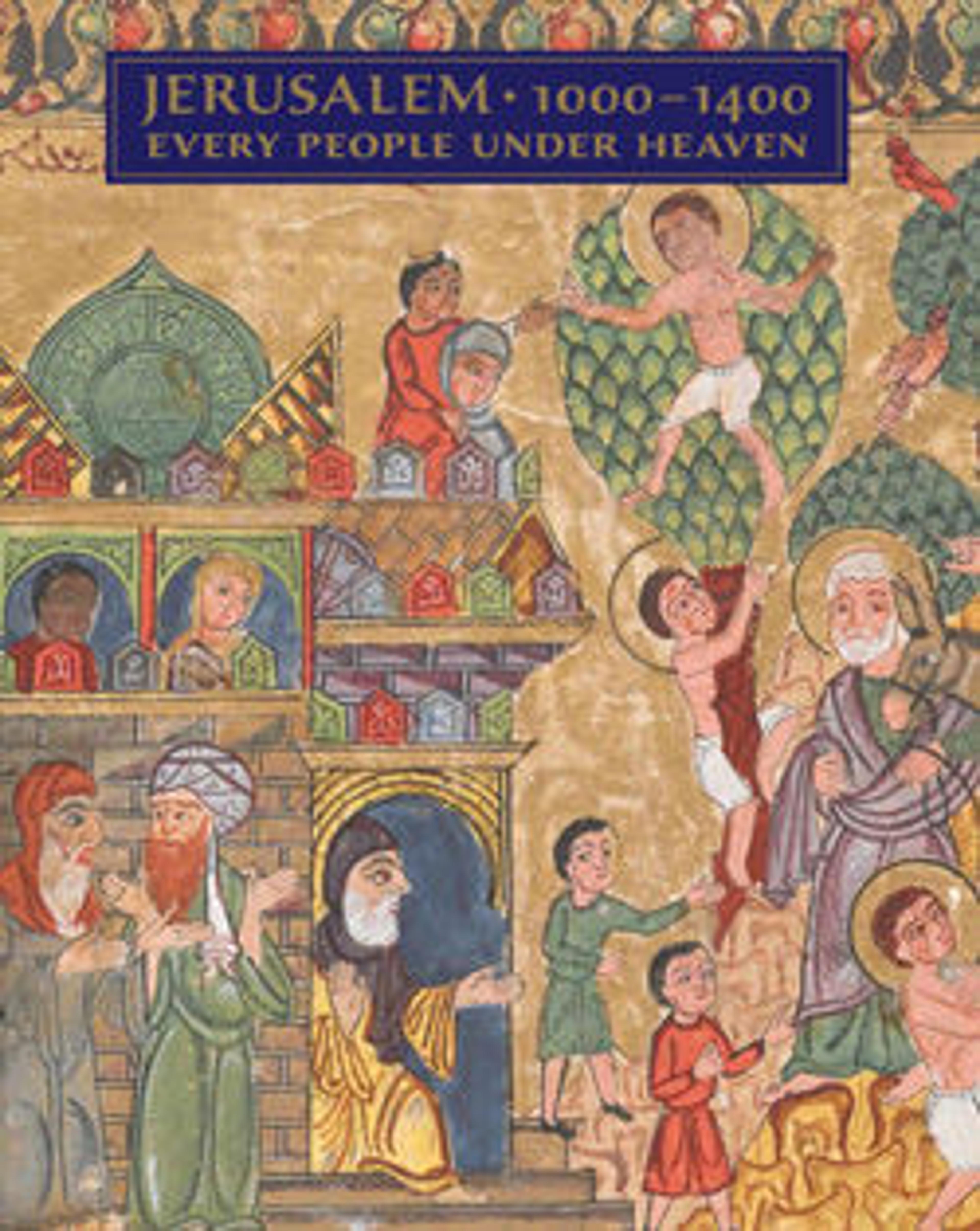

Battle Scene

This scene depicts a battle in which the central figure appears to be the only one who has not lost a limb. Severed heads, arms, and legs and a man who has lost his hand are arranged across the composition. The legs and tail of a downed horse are visible at the lower left. The sketchy drawing and thin wash used for the figures suggest that the image was produced in thirteenth-century Egypt. The curved swords are associated with "Saracens", as found in a thirteenth-century European illustration of a Crusader battle.

Artwork Details

- Title: Battle Scene

- Date: 13th century

- Geography: Attributed to Probably Egypt

- Medium: Opaque watercolor on paper

- Dimensions: H. 5 1/2 in. (14 cm)

W. 7 3/16 in. (18.3 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Jerome A. Straka Gift, Fletcher Fund and Margaret Mushekian Gift, 1975

- Object Number: 1975.360

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.